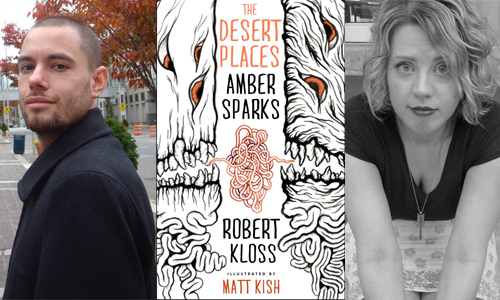

Robert Kloss is the author of The Alligators of Abraham. His short fiction has been published in Crazyhorse, Gargoyle, Unsaid, and elsewhere. He can be found online at robert-kloss.com.

Amber Sparks is the author of May We Shed These Human Bodies, released by Curbside Splendor in 2012. Her work has been widely published in print and online and you can find some of it at ambernoellesparks.com or follow her on Twitter @ambernoelle.

Monkeybicycle: Writing is typically a very singular and individual exercise, so how did this collaboration come about? How did you get Matt Kish involved?

Robert Kloss: Amber and I had talked about collaborating at some point, and Matt and I had talked about working on something, so it all fell together.

Amber Sparks: I didn’t know Matt, though I had admired his work very much, so that was a neat extra bonus for me — through Rob, getting to meet and work with Matt. I’d always meant to do something with Rob — in fact we’d collaborated small scale before — because in many ways we do share a sensibility. There are many contemporary writers I admire but could never do a project like this with, I think, because there’s not enough there to stitch together. Actually, contemporary may be the key word — in a way, both Rob and I have I think a sort of old-fashioned sensibility – so neither of us was very bothered by the others’ prose stylings.

This room: the dying glow of candles, the shadows of screws and knives and bolts and hammers hanging from the ceiling, from the walls. Had you a mother she would have smelled like this, of milk and dank and blood and mold. And the withered, white-haired men in single file who marched through the entrance, black robes and white robes and red robes. They called themselves ministers and judges. They wore beaded necklaces strung with the symbols of their god. They crowded over you, breathing and sneering. Brown-toothed, sour-breathed, muttering in aged prayer-speak. They read from dusty ancient books, in languages extinct or dying. They asked you the name of the god you worshipped and you replied, “Myself.”

Monkeybicycle: It does seem like the two of you have a sort of old fashioned sensibility, which is something I think I love about your writing. I know you’re both very into film as well, and this has cinematic dimensions to it, I think, especially with so much emphasis on imagery. Who and what are some of the biggest influences on your writing? And what specifically influenced the writing of The Desert Places?

AS: I’m definitely very influenced by visual images in general — by film, but also painting, photography, sculpture. When I write, it’s very much a collection of visual images — it starts with the description of the thing in my head, always. Always I’m painting in my pieces. Writer-wise, it really depends on when — right now, I’m very influenced by Nabokov and Woolf, and Joyce and Proust. (Lucky me!) But for The Desert Places, I was reading a lot of Rimbaud and Baudelaire, and I think that probably comes through.

RK: For my part, I think what influenced me was the other work I was doing at the time. I had this urge to write about something fantastic and bloody, partly because I had been writing about something fairly realistic and common.

Mb: The Desert Places is a meditation on evil and humanity. When you began writing, did you two have a goal in mind, or is this what naturally developed out of sharing words and pages?

RK: We had a goal in mind. I think we established an outline very early on, before any actual writing. I think that was necessary for a project like this — normally I’m happy with chaos, but a collaboration seems to call for structure, for guidelines, for territory.

Mb: So why write about evil?

AS: Well, good is boring. The bad guy is always the better character, after all. Evil is change, is the catalyst. So it’s naturally much more interesting to write about.

RK: Again, for me the idea was to write about a monster. An actual monster in the Grendel type. There was something about the idea that I found really compelling. That the book ended up being about evil was just the way we figured out how to frame it–but I really just wanted to write about this deathless fiend.

A: What do you dream when your belly is full?

O: I dream how I have filled the House of the Dead with the shades of men and women and children. I dream the bleating of the child and the cries of the father. I dream the mother scattered. I dream the house set ablaze. I dream ruination. I dream smoke. I dream flame. In other words, I dream smiling. I dream contented and pleased. I dream fat and healthy with the kill of the worlds.

Mb: At first when I was reading it felt like I was trying to pinpoint who was writing what. I’d read a paragraph and think, This is definitely Robert, or, This has to be Amber. So how did the collaboration work? What were the mechanics of the actual writing?

RK: We wrote individual pieces and then edited each other’s work. The idea was to cloud the authorship. It was interesting to find out how little I was willing to let go of, and how little I was willing to allow Amber to keep. I had to reflect on how much my tendencies were the right way or just the way that I had become comfortable with.

AS: Ha, that’s certainly true. I think I was much more comfortable with the idea of letting go of authorship a little. I’ve thought about that a lot, actually, because writing is usually such a solitary, single-minded thing, so what’s wrong with me? And I think maybe? it’s because of my day job. I work in a fast-paced communications team in pretty much constant collaboration. There are no bylines, and a press release or blog post or magazine or whatever might go through six, ten different hands before it goes to print. So maybe I”m used to working that way? Or possibly I just trust Rob and the vision.

Mb: It sounds like you guys worked pretty well together. Have you considered working together again?

AS: I think we did, yeah! We’re friends, too, so the whole process was pretty easy and fun and tension free. I’d work with Rob again, but I suspect he might have a different answer to that question, ha.

RK: It was a fun process, and I’ve kicked around the idea of maybe collaborating again. But I think for now I’m done with collaborations of any kind. I don’t know that I’m able to submerge my obsessions and inclinations for the greater work anymore. And I’ve mentioned this to Amber before, as her answer indicates.

Mb: And then this is sort of related, but where did Matt Kish’s illustrations come in? Did he create the images first, and then your writings were a response or dialogue with them? Or did he respond to the writing?

RK: Matt came in at the very end. Actually, I think it was around the time we heard from Curbside that I decided to ask Matt, which is amazing for me to realize because his illustrations seem so fundamental to the book. I can’t imagine the book without his work, but we submitted the book exclusively as a written work.

AS: Yeah, we are hugely indebted to Matt and to Curbside for having Matt illustrate the work. Because now that I read it, I can’t imagine we didn’t write with those images in front of us. It’s almost eerie.

Mb: It’s interesting that Matt’s illustrations came last because they feel so right within the book, almost as if they drove the book itself. How did the illustrations change the book? What dimensions do they add to the story?

AS: It’s hard to explain, but because they aren’t literal interpretations, I feel like they deepened the exploration of evil, the sense of story that was already there to begin with. They made it something wilder, something much older than human language.

RK: I’m not sure what they added — it just felt like the book took on a new size once we had them lined up. Obviously Matt is a superb talent and having his take on the material did reshape my conception of it. I don’t know how to articulate how it was reshaped — I suppose he just taught me to see the book in a different way than I had. I almost wished for a chance to go through it one more time to compete with his images.

The girl in the trash receptacle is not really a girl. Not anymore. She’s a trail of destruction, the crumpled instructions on how to steal the life from a body.

Mb: What The Desert Places lacks in narrative and characters, it makes up for in language, to the point that it almost feels like the language is assaulting you. How important was the style and language here? Why focus more on the concept than on any singular narrative? I’m thinking of how Nabakov, for example, demonstrated evil through Lolita.

RK: I think concept is related to the mechanics of the collaboration. We chose a book constructed of loosely related shorter pieces partly because that would allow for more initial control by the authors. I wrote a piece and Amber wrote a piece and then we’d throw them into the growing pile. Once we had enough material we revised each other’s work. We weren’t allowed to complain, although I did complain about somethings, which just shows that I don’t think I’d be comfortable with writing a single sustained narrative with another author — I need that aspect of control, even if I lose it during the revision process.

AS: I think both Rob and I are kind of obsessed with language, so it’s probably not too surprising that we produced a very language-driven book together. I would argue that there is a narrative, quite specific — it’s just told over a very long stretch of time, a very broad arc. It’s an ambitious narrative, and leaves out lots — but it’s still a narrative, I think. The story of evil, after all. It’s just more literal than, say, Lolita, because we’re writing about evil itself — not its incarnations, though they figure in as secondary characters, certainly.

Mb: What were the actual mechanics of the collaboration? Were you ever in the same room writing together? Was it all over email? Were carrier pigeons involved? Did one of you write a paragraph, send it to the other, and on and on?

RK: I actually think Amber’s early drafts focused more on character and story than the final versions — that’s because I edited the story and character out. Partly I (usually) find character and story less interesting than language and theme. Partly because I feel like the short-short form is most effective if it focuses on language and theme, rather than the development of character and story. But also because covering the amount of time and space and the big themes that we were developing in 10,000 or fewer words necessarily requires compression, and development of character and story work against compression. Finally, there’s just something about writing about the thing itself, the monster, and the force of the monster’s horrific deeds, that I really liked doing.

AS: What Rob said, except of course I’m going to disagree with him over the idea that character and story work against compression. I write a lot of flash fiction in a style I’m going to call epic flash, and some of the pieces I write are entirely character, or entirely story — and I think that can really work if you do it right. Some of my favorite flash is like that — basically a character sketch. And I think, despite Rob’s best efforts to deny it, that he’s really concerned with character too, just in a different way. (This is the part where I take my own life into my hands, ha!) I think character can be what comes out of an obsessive concern with language, the way that the character emerges through the languages choices that are made or rejected. There are so many character details in the book — I think you get a very good sense of who evil and what evil as been through, so much so that (I hope) that by the end you even feel a little bit sorry for this murdering force. Just like those movie monsters.

Mb: Who are the best, or your favorite, monsters in film and literature?

RK: I was always fond of King Kong. I watched the original King Kong maybe 100 times when I was growing up. And of course the point of King Kong wasn’t that Kong was monstrous but that humanity was. I think to some extent that relates to our book.

AS: I love King Kong, too — and like Rob, the original. I love stop-motion in general, like I suppose most 80s kids, so the Ray Harryhausen films are favorites — especially Revenge of the Titans. Even now (I know, this is horrible) that’s my Caliban (Calibos, but still), rather than Shakespeare’s Caliban. I adore the Universal Horror monsters from the 30s and 40s, especially Frankenstein’s Monster and The Wolf Man. And of course, I have a ridiculous soft spot for all the Gojira films, especially the original. It’s funny — going back to what Rob said about humanity being the villain — I think that’s always the case in monster movies, or at least all the good ones. The monsters may wreak havoc, but they can’t help their nature — and it’s usually the fault of the far-worse humans. Which I guess is a pretty good summary of our book.

Mb: What can you tell us about what you’re currently working on?

RK: I’m finishing a close to final draft of a novel. I have no idea if it’ll ever see the light of day, but I’ve enjoyed working on it more so than anything I’ve ever written. I’ve find it a very difficult and gratifying book to write, and I’ve pushed myself further than I have before, so whatever happens with it I have no regrets.

AS: Funny enough, I’m also finishing up a novel. Unlike Rob, I have not enjoyed the process of writing it — but I rarely enjoy the process of writing anything, so that’s unsurprising. I would rather clean up cat vomit than write. It’s editing I love — that’s where the work really becomes mine, my voice, my style, my shape and vision. It’s where the work sings. And so now that I’m editing, I’ve suddenly fallen in love a little with this thing that’s been pissing me off for the last year. So that’s kind of neat. It’s a global novel — it takes place in Paris and London and New York and Hollywood and Iceland and Ireland and Kenya . . . and I just realized that I apparently wrote a book about all the places I would like to travel to. So there’s that.

Read more from / about Robert Kloss and Amber Sparks here and here. Buy a copy of The Desert Places here.

Edward J. Rathke is the author of several books, one of them published [Ash Cinema, KUBOA Press 2012], two more coming out soon, as well as various short stories online and in print. He writes criticism and cultural essays for Manarchy Magazine and regularly contributes to The Lit Pub where he also edits. More of his life and words may be found at edwardjrathke.com.