Brittany Harmon

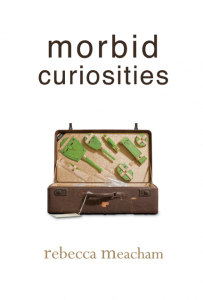

Reading Rebecca Meacham’s work is not unlike opening a cabinet of curiosities and falling into each object’s rare and unique past, a time capsule for the strange. However, as the title suggests, these curiosities are strictly morbid, a natural disaster’s first-person account of destruction, a freakish exhibit on a pier, recalling, at times, Philadelphia’s own Mütter Museum of medical oddities, shrunken heads, and antique scalpels. Meacham transports the reader from 1878 Paris to present-day Disneyland with the finesse of a historian and the pathos of a refined storyteller. These short pieces will mesmerize and frighten, as well as affirm the power of language and brevity. Morbid Curiosities reminds me of my favorite photographer, Diane Arbus; although her subjects were marginal people—twins, giants, nudists—she did not merely wish to present them, but to show that there are resonances in anomalies, traces of beauty in horror.

Reading Rebecca Meacham’s work is not unlike opening a cabinet of curiosities and falling into each object’s rare and unique past, a time capsule for the strange. However, as the title suggests, these curiosities are strictly morbid, a natural disaster’s first-person account of destruction, a freakish exhibit on a pier, recalling, at times, Philadelphia’s own Mütter Museum of medical oddities, shrunken heads, and antique scalpels. Meacham transports the reader from 1878 Paris to present-day Disneyland with the finesse of a historian and the pathos of a refined storyteller. These short pieces will mesmerize and frighten, as well as affirm the power of language and brevity. Morbid Curiosities reminds me of my favorite photographer, Diane Arbus; although her subjects were marginal people—twins, giants, nudists—she did not merely wish to present them, but to show that there are resonances in anomalies, traces of beauty in horror.

Brittany Harmon: This is a magnificent collection that weaves together myriad genres, forms, and influences. Does the idea of postmodernity shape your storytelling, or is hybrid fiction a gut reaction to our hodgepodge, fragmented culture?

Rebecca Meacham: This question reminds me of when I was studying for my doctoral exams and got stumped by the term “postmodernism.” I’d read all these conflicting theories; I was so confused. So I called my professor, Tom LeClair, and asked, “Why is there no stable, unified definition of ‘postmodernism’?!” To which he replied, “Exactly.”

Rebecca Meacham: This question reminds me of when I was studying for my doctoral exams and got stumped by the term “postmodernism.” I’d read all these conflicting theories; I was so confused. So I called my professor, Tom LeClair, and asked, “Why is there no stable, unified definition of ‘postmodernism’?!” To which he replied, “Exactly.”

So it’s hard for me to place this collection in a category. Maybe that’s because my fiction starts with a curiosity about something small, almost hidden, that I’m trying to uncover. Each of stories in Morbid Curiosities began with an enticing, irresistible detail: gossip about a woman goaded into making a death mask—or a stylist giving a murderer a haircut. There really was a Princess Alexandria of Bavaria who, in the mid-1800s, suffered the delusion she’d swallowed a grand glass piano. In each of these stories—including “Swath,” which is from the point-of-view of a tornado—I’m overlaying fiction on a headline, or found object, or “true story.” Some characters are famous, like Mitt Romney. Others are anonymous, like the voices in “Cases,” a story based on Jon Crispin’s photographs from the Willard Asylum for the Insane.

As I wrote, I pulled in materials that I, a privileged American in the 21st century, can easily access: current headlines, archived menus, an 1874 primer, blueprints of amusement parks. So I’m a fan of our hodgepodge, fragmented culture!

I guess another “postmodern” aspect of the collection is its interplay between private loss and public spectacle. In some cases, the spectator is a collective voice, like the tourists in “Beached,” who watch a seal die, but they don’t understand the complexities of the scene. They just want their daiquiris. I also position readers as confidants —as with the Indian Boarding School girls in “Exercises for Printing and Writing,” who use their English lessons to expose an abusive schoolmaster. The primer is their tool of vengeance, a secret we’re all meant to hear.

BH: Many of your stories are rooted in a specific location. How important is place in your writing, and what attracts you to these settings in particular?

RM: Morbid Curiosities started when I was trying to write a novel about Peshtigo, Wisconsin, and a big, tragic fire there in 1871. That novel peeks through one of the flash fictions in the collection—“Mrs. Williamson Winds the Watch”— and for months, I was trying to understand what Door County soil was like to an immigrant farmer (answer: rocky), or if a general store might sell postcards at that time (answer: no).

So when I’d rebel against the novel and write a flash piece, I was drawn to places that generated a larger story: Coney Island’s exhibit of premature babies in the early 1900s, or Pensaukee, Wisconsin’s 2003 missing-woman case.

Because flash fiction is, by definition, a form of few words, titles can do the work of establishing time and place. So, many of my titles tell readers what my characters cannot.

BH: Some writing professors have a strong aversion to flash fiction. What would you say to those who are of the opinion that flash fiction is just an easy way out of writing a more substantial story? What does flash fiction have to offer that longer pieces do not?

RM: Flash fiction is controversial? Finally, I’m cutting-edge! You know, I’m teaching flash fiction to my advanced fiction workshop, and these students will also write traditional-length short stories, and some will take my novel-writing workshop. To me, flash fiction is just another genre, with elements that define its shaping and the reader’s experience of it. Like any other form (novel, short story, sestina, haiku), if the work feels unfinished, then it’s not good writing.

For me, as a writer, the constraint of flash fiction presents an interesting challenge: how much can I stuff into this space, while also creating emotional impact for the reader and a sense that something has happened? As with a traditional short story, I want a reader to finish a flash piece feeling tense, unsettled, or moved; as with a poem, I want the piece to progress in its disclosure of information, or its emotional pitch, as it unfolds.

I love cake, so I’m going to try a cake analogy. Good flash fiction is like a slice of ten-layer cake: complex, towering, marvelously constructed, and capable of making an impact. We can taste the grains of sugar, savor the texture, and wonder at that one ingredient we can’t identify, but that makes all the difference. Our entire being is engaged, briefly— and with complete satisfaction.

(Where this fails as an analogy is that I can always eat more cake. So maybe flash fiction is like a tart. Or an orange. Or a really good guacamole.)

Learn more about Rebecca Meacham at her website. And find her on Facebook and Twitter.

Brittany Harmon is a writer and graduate student at Wesleyan University. Her work has appeared in The Philadelphia Review of Books, Dogzplot, and Sundog Lit. She lives in Connecticut. Find her on Twitter here.