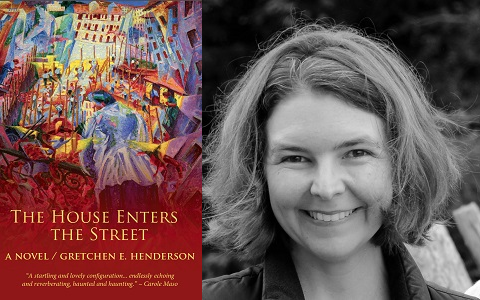

Gretchen E. Henderson writes across genres and the arts to invigorate her creative and critical practices. Her books include two novels, The House Enters the Street (Starcherone Books, 2012) and Galerie de Difformité (&NOW Books, 2011, a book collaboratively deforming across media), along with collections of nonfiction and poetry, On Marvellous Things Heard (Green Lantern Press, 2011) and Wreckage: By Land & By Sea (Dancing Girl Press, 2011). Among other awards, she has received the Madeleine Plonsker Emerging Writer’s Prize and Mellon Postdoctoral Fellowship from MIT. Her work has appeared in many literary journals, anthologies, and more unexpected venues (including balloons, blenders, and beehives).

The docent looks directly at Avra. And she smiles. It’s the kind of smile out of place with her decorum in the gallery. “I’d like to finish here,” she says to the man and to Avra, “with the Noise of the Street Enters the House. Although I don’t care much for the Futurism Movement, I do appreciate its movement; and I almost hear something when I look at this painting. It makes me wonder what might be created by extension, using today’s milieu, as we understand more and more how movement itself – our ability to move – the movements that make us and that we make, restructure our consciousness….”

Monkeybicycle: The novel is full of the arts, whether they be paintings, music, or dance. What is the role of different mediums on your own art?

Gretchen Henderson: Thank you for sensing the ranging arts in the novel, also for considering writing as an art. Language is a malleable medium, alive and dynamic, constantly changing through usage patterns and contexts. Different art forms remind me that words shift as shapes, resonances, gestures. Genres, too. They have plasticity and performativity, even choreographed silences, with deep histories that disavow strict borders and conventions. It helps to excavate artistic archeologies and trace genre genealogies, which are richly ranging and have intersected with other arts (for instance, lyric poetry arising with the lyre). Each art form has its own repertoire of techniques acquired over history to hone a reader’s or viewer’s or listener’s attentions. Techniques like plot pull a story forward, while images and sounds constellate and echo, suggesting a more three-dimensional shape. Although a text may appear visually linear on a two-dimensional page, sentences may orchestrate a different momentum from plot alone, where a reader can coordinate images, sounds, senses, pauses.

Before writing, I was involved in other arts, particularly music, so aural sensibilities enliven my relationship with language. Visual arts often work in wordless ways that provoke questions about interrelated form and content. I continually appeal to other arts to broaden my sense of what stories, poems, essays, and other writings have been and might be. What are we habituated to reading or seeing or hearing or sensing? How do cultural classifications affect our relationships with writings? How do we (un)write our structures to enable inquiries within and beyond traditional forms? How do we (de)classify to remain open to alternative ways of interpretation, telling, shaping, sharing? Beyond my own projects, collaborations with different artists (whether a composer or installation artist or dancer or book artist or architect or scientist) have invited me to think through and practice language in different media and disciplinary contexts, stirring up more questions about form and content, especially when I return to the two-dimensional space of the page. One of my current projects is an opera libretto, shaping the overall narrative and sequencing pieces for sung voices: a fascinating experience of imagining words into a three-dimensional, performed space. Engaging with other art forms constantly retunes my attentions and appreciations to ways that different artists are investigating sympathetic questions through different materials. As artists, we tend to gravitate to a home medium, and for me, it comes back to words, tethered to the arts.

Mb: In addition to the mixing and blending of arts, the narrative is a complex interweaving of people from across the world trying to sort out their lives. It’s almost a fairy tale, at times, with each part of the novel in dialogue with itself, as it redefines its own narrative. How do stories and art allow us to define our lives, and the lives around us? How important is that?

GH: I love that you found The House Enters the Street as a kind of “dialogue with itself, as it redefines its own narrative.” The novel is structured as a modulating, polyvocal experience to invite multiplicity, as it tries to dismantle expectations for a singular type of storytelling, while attempting to maintain the integrity of the stories within – more, between – the lines. The novel is a performance (in two acts with an intermission) as the narrative modulates through echoing retellings. The namesake painting (Umberto Boccioni’s La Strada Entra Nella Casa) is variedly translated as The Street Enters the House or The Noise of the Street Enters the House, and the element of “noise” is certainly a character/istic of the novel. Much of it boils down to listening. I am interested in acoustic spaces where resonances and rhythms help to shape stories, where interruptions and juxtapositions hone our listening, moving center to margin and margin to center, inviting different perspectives to cohabit and pulse.

Your question about stories seems connected to a basic philosophical inquiry: Why are we here? I can barely fathom! But stories seem to offer points of connection and exchange. We are a storytelling species and tend to explain our lives in terms of stories. Personal stories, professional stories, political or social or cultural or environmental or spiritual or scientific stories, and more. We identify causes and effects, honing in on reference points that help us explain our place in the world, using languages whose structures and roots carry different priorities. Sometimes stories connect us; sometimes their underlying cosmologies (for lack of a better term) collide. Although time might seem forward-bearing, life isn’t experienced as a neat linear narrative, more like a garden of forking paths, mixing choices with accidents, will and chance, memories and dreams, experience and imagination, setting up different experiences and expectations for living in the world, time and space. Reference points change, supporting or challenging traditions and tropes. Stories can carry power, giving rise to the adage of the pen and the sword. Stories can free, as well as constrict, if they stay fixed, discouraged, censored. As we interact, as different mediums carry our stories, as new words enter our vocabularies, as knowledge systems shift, as we evolve with the planet: these multiplicities affect the shapes of our stories, poems, essays, dramas, more. Readings of the changing world shift not only what gets told but also how, and by who, so new stories come into being – or more often than not, old stories appear new in modernized guises. (How many ways to tell a love story!)

Before long, they began to realize that words offered worlds found in The Source that sat fat on a shelf in the classroom, with blue bindings and gilded leaves. From that, they learned that their cloaked guardians wore a mode of behavior that becomes involuntary through repetition. The twins made up meanings for prayers and my-stories, after being taught recitations. They also developed their own incantations, to Holde, to Faar and to Mor: chantable words they had learned before and connected with their yesterdays.

Mb: The House Enters the Street is, I think, the first novel I’ve read where a main character is dealing with a disability, and you study disability studies. What is the draw of disability for you?

GH: There’s a great deal of disability literature that you may have read but not recognized as such, since disabled characters historically have tended to bear symbolic burdens (for instance, correlating external and internal “crippling,” ranging from corrupted Oedipus, to vengeful Captain Ahab, to pathetic Tiny Tim). These representations often connoted disabled bodies as limited, deficient, negative, negligible. There’s a richly ranging and growing body of disability literature, art, and scholarship that works to counter and complicate reductive readings, alongside a more generous and generative sense of “somatic engagements” (to borrow a term of Petra Kuppers). To answer your question, I wasn’t drawn to disability; rather, it found me through personal experience 14 years ago. Physically, I have learned many navigational and adaptive strategies that have influenced the ways that I engage with environments, from buildings to books to technology, even writing. Thinking beyond difficulties in my own small experience, it’s forced me to think about my inherited sense of story and space, not to mention larger cultural questions: Is a body disabling or its context? What are the implications of trying to function within “normal” categories and practices, to perpetuate a rhetoric of limitation rather than potential? What about tapping alternative knowledges to reimagine and redefine boundaries and structures themselves? According to David Mitchell and Sharon Snyder, the problem of narrative harks back to antiquity to what they call “narrative prostheses,” or the “notion that all narratives operate out of a desire to compensate for a limitation or to reign in excessiveness.” This is more than a hypothetical exercise. Rethinking our practices, narratives, environments, and more can open up our imaginations to be open to wider ways of living, being, making, and connecting in the world. (As aside, we don’t always recognize knowledges that arise from disability; as one example, many technologies now considered mainstream and popular – like the multi-touch screens and voice-activation of iPads and iPhones – owe much to assistive technologies like the “no force” Fingerworks keyboard and Dragon NaturallySpeaking’s voice-recognition software.) As a field, Disability Studies intersects all disciplines, hardly reducible to an identity category or a single experience, which in part led me to “deformity” – a word that has intersected with many cultural groups across history – like Aristotle claimed that women were merely “deformed” males, and the list of associations deforms from there.

Mb: You run the Galerie de Difformité, a collaborative project to deform literature, both textually and physically. What is the goal of this project?

GH: There are many goals of the project: it’s an experiment to aesthetically redefine a word, “deformity,” which has deep sociocultural roots across many culturally marginalized groups. At the heart of that word is “form,” the basis of what we think about in art. The project is an intervention that questions our reading strategies and relationship with (un)making meanings. In the Galerie de Difformité, deformity hovers between object and subject, character and characterization, matter and metaphor, as the book as body deforms across material and digital realms, also intersecting institutions that carry cultural meaning: from pages-books-libraries, to exhibits-galleries-museums, to other orchestrated methods of (de)classification and (dis)play. It’s a novel. It’s a poem. It’s an art catalogue. It’s a method of criticism. It’s an exercise in slow reading and (in)accessibility. It’s also a project in pedagogy, engaging classes across disciplines at over a dozen universities, as professors and students navigate thinking and making conscientiously in the digital age. It’s part performance and installation art, popping up in various locales. It’s about our own relationship with our bodies, all of which are strong and vulnerable and knowledgeable in different ways. It’s about collaboratively searching through questions, literally and figuratively handling inherited notions of narrative and poetics, self and other, reading and writing, and much more, to implicate our engagements and collaborate in this quest of questions. Galerie de Difformité exists as a kind of living, growing organism – a “baggy monster,” as Henry James once defined the genre of the novel. The book is structured as a choose-your-own-adventure, so it’s as much about what you or I think, as what anyone else does. To quote one of the epistles in the echo chamber that is the novel: “Is the ‘deformity’ of the Galerie what’s included or what’s missing?” It goes without saying, a reader will get out of it as much as they put in. Since the project is embedded in varied media, parts will go defunct over time, and those absences and error messages also will become part of its narrative. There’s much more to say … essentially, the project has many goals, and I don’t know how the story ends!

Mb: What is the role of the body in art?

GH: Everything! Whether or not it appears, a body is always present in art. Bodies make art. Bodies see, hear, feel, think, and otherwise sense art. Bodies curate art. Bodies critique art. Bodies lambast art. Think of the old adage, “If a tree falls in a forest, and no one hears it, does that mean it really exists?” Artworks may survive on the planet beyond us, but if there are no bodies here to engage them, what’s the point?

Read more from / about Gretchen Henderson here. Buy a copy of The House Enters the Street here.

Edward J. Rathke is the author of several books, one of them published [Ash Cinema, KUBOA Press 2012], two more coming out soon, as well as various short stories online and in print. He writes criticism and cultural essays for Manarchy Magazine and regularly contributes to The Lit Pub where he also edits. More of his life and words may be found at edwardjrathke.com.