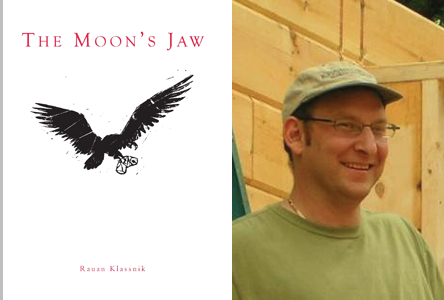

Rauan Klassnik was born in Johannesburg, South Africa and moved to the United States when he was thirteen. For many years he traded collectibles, cards, beanie babies, and the like. He then spent many important years in Mexico and now lives in Kirkland, Washington, with his wife Edith. He is the author of Holy Land, also published by Black Ocean, and the chapbooks Ringing (Kitchen Press) and The Sea (Mud Luscious Press).

Monkeybicycle: One of the most noticeable aspects of The Moon’s Jaw is its insistent collision of violence and sex: “Under the moon’s tightening wrists—Leaning down to pet yr dog, you looked up at me, & shot the dog in its face. We fucked. & we fucked again. & when I came to you were sucking me off.” Where does this come from, and what was it like to focus on two such intense actions for the duration of a full-length project?

Rauan Klassnik: “Where does this come from?”—The world (and life, the universe) is at its core, basically, fueled by sex and violence. So I’d say “this” comes from inside and outside. That it comes quite naturally.

“What was it like to focus on two such intense actions for the duration of a full-length project?”—It felt like dying and being healed, resurrected, over and over, sometimes in pain, and sometimes with pleasure. And sometimes both. It was prayer and plague, and, to a certain extent, what it must have been like for Guyotat during his intense masturbation-writing years. I didn’t quite nearly die though. (No coma). No. Not quite. And, hey, I got to be, gratefully, a bad Caesar. A Caligula. Or a Nero. Ore more so I guess a Tiberius. Aged. And jaded. Sad too. But nonetheless cruel, sexual, sadistic and masochistic. An old man standing up on a balcony watching and masturbating. A grey bullshit torch in the dark.

Mb: The Moon’s Jaw also focuses much of its energy on nature, particularized as a chaotic, vapid, nearly apocalyptic landscape: “The stars glimmer like small blurred-red flowers—& lying next to you, she presses a talon against her clitoris . . . Swollen, like fire . . . & rips up . . . Thru her navel.” Does this stem from the “hot, humid Mexican summer” where the erasure-based raw material was generated, or does it come from elsewhere in your experience or psyche?

RK: My heated love-hate relationship with the universe has swung back and forth through degrees of intensity and stability. This book, though, was created and shaped during an extreme period of dissatisfaction, bitterness, melancholy and fatigue. Erasure then, by its very nature, appealed to me. And, then, close on those heels, my reading of Holocaust Literature (especially Borowski) struck a big, sad and mad gong in me. And I gravitated more and more decadently and selfishly into a personal-imagination wasteland.

And, yes certainly, the heat, oppression, arrogance and blur of a Mexican rainy season (the summer) seasoned things further.

Mb: Over at HTMLGIANT, Ken Baumann said “I read The Moon’s Jaw by Rauan Klassnik and first felt pissed and then I read harder and now I can’t get the book out of my head. It’s a hard book to read, structurally—a lot of dashes and forced spaces in the music of it. But once I accepted them, didn’t try to crush the words together/eliminate the aural space, the images made more sense with the forced cushions.” What do you think of this description of your work?

RK: First of all I think I’d like to kill Ken Baumann (yawn…sigh). But, seriously, I appreciate and agree with what Ken’s saying. I can understand this sort of conflicted, confused and even angry reaction in a reader. And I’m glad that Ken stuck with it and “accepted” because, yeah, I think, also, that the “forced cushions” are important.

And here, as further response, I’d like to quote a piece from the book’s middle section (the section titled “The Great Poet”:

—Into A Skull—You Can Fight It—Or Be My Slave—

—Primitive—Dark & Bony—Spewing Religion—Gasping—

—Inside Of Me—The Core Of Me—Epileptic Unfurled—

—Guts Ripped Swans—Bulls Blood—Light—

At the end of the day I want the book, in a really warped and genuine way, to be kind of a religious experience.

Mb: In terms of the rhythm Baumann highlights, you do use a heavy combination of dashes and ellipses in The Moon’s Jaw. How do you intend the reader to approach each of those symbolic pauses or structural formats?

RK: I want (or is “expect” a better word here?) the reader to have to struggle at least a bit with my book, to feel him- or herself being pushed and pulled. Pushed to read through and mostly dismiss the pesky and insistent punctuation and typography. (Pesky mosquitoes, for example, should be avoided, because they lead to Malaria?). And pulled and dragged back by those same things (they should enjoy the bites?).

The rhythm and flow of the book (on both local and general levels) stagnates, streams forward smoothly, bogs down, etc.,… Like it’s kind of healthy but, also, kind of diseased. And that’s how I wanted it to be. The way it had to be. Could only be. And, to realize this effect, competing impulses came into play. One impulse was to scar the text, both aurally and visually. Scar it blatantly and with great exaggeration. But sometimes this impulse really got out of hand. Became rampant, a disease that the rhythms and energies of the book fed into and off of. (it certainly gave me much delight but also fucked me up.) The other impulse was to beautify, to ornament—like a Monk decorating, with great love, some sacred document up alone in some cold black stone tower. And there were control issues with this impulse also.

All in all, sometimes, it was like struggling with a disease. And I didn’t quite always win. This, though, all being said, I expect and hope that the reader will come to it in good faith.

Mb: Bones, broken and otherwise, appear throughout these poems, which is super interesting imagery given that our bones are at once our core structure, our crux, but also only truly visible when we are split open or decayed. What do bones mean for you as a writer, particularly in The Moon’s Jaw?

RK: Starting with the moon’s jaw(bone?) hanging scraped up in the sky I do seem to have the action of this book, I guess, take place under and within bones. In a world boiled down to its bones. Its primary colors. Or, further even, into Auschwitz ash. And yet, still, the bones are grinding each other, awkwardly, hopefully andd helplessly (like much Literature or like “making love” in a 69 position) in this ruined and bone-thorny landscape.

I don’t think I’m fascinated with bones in particular though (no more so, let’s say, than blood or semen—both of which insistently and recurrently flare and bloom and boom through the book), but certainly bones do come with the terrain. The book’s cemetery-rife, boiled-off skin: bone-white-gleaming marble.

It’s kitschy of word. A trendy word, “Kitsch,” which cuts both ways.

Purchase a copy of The Moon’s Jaw here, view the trailer for the book here, & read more from / about Rauan Klassnik here.

J. A. Tyler is the author of nine novel(la)s of poetic fiction. His work has been published in Black Warrior Review, Redivider, Cream City Review, Diagram, Fairy Tale Review, Columbia Poetry Review, and New York Tyrant. He also runs Mud Luscious Press.