Reviewed by Robert Long Foreman

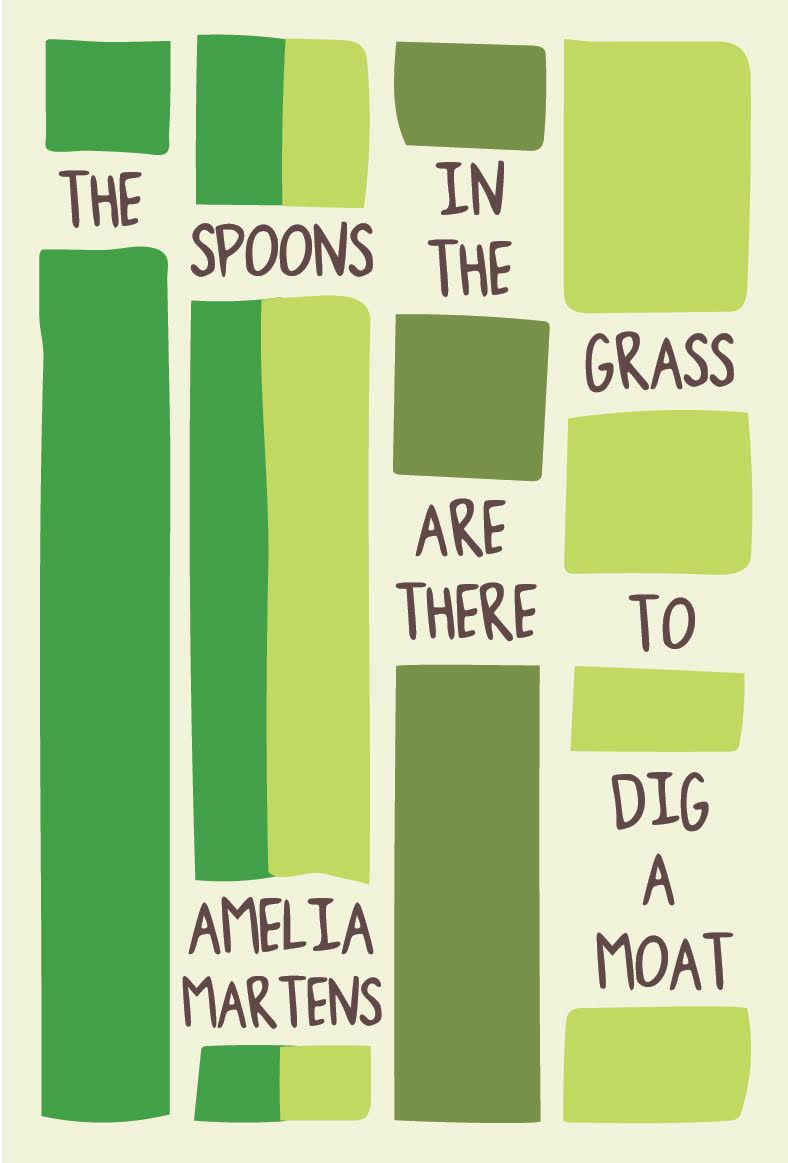

The Spoons in the Grass Are There to Dig a Moat, Amelia Martens

Sarabande Books

ISBN: 9781941411230

$14.95, 64 pages

The 54 prose poems in Amelia Martens’s collection, Spoons in the Grass are there to Dig a Moat, feature a cast of characters that includes small children, Cinderella, multiple Lincolns, and Jesus. The collection tangles these figures together in scenes pastoral and domestic, as it reaches through the surreal in order to grasp some of the most exasperating, painful aspects of our daily lives.

What distinguishes the collection at first glance is its use of Jesus, who appears and reappears throughout it in modern predicaments. In “Baggage,” he “waves his wand over abdominal muscles buried under a sea of fat.” He is working at an airport security station, where he thinks “about a gun made of socks, what two hands could do with a bra stripped of its underwire, how easily books might bludgeon,” until he is pulled away from his station because “his eyes and beard are making people uncomfortable.” There is a subversive humor at work in this and other poems, as we see Jesus do things at times very Christ-like and at other times not especially Christ-like. Or, perhaps, he is always the solemn Jesus we expect him to be, but the situation he is placed in confounds and warps him.

The Jesus of The Spoons in the Grass is a messiah who has been applied to certain situations like butter spread across toast; he is essentially the same savior as always, but he has been altered in the process of his application. In “Middle America,” “In one hand Jesus holds a seed: a brain, already mapped and waiting for a cloudburst. He can feel the most delicate trigger, the fingers of farmers as they steer wheels of two-ton machines and turn soil into something else. A landscape scraped of grass once blew away for an entire decade, and Jesus knows it could happen again.” In “Newtown,” in the aftermath of the schoolhouse massacre, “Like a cement statue, Jesus sits amidst a funnel cloud of flipped-over plastic chairs.” The Jesus of this prose poem brings with him the nuance he has gathered about him in his prior appearances, and yet he is at the same time the very Jesus the poem needs him to be, a mute rebuke to the horrific event that the poem commemorates.

In many of the other poems, children arrive at the reader’s feet with all the complexity of children intact, with the bizarre worlds they inhabit, and the existential challenges they pose to those who are responsible for them. In the book’s opening poem, “The Apology,” Martens writes,

Our daughter thinks you are a giant. She asks you to lift the house, so she can put her dolls in timeout. There is a crack in the back of my mind and I am filling it up with forget-me-nots and sailor’s knots and do nots. There is a place behind my retina where I am fragile.

It is the proximity of the child’s fantasy of the lifting of the house and the speaker’s aside, the “crack in the back of my mind,” that makes this so recognizable a depiction of being a parent to a child. The desire on the part of the child to see the impossible done so that something mundane can be done bleeds into a note of muted distress, the fracture of the speaker’s mind, the concession that she is “fragile.” This sense of wonder and sense of corrosion are layered together in the poem as they often are in the life of a parent, or life in general. “I should turn my head,” writes Martens, nearer to the end of the same poem. “I should stop watching you while you sleep because I am going to wake you up. I am going to wake up.” This would be sentimental were it not for the distinct impression of the distortion of this speaker, the fragility she volunteers, and the impression given that the presence of the child in the poem and the trouble to which the speaker is so resigned go hand-in-hand.

“Every morning our daughter builds a small memorial,” begins “Union.” “She gives us each a flowered plastic plate of plastic cake, so we can remember her when she dies. She cries because her hair isn’t fixed right.” In this is a perfect rendering of the psychology of a child—depth and gravity, right beside a total lack of perspective. The child “wants to know more about the chicken in my thigh, the blood in the toilet bowl. What color are my insides? Of my egg? Am I yellow?” The poem concludes,

She cries because federal employees can’t receive presents, then works for hours with a small chisel and pick. During lunch she announces apologies and future plots. She wants to take my heart out and sweep every room.

Soon after I read The Spoons in the Grass, I talked with a friend about the right way to write about children—not that there is one; I was just talking. I said that to do it right it has to be done with the understanding that in the relationship with one’s own children a great deal is taken away; that having a child, and raising a child, is a kind of loss, one that from the outside seems unlikely, and must seem to some an unfathomable paradox.

I was talking, really, about these prose poems by Amelia Martens. The Spoons in the Grass is overwhelming, and heartbreaking—a book that processes, through the unique mind of its author, more things than I can list here. In this book are losses upon losses, the love and impossibility of children, and a frequently alarming, but always strangely accurate, depiction of the country we live in.

Robert Long Foreman’s fiction and nonfiction have appeared most recently in Copper Nickel, Shirley, River Teeth, Redivider, and The Collagist, among others. A collection of his essays, AMONG OTHER THINGS, is forthcoming from Pleiades Press, and he has written WEIRD PIG, an unpublished novel. He is Fiction Editor at The Cossack Review. Find him on Twitter @robertlong4man.