Charles Rafferty

A man wished to become notorious, so he purchased “The Birth of Venus” at auction and burned it on live TV. People were outraged. Afterward, at the press conference, he took a long sip of his mimosa. “With great wealth comes great privilege,” he told the journalists. “Surely that much is clear in an age when artists cannot afford to rent the rooms where their unsold paintings must languish.”

Such answers only incited those who stood before him like a bunch of captured chess pieces, but the complete rejection of his ideas convinced him he was on the right track. The true genius, he knew, was always out of step with his times. He vowed to buy and burn more paintings. The ratings for his Thursday night TV special were unprecedented. It was as though people actually went out and bought televisions for the occasion, so alluring were his crimes.

Lawyers and art lovers alike were unable to stop him. There was no law that compelled one to preserve private property, and at auctions, it was easy to find stand-ins—people who would pretend to not be maniacs so that he could get hold of whatever paintings he desired.

“My hope is to fit every extant Manet inside the cylinder of one of those large ashtrays they used to have at the mall,” he said. “I’ll use the ash to fertilize my tomato garden.”

Very quickly, people realized that even bankruptcy was beyond their hope, for the man who would be notorious gave an interview in which he revealed that the money he took in from advertising during his live TV specials was more than enough to replenish his coffers.

Naturally, that’s when the assassination attempts began. And because notoriety depends on accessibility, he often appeared in public to burn a painting while wearing fresh bandages from his latest attacker.

“I could go on like this indefinitely,” he said. “I’m like an oil stain on the floor of your father’s garage.”

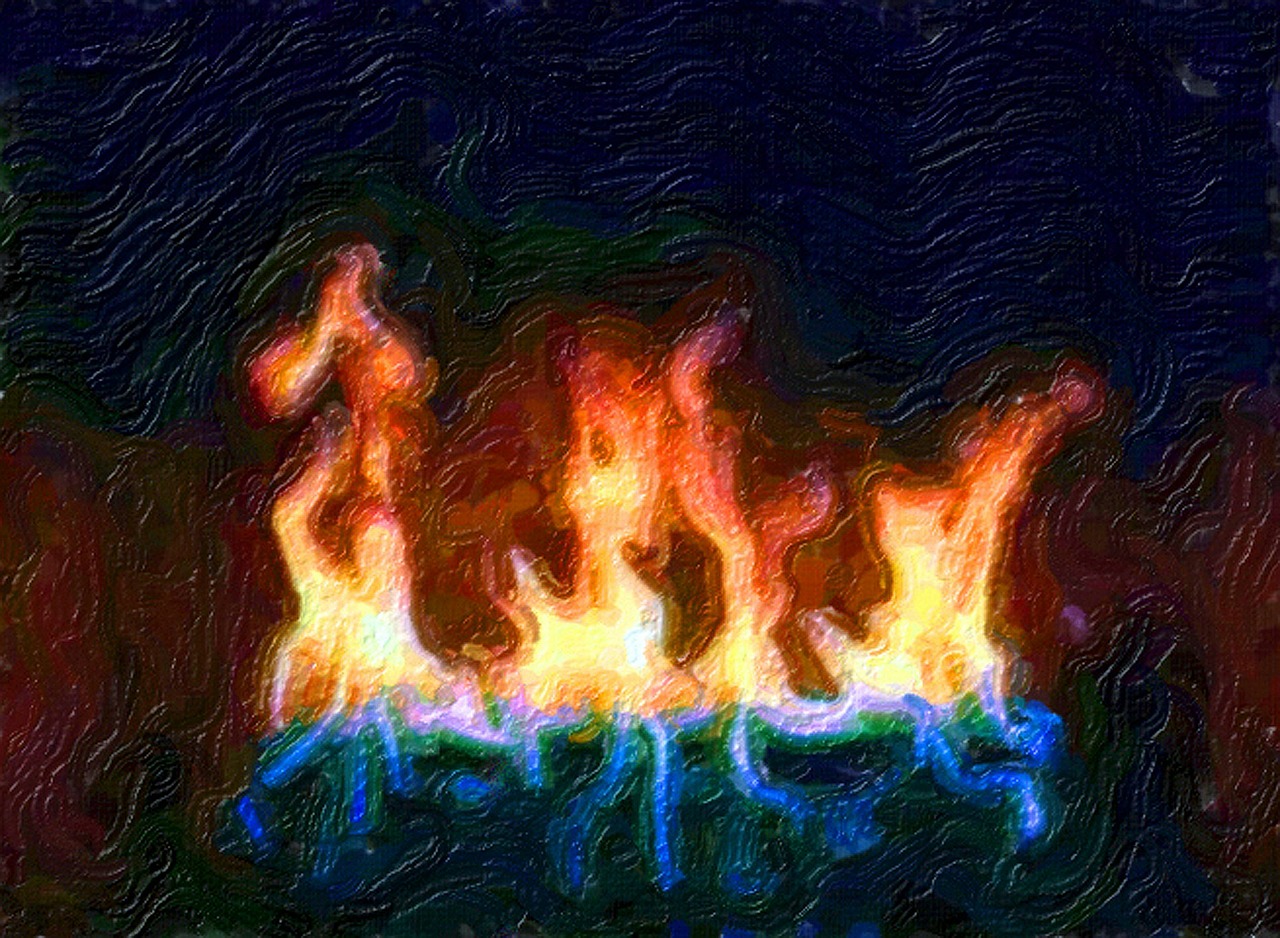

On camera, he burned the paintings invarious ways — sometimes with a surgical blade of acetylene, sometimes byflinging them face up into a roaring bonfire of Catchers in the Rye marinated in gasoline.

On a whim, he began to sell the charred remains of the paintings. To everyone’s astonishment, they sold well. His most expensive burned painting was one of Van Gogh’s “Sunflowers.” He bought it for fifty million but sold the burned version for fifty-five. It was basically just a frame and a halo of charred canvas with the signature still showing. He signed his own name on top of it, and it became the most visited painting in New York City.

When he finally made off with the “Mona Lisa,” the world slipped into a state of shock. Even people who hated art felt uneasy. Could they really stand by while a symbol of cultural excellence was incinerated at the Super Bowl halftime show? Could they really keep from clapping?

“We all have aspirations,” he said. “It’s rare that we ever achieve them. After this painting, there’s not much point in going on.” He took a long drink from his press conference mimosa. “I’m thinking of turning to statuary, sculpture. Or maybe famous documents — like the Magna Carta, the Declaration of Independence.”

When the booing died down, a journalist spoke up. Yes, she understood his craving for notoriety, but why paintings? Why destroy art? With so much money, he could have set his sights on anything.

“I’ve always loved painting,” he said. “But I hadn’t any skill. True value can only be fixed when something has been destroyed. I’ve been burning my own paintings for years, and no one has noticed.”

He went on to explain it’s like the way our feelings about our parents change after they’re gone. Or when our favorite show gets taken off the air midseason. The test of their value is whether we miss them.

“If the show was any good,” he said, “when 8:30 rolls around on NBC, you should feel like rioting.” He drained the last of his mimosa and stepped into the bulletproof limousine that was waiting to take him home.

Strangely, there were painters who came to his defense. They saw it as a clearing of the field, a way to have their own work taken more seriously. After all, if the museum walls are empty, they need to be filled with something. The feeling these artists had when they saw a painting burned on live TV was not unlike an average man being at a party and realizing the most handsome man there was gay. It meant you had a shot. It meant you might get lucky.

Charles Rafferty’s eleventh collection of poems is The Smoke of Horses (forthcoming from BOA Editions). His poems have appeared in The New Yorker, O, Oprah Magazine, and Prairie Schooner, and are forthcoming in Ploughshares. His stories have appeared in The Southern Review and Per Contra, and his story collection is called Saturday Night at Magellan’s. Currently, he directs the MFA program at Albertus Magnus College.