Patricia Q. Bidar

In our ordinary town, it was summer when the vanishing began. They started small—a couple of eggs from a molded cardboard carton Willie and I had argued about the correct way to deplete. Empty one side first, or alternate ends so the container is less likely to be lopsided, then dropped? In any case, even though Willie and I had had this disagreement, we still didn’t notice when a couple of eggs went missing. Neither of us is big on breakfast.

Next door, the Fleishhacker twins both had their swimsuits and goggles turn up missing. They first blamed their kid brother. Then Mrs. Fleishacker. Then they turned on each other.

Framed photos. Colored paper. Table lamps. Then jackets and sweaters. But it was still Daylight Savings. The air, heavy with heat. Then the pools all went. Above ground and molded plastic. In-ground and blow up.

All over the town, couples whispered about it in their beds. Kids repeated stories they heard from their parents at dinner tables, before the tables all went. No one cared about the losses of others. We’d long since emptied of compassion, having poured it into the crews and squads we’d nurtured on Instagram and Twitter.

Nobody even tried changing things. The couples who still made love continued to do so, and those who’d abandoned the practice didn’t start up again. The same went for prayer. No one learned to cook a special dish or learned a new language.

Buses vanished. Then cars. With the first appearance of orange leaves, the WiFi stopped. Gone in a blink with all our devices. Our selfies. Our contacts.

Shops. Schools. Offices. The titty bar on the highway at the west side of town.

Technically, we saw more of each other than we had in years. At the city council meeting held in the dirt where the City Hall once stood, Miss Penny, the children’s librarian, quoted Rilke and his mandate to “love the questions themselveslike locked rooms and like books that are written in a very foreign tongue,” she intoned, drawing herself up to her full height “Do not now seek the answers, which cannot be given you because you would not be able to live them.”

The mayor thanked Miss Penny without comment. Like everyone, he was only waiting for his own turn to talk. No one had had a two-sided exchange in forever.

There was no one to round up and punish. No one to make an example of, however much all of us burned to see someone pay. The need for it flared in our chests as we who remained strode to our homesites, avoiding eye contact.

Or had the no eye contact thing ended before the vanishing even began?

In our town, the missing items were like black spaces where teeth had been. We’d never seen anything like it. But then again, remember, nobody had actually noticed until the big disappearance was already underway.

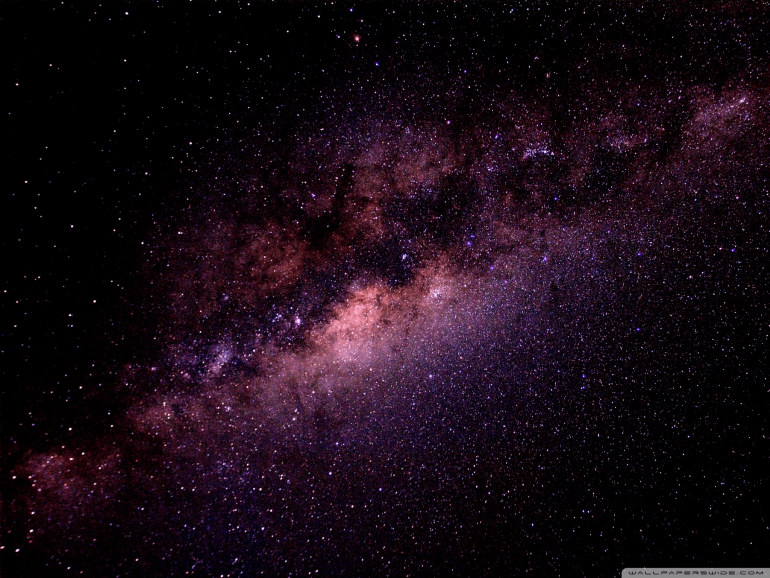

Gardens. Dirt. By now our town was like a crossword puzzle, connected horizontally and vertically and floating in an expanse of black. And finally almost everything was gone, with just our half-furnished homes and shops to show we’d ever been there. And us.

Some diehards still posted their opinions and maxims. But now “posting” meant literally that: writing something out on white paper—we still had that—and affixing it to the remaining streetlight poles. Bragging was still a thing, but barely. Someone had illustrated a Dr. Brené Brown quote about hope, with irises and hyacinths. Like the brags, it was ignored.

The comments sections, affixed pages below the initial posting, were as brutal as ever.

Could we have stopped it with vigilance and a can-do spirit uniting the town? It’s impossible to know. Despite the years of doom-scrolling, doom and doom and gloomy doomy pronouncements, no one ever really thought we’d lose the things we took for granted.

We thought until the very end that everything would come back.

Hope, Brené Brown tells us, depends upon awakening and believing the day will hold something unexpected. By the time things began to disappear, we all expected to lose. No one cared. Because we were tired. At last, we could stop trying. We could finally get some rest.

Then the end did come, and there was nothing at all.

When we vanished, we were free at last. Just Like the Stellers Sea Cow, the Tasmanian Tiger. The Passenger Pigeon and the Baiji White Dolphin. Like all those dinosaurs we’d loved so much as children. Those massive lumberers we’d once believed were smooth and gray. Neighbors who, like us, had once thought of this watery icy blue-sky place as their hometown. A place you could always come back to, if you were the type to go anywhere.

Patricia Q. Bidar is a California native, raised in the Port of Los Angeles Area. Her writing appears in a number of journals and anthologies including Wigleaf, SmokeLong Quarterly, The Pinch, Pithead Chapel, and Atticus Review, among others. Her flash piece, Over There, will appear in Flash Fiction America (W. W. Norton, March 2023). Patricia serves on the editorial staffs of Smokelong Quarterly, Quarterly West, and Barren Lit. Connect with her on Twitter (@patriciabidar) or her website (https://patriciaqbidar.com).