Simon Pinkerton

I would find an inky discharge in the sink after she would so carefully and at such great length set about making herself up. I assumed it was mascara, or something else from her array of cosmetics.

“Concealer” is what the French would describe as le mot juste.

She would emerge, immaculate and painted, from within a cloud of steam that puffed out hard when she finally opened the door, and then she would go to whichever club or course it was she wasn’t really attending at all.

She would go to see him, or she would go to see her. Maybe some nights she saw them both.

She would return to me, and she would be attentive, and appreciative, and full of love. She had a lot of love to give, a capacity far greater than most. Romantic love. Not compassion.

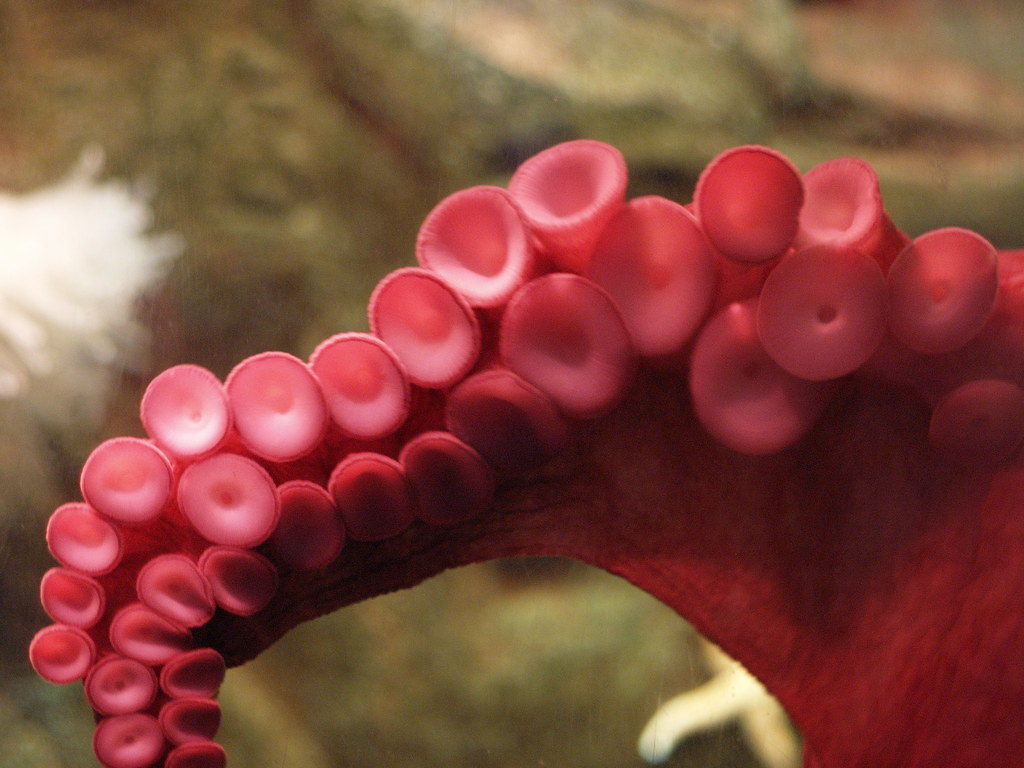

I watched a documentary. An old man with a soothing, unhurried voice described them as intelligent, different, a mystery; diverse in their activities, and venomous.

She was talented, juggled so many things at once, so many interests, and I with my standard biology was nowhere near enough for her. I wanted her so much I denied what I saw, and I knew I was doing it. I didn’t want her soft body to slip away from me.

I wonder what I could have done differently. How I could have been different.

Octopuses have excellent eyesight and she saw how she wanted it to go from the start. It was nonsense to even entertain the idea of keeping her. I didn’t have a habitat big enough. She wouldn’t have been able to breathe.

I followed her to the quayside and I saw his eyes light up when she glided over, and I doubled over, deflated and poisoned.

I collapsed onto my knees. She saw me, and her eyes widened: astonished; trapped, just for a moment; and then she bolted, and in an instant she was camouflaged in the crowds walking the promenade between bars and restaurants. I wailed. Row-boats hanging ornamentally from the walls of buildings either side of me were all I could see peripherally, my vision clouded, murky.

I held my breath.

It was the last time I saw her.

In the days after, I would see him, looking out over the water, when I went there to do the same.

I spoke to him. He didn’t know about me, only the other girl. I hadn’t known about either of them. I wondered who the other girl knew about.

It makes sense, I told him. An octopus has three hearts. He gave me a look I would characterise as knowing.

A month later he wasn’t there, and I overheard a bartender talking about some guy who had jumped into the ocean right next to the place, whom they never found, even with boats and frogmen.

I understood. He’d gone after her.

I remember how his neck was always covered by an upturned collar, always. Now I knew why, what he was hiding. It got me thinking, and worse, it gave me hope there was something I could do, some way I could change, to jump into the water and find her myself.

Simon Pinkerton writes novels, short fiction, and humor, and is from London, UK. He writes for a ton of magazines and is currently seeking representation for his first two novels, or maybe just one of them. He has a lot of people he’s told he’s gonna be a big shot over the years —don’t make him look stupid now. Find him on Twitter at @simonpinkerton and at www.simonpinkerton.dx.am.