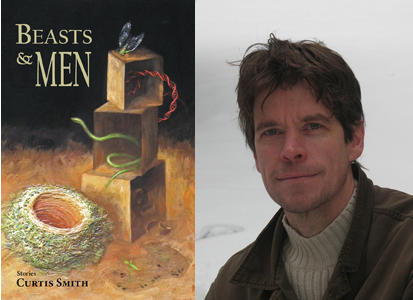

Curtis Smith’s latest books are Witness (essays, Sunnyoutside Press) and Beasts and Men (stories, Press 53). His next book will be Lovepain, a novel from Aqueous Books due in 2015.

She remembered him on a snowy day, wool cap he used to wear. ‘Thank you,’ he said before the plastic eclipsed his mouth. The bag rose and fell. Its awful rustle mesmerizing.

Monkeybicycle: Beasts & Men is packed full of stories, many of them very short. It surprised me, actually, how short many of the stories are, but as I read I discovered the power you pack within these sentences. They’re very stripped down as well, with an intense attention to detail. How important is the sentence to you?

Curtis Smith: I love the sentence. I love picking the right verb and ending with just the right image/word. For me, if things aren’t working at the sentence level, then everything else—plot, structure, conflict—falls apart.

Mb: Your writing is very focused on the exterior, without breaking narration to give us the thoughts of the characters. For me, this is perfection, and I’m often tell anyone who will listen that third person narration shouldn’t intrude on a character’s thoughts, but should show emotion and character through movement. I think this was my favorite part of your stories. Are there any rules to writing that you follow?

CS: Almost everything I write is third person (sometimes second, never first). I used to write first-person, but I don’t anymore. I still enjoy reading a good story in first-person, but it doesn’t work for me when I write. At least it hasn’t recently—but I never close the door entirely. Who knows what tomorrow will bring?

I do narrate sometimes from a character’s thoughts—but for many of these stories, especially the shorter ones, I didn’t. I wrote many of these pieces in a year-or-so span, and I kind of had this rhythm going. I found myself in tune but distant from my characters. I enjoyed that place while I was there.

Outside of trying to write a tight sentence and doing my best to respect the intelligence of my readers, I don’t think I have any hard-set rules for my work.

Mb: These are brutal stories and the unadorned nature of the language causes the violence to stick out in a very stark and menacing way. Where does this violence come from?

CS: There is an undercurrent of violence in many of the stories. I hope it’s never gratuitous or part of an easy solution to things. It’s just how I see things. I think—well, I hope—the larger undercurrent is my attempt to highlight the humanity and basic decency of my characters—even though they don’t always behave in ways decent or humane.

You lie half naked and sweating on the wooden dock. Moonless, the pond is black as the sky. Pitiless August. Crickets, cicadas, bullfrogs—the night throbs with their songs. Hands clasped across your chest, you hold a smoldering punk. The tip glows. Smoke curls toward the stars. An ashy column tumbles onto your skin.

Mb: The language and stories often have a very cinematic feel, as if each sentence describes the movement of a camera. How has film influenced your writing? What are some of your favorite films?

CS: I do often view the narrative, especially in stories where I use a more distant point of view, in terms of how a camera might view things. Of course I just highlight the items/visuals that make my point or help add to the story’s mood—so it’s kind of a selective camera.

Favorite films? Where to start? Nashville and La Dolce Vita are no doubt my two favorite films. I’m a huge fan of the movies of the 1970s. I think that’s really the golden age of film—The Godfather, The Conversation, Apocalypse Now, Mean Streets, Taxi Driver, Chinatown, One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest, McCabe and Mrs. Miller, Manhattan, Annie Hall, The Deer Hunter, Five Easy Pieces, The Last Detail, Dog Day Afternoon, Deliverance, The French Connection, Shampoo, Days of Heaven, All That Jazz. Today’s movie business, as a whole, doesn’t have the guts it did then.

Mb: “Lenin!” (which first appeared in Monkeybicycle8) is one of the longest stories in the collection and is my favorite story in Beasts & Men. It crosses a wide register, from humor to beauty to politics to celebrity and manages to stay somewhat playful even at its most serious. What was the impetus for writing a story about a child star finding new fame in a biopic of Vladimir Lenin?

CS: The story started with the idea of taking Lenin’s body on a world tour—kind of like an updated King Tut. Then I started thinking about the potential nonsense that might accompany it—the protests and angry voices. Then it suddenly appeared as a story with a whole set of random—yet ultimately united—subplots. I tried my best to give depth to each of the main characters—giving them each a chance to be vulnerable and kind yet also self-serving when it suited them best. In the end, the story’s shadiest character turns out to be its truest—at least in my view. It was a fun story to write.

Purchase a copy of Beasts of Men here, & read more from / about Curtis Smith here.

Edward J Rathke is the author of several books, one of them published [Ash Cinema, KUBOA Press 2012], two more coming out soon, as well as various short stories online and in print. He writes criticism and cultural essays for Manarchy Magazine and regularly contributes to The Lit Pub where he also edits. More of his life and words may be found at edwardjrathke.com.