“Is she making wishes?” my daughter asks, ten minutes into her incessant, idle chatter. Her tone switches enough for me to notice, to pay attention, and finally: silence.

“Who?”

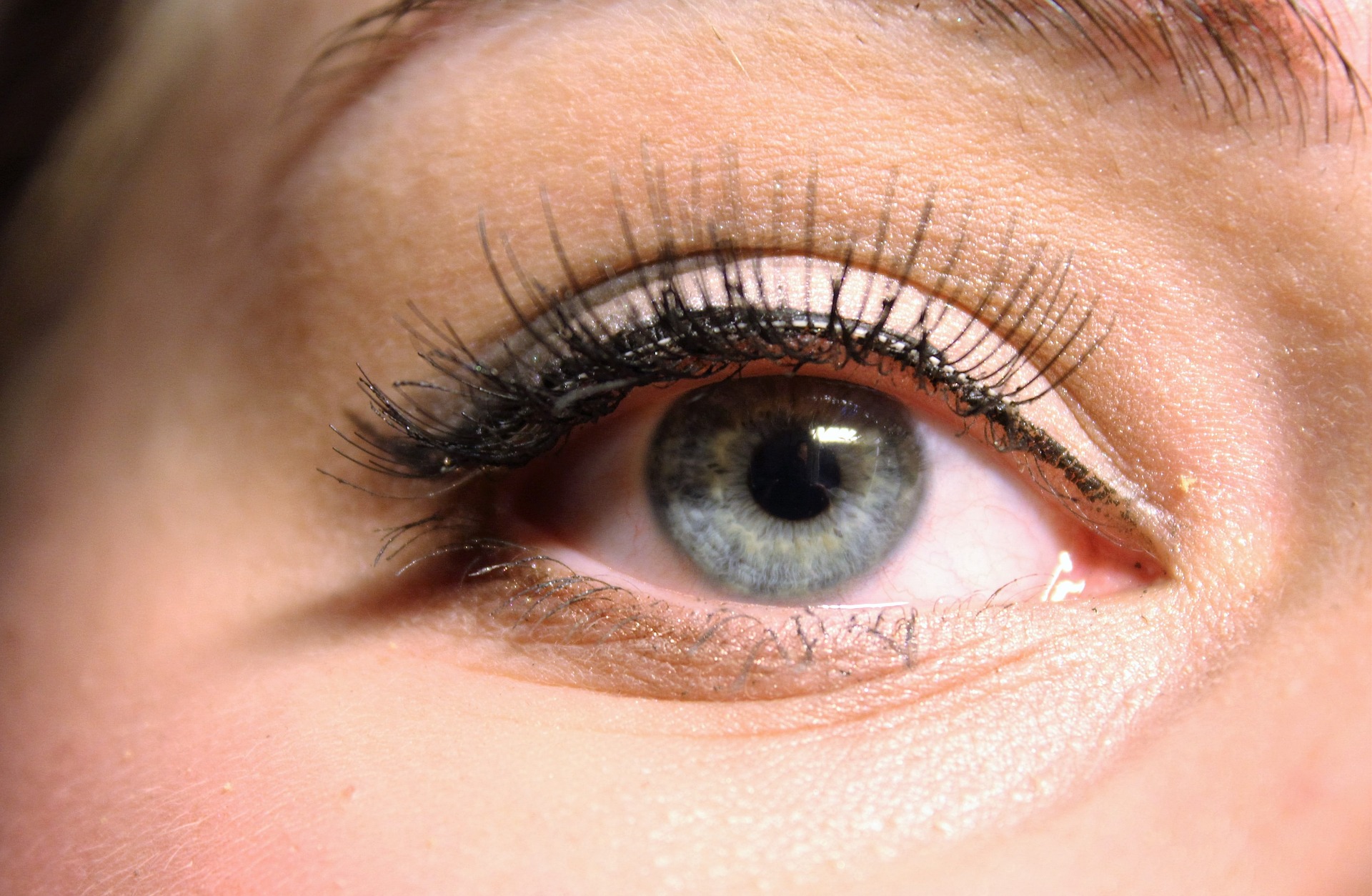

She doesn’t reply. Her eyes are closed. Her fingers, nails filthy and needing trimmed, press at the edges of her eyelashes.

“Who, baby girl? Who is making wishes?”

“The lady.”

I look around. Our new backyard is vast and wild, like everything up here. But it’s barely been a year since Brandon and I finally finished renovating our yard, my dream garden in my dream house. I’m talking magazine-worthy outdoor living. Woven hammocks. Solar-heated, cedar-planked hot tub. Cement fire pit. A swingset for Isabel.

All that to this: Rusted, cobwebbed chain-link stands askew at the property line, against the gnarled trunk of an olive tree, the only tree we have. If I squint, I can see the potential. A vegetable bed just outside the backdoor, where we’ll actually use it. A small bistro table, two chairs. I’ll drink my morning coffee out here and let Isabel steal sips while she picks at her toast. Or maybe we can afford something fancier than toast, living up here, away from city mortgages and city expenses. Away from Brandon.

“She’s right there, Mama.”

Through the side fence and up the slope a little sits our next-door neighbor’s house, nearly out of sight. We’ve never seen, let alone met anyone, but it’s only been a couple of days. The house is in the sort of disrepair that some realtors would consider a blight on a “location,” but my realtor only shrugged. “It makes even your house look good,” he said.

On the back porch stands a woman. Not too old, but frail. What I guarantee Isabel is just about to describe as an “old woman.”

“The old woman,” she says. “Pulling out her eyelashes.”

The woman lifts her free hand to wave. “Hello there.”

I walk to the fence, summoning Isabel to follow. “Hi there,” I call. “I’m Lara, and this is Isabel. We just moved in.”

“I’m Penelope Blackburn. Call me Penny,” she says like a business transaction.

I try to get a closer look, mostly to see if she is literally removing eyelashes, but she’s too far away. I don’t know if I’d notice anyone’s eyelashes unless they were remarkably fake.

“Don’t be shy,” Penny says. “Come on over.”

She nods to an inconspicuous gate between our backyards. It’s the same chain-link as everything else around here, a tie made of a torn strip of blue tarp. This town is all blue tarp and chain-link, mixed up in devastating natural beauty. I unwrap it and try to shove the latch.

I never know if Isabel is going to be shy around someone new, or chatty. I’m not exactly a shining example of how to talk to strangers. Isabel’s world is small: me, her father, distant grandparents, and one teacher in a class of five other preschoolers. That’ll all be changing soon. A bigger school, more time away from me, and the uncertainty of her father’s world.

“Hi, Penny,” she says, squirreling her way past me through the gate and skipping ahead. “Pleased to meet you.”

The dust in Penny’s house is enough to make me cough. But she brews us some tea, and Isabel is happy, so I don’t want to hurry.

“Well,” Penny says, as I’m just about to stand up to leave. We’ve been here nearly an hour, but I get the sense she’s held back on what she really wanted to ask. “What brought you up here, Lara?”

I’d wished to start over up here, free of Brandon’s baggage, free of the city’s baggage, free of my old life. I could be anyone. But I could tell, from only an hour with her, that bullshit would not work on Penelope Blackburn.

“Divorce,” I say.

She draws a long sip from her teacup. Her fingers are crepe-like, nails yellowed and jagged. Her lips are cracked-dry, and I take back everything I first thought about her age. She seems older than anyone I have ever known.

“Seems as good a reason as any,” she says.

* * *

It’s a week later when I can’t find Isabel. I don’t remember the last time I saw her. One minute? Ten?

Fear takes hold in strange ways as a mother, and it’s never anything I can predict. I’ll panic imagining the most absurd stuff: rubbery shoes getting caught on a playground slide, little legs snapping in half or the car being T-boned on Isabel’s side. And sometimes, in the face of actual danger, I’m calm: singing nursery rhymes while applying pressure to gaping wounds, walking slowly backwards from a rattlesnake, her hand in mine, whispering reassurances. And now.

“Isabel,” I say, steady. I walk through the house. It’s small, the smallest place I’ve ever lived in after college dorms, but it seems to take forever to look everywhere. “Isabel.”

I burst through the front door and oh, there’s the panic. “Isabel!” I call, my voice breaking. I expect to see aghast neighbors leaning in doorways, looky-loo cars stopped, her body crushed against the front grill of some 18-wheeler. But nothing. A car zooms by and I flinch.

Once more through the house I still can’t find her. Out back, I untie the strip of tarp and march into Penny’s yard. I don’t simply imagine the worst, I imagine beyond the worst. The logistics of it. Calling Brandon.

Penny’s back door is wide open, but I haven’t seen her in days, so I let myself in. “Isabel?”

Her place seems even less lived-in than before. Drenched in dust, faded, impossibly cluttered and sparse at the same time. And then I hear a quiet voice from above, but distant.

“Mama? Mommy?”

I wonder if — god help me — Isabel is somehow up on the roof outside, but then I see the ladder, propped against a closed attic door. I want the superhero mother rescue strength to kick in, but it doesn’t. I move slowly, unsteady footing barely holding as I climb the ladder and I imagine dying this way, my body contorted on a splintery floor, impaled by a ladder rung, with Isabel waiting for rescue.

“Hang on, baby girl,” I say in the cheeriest voice I can muster. “I’m coming.”

At the top of the ladder, the attic door lifts easily. Hoisting myself up, I’m surprised by how tidy it is. Isabel sits criss cross on the floor. “Look, mama,” she says. “Treasure.”

I don’t know how Isabel got up here. I don’t know why I can’t ask her. Maybe it’s the potential for an answer I’m unprepared to hear.

She’s surrounded by boxes and boxes of jewelry, all of it plastic costume stuff. Dull gray patches show beneath flaked-off bright jewel-toned paint, metal plating chipped and blackened. Each specimen nests carefully in its own custom box, a museum of a past life, a pride in small luxuries. I imagine a girl: Penny, raised in a run-down mountain town with nothing to dress up for, pulling each necklace from its tiny home, carefully draping it around her small neck, collar bones jutting as she reaches behind her to clasp it. A twirl in the mirror, a hairbrush microphone, Ella Fitzgerald, Judy Garland, Édith Piaf, a wisp of a wish of another life. Then tuck it all neatly away.

Looking up, I notice an oval, gilded-framed mirror, hung with satin ribbon from a nail in the attic wall. And when I catch my reflection, I find my hand hovering near my eyelid, finger and thumb pinching, tugging. My inhale is sharp and jarring, and when I look at my fingertips, there’s not one eyelash—there are three. Make a wish, a wish, a wish. I hadn’t even noticed, I hadn’t even noticed what I was doing.

If I had all the wishes, a body’s worth, what would I even wish for?

“Let’s go home, Isabel. We shouldn’t be going through Penny’s special things.”

* * *

Morning light pokes gray through the blinds in my bedroom. It’s still cold, and I love this mountain weather. I roll over to reach for my phone, not that anyone will have texted me or tagged me or even thought of me. Next to my phone sits a small glass, tiny, like a thimble, like a doll’s glass. My heart quickens, and somehow I am heavy and weightless at the same time. In it, barely visible, is the tiniest cluster of hairs, and I know right away it’s a lot of eyelashes, my eyelashes. All of them. I close my eyes and slowly bring my fingers to my eyelids, the way Isabel did that first day we saw Penny.

* * *

“Wake up,” I say, aiming for sing-songy but landing on freaked out. “Come on, we’re going down to the city.”

I pick Isabel up and carry her to the toilet, sitting her there. “Pee,” I say. “Come on.”

On my phone, I thumb in CVS to try to find the nearest one. Thirty minutes. I give Isabel a granola bar for breakfast.

I blink a hundred times. Nothing feels different, nothing hurts. I’m just without eyelashes.

I’m feeling, more than anything, a little without my mind.

* * *

In the bathroom at CVS I dump out the bag on the counter, tearing into the packaging. First the false lashes. Then the glue. I drop the cap on the ground and grit my teeth, grunting in frustration.

“Mama,” Isabel says.

“Not now,” I growl.

“Mama,” she says again. “You’re scaring me.”

The panic sets in: my child is in danger. Do something. It’s a simple solution, unless I’m the danger. If I’m the problem.

* * *

At home, my tires crunch in the gravel driveway and I stop a bit too abruptly; we skid a few feet further. But I’m on a mission: I am going to find Penelope Blackburn, and I am going to give her a talking to.

I carry Isabel, her too-big-for-this body perched on my hip, through our own house, down the back steps, through our wild, disheveled backyard (just to my right: that’s where I’ll plant the vegetable garden this spring, just to my left: that’s where we’ll put our bistro table), unwind the tarp strip, open the gate, and up to Penny’s back door. I start to knock.

I blink repeatedly, fake eyelashes heavy, almost clouding my vision with the weight.

“I think you should leave,” Penny says through the door. There’s a long pause. The back door unlatches and the door creaks slowly open.

I notice the tension in my shoulders and the way I’m gripping Isabel before I realize I’m afraid.

“I’m not feeling well,” Penny says through the screen, which she does not unlatch. I suddenly feel ashamed, and I suddenly feel pity, and I suddenly feel worried about Penelope Blackburn. “Go on now.”

We take a step backward.

“You going somewhere fancy?” she asks, gesturing to my face.

“No,” I say. “No, I’m not.”

I walk backward, Isabel’s small, clammy hand in mine, until I get to the gate, and then I close the gate, rewrap the tarp strip, wave at Penny, walk slowly into our house, and close and lock the backdoor.

Isabel stops at the toy box in the living room, but I keep walking, into my room, past the nightstand, and gaze into the wood-framed mirror on my dresser. I close my eyes and open them, the new weight of my lids a perfect heft, and I think I got a little glue in my eyes earlier, my vision blurred, the world hazed. I don’t know if I’m scared anymore. These eyelashes are lovely.

Julia Dixon Evans is the author of the novel How to Set Yourself on Fire(Dzanc Books, 2018). Her writing can be found in McSweeney’s, Hobart, The A.V. Club, Literary Hub, Pithead Chapel, Paper Darts, and elsewhere. Her short story “Vinegar on the Lips of Girls” won the 2019 National Magazine Award for Fiction. Twitter: @juliadixonevans