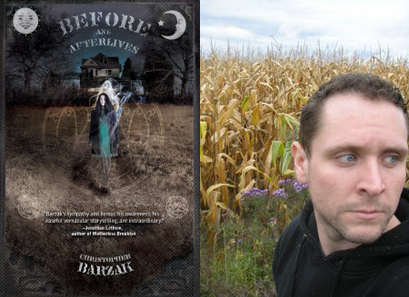

Christopher Barzak grew up in rural Ohio, went to university in a decaying post-industrial city in Ohio, and has lived in a Southern California beach town, the capital of Michigan, and in the suburbs of Tokyo, Japan, where he taught English in rural elementary and middle schools. His stories have appeared in a many venues, including Nerve, The Year’s Best Fantasy and Horror, Teeth, Interfictions, Asimov’s, and Lady Churchill’s Rosebud Wristlet. His first novel, One for Sorrow, was published by Bantam Books in Fall of 2007, and won the Crawford Award that same year. His second book, The Love We Share Without Knowing, is a novel-in-stories set in a magical realist modern Japan, and was a finalist for the Nebula Award for Best Novel and the James Tiptree Jr. Award. He is also the co-editor of Interfictions 2, and has done Japanese-English translation on Kant: For Eternal Peace, a peace theory book published in Japan for Japanese teens. Forthcoming in August 2012, his collection, Birds and Birthdays, will be published by Aqueduct Press. Currently he lives in Youngstown, Ohio, where he teaches fiction writing in the Northeast Ohio MFA program at Youngstown State University.

Monkeybicycle: Before & Afterlives covers a wide spectrum of topics, but its focus seems to be on the transition from childhood to adulthood and what that means. What was the moment you knew you were no longer a child?

Christopher Barzak: I think I realized, at least for the first time at least, that I wasn’t a child any longer when I found myself visiting one of my best friends from high school in jail at the ripe age of 18. He came from a fairly difficult and fractured family background, and fell into some bad dealings with people that were sort of living on the fringe, and ended up having to spend several months in slam as penance. I was pretty much a “good kid” type, studious and mostly kept myself in line, but I often befriended people who were my complete opposite in those ways, so doing the whole jail visit with glass between us thing was this surreal experience where, walking out of the place, I realized that my life could be taken away or circumscribed by others very easily. Somehow that recognition of life being this potentially dangerous endeavor made me start thinking about my actions and their consequences with a great amount of forethought. And later I came to think that maybe forethought is one of those skills that you acquire to become an adult, so that you’re not always living in the moment as if you have no agency, letting things happen to you and wondering why they happen to you, which I think is how it feels to be a child and young adult at times.

The thing is, even though that was a defining moment for me, I think we forget a lot of our realizations after some time has passed, and there were plenty of other moments that came later as reminders.

Mb: Community and Ohio also feature prominently, whereas your previous book, The Love We Share Without Knowing, is embedded deeply in Japan, not only as a place, but as a culture and identity. How have the places you’ve lived influenced your writing?

CB: I think I have to know the place where a story is set deeply in order to feel my way through the landscape of a story, and to be able to write authentic characters who are shaped by those places, as we all are. My perspective on life is defined by where I grew up and by the places where I’ve spent significant amounts of time living, like Japan. When I read stories or novels where place feels absent or as if the author doesn’t believe in its importance to story, I feel at a remove from the characters and the narrative. I keep wondering, where is this, why don’t they refer to the place names that mark out the boundaries of their daily existence the way we all do when we think about our own stories, or are telling a story to another person. I’m especially suspect when place is absent from a story because it’s the thing we encounter most in our lives, outside of our interactions with other people. Whether that’s a wide open and empty landscape or a hyper urban landscape doesn’t matter. Those landscapes shape us to their contours. I want to see that reflected in a story, too.

It doesn’t have to be in the mode of realism, though, which I think some people may immediately lean toward when they’re asked to think about place. There is just as much place oriented writing that occurs in fantasy and science fiction, for instance, in those made up societies and alternate worlds. And in fabulist writing, even, a good story should reflect the landscape of the dream-space it inhabits. I spend a lot of time dreaming, both daydreaming and nightdreaming, and I love to recount and write down my dreams, and I want to be able to recreate the feel of their landscapes as much as I do the “real world” landscapes I’ve lived in.

Tommy was on the dock with his easel and palette, sitting in a chair, painting Tristan. And Tristan—I don’t know how to describe him, how to make his being something possible, but these words came into my mind: tail, scales, beast and beauty.

Mb: My two favorite stories from the collection are also the longest. “Maps of Seventeen” and “The Language of Moths” are beautiful, complex, intricate, and powerful stories about sexuality, growing up, and family with incredible scenes where the fantastic erupts into everyday reality. How do fantastic or science fictional elements allow us to better understand ourselves and the world around us?

CB: First, thank you for the kind words about those stories. When it comes to the fantastic or the speculative elements that often erupt into the mundane world around us in my stories, I think those elements tend to function in a couple of ways. One thing they do, for me as a writer and hopefully for my readers, is take the internal lives of my characters and externalize them. I suppose that might be similar to the expressionist and surrealist modes in painting, where fantastical dreamlike imagery is externalized in a painting in order to speak to the internal worlds of the paintings figures. Taking the inner dream language and allowing it to speak in the outer world of the story allows for a more emotionally rigorous characterization, at least for me. Instead of saying, “He was angry,” for instance, I want to see that anger on the page in an almost fantastical way, and so I write, “The scream hangs over the mountainside like a cloud of black smoke, a stain on the clear sky, following Eliot for the rest of the day. Like some homeless mutt he’s been nice to without thinking about the consequences, the scream will follow him forever now, seeking more affection, wanting to be a permanent part of his life.”

The language of metaphor is fantastical and beautiful to me. I could say he was angry and screamed, but that just doesn’t do it, you know? I can’t feel that. Readers can’t feel that. That’s not a good rendering of what an emotion can look like, sound like, feel like. So on the level of language I like to move outside of the mundane itself.

On the more literal level of story, though, I also work in this way. So, for instance, one story is about a woman whose daughter has run away and refuses to connect with her parents any longer, and the woman replaces her daughter with a mermaid she finds washed ashore one day. The fantasy element of that story allows me to talk about this experience in a more subterranean way. I could easily have just gone through the story in the domestic realist mode, describing how difficult it is, and how mad-making it is, for this woman to be separated from someone she loves (and who she once tried to control, perhaps too much, you can see from how she treats the mermaid as she nurses it), but it’s all told slant. I guess that’s what I enjoy in a reading experience, and the fantasy and speculative fiction elements are my way into telling stories at a slant.

I also just feel like the world is something we often think we can understand, but it’s constantly surprising us. We discover the most incredible things all the time. This existence is full of wonder. Not to remark upon that wonder is, for me, a disloyalty to the true realism of this world: that it’s completely fucking awesome, and strange, and marvelous, and weird weird weird. The weird is really what happens in daily life, I think, but we tend to push it out of our range of vision after we encounter it.

Mb: Your first novel, One for Sorrow, is being made into a film called Jamie Marks is Dead. How exciting is that? Also, did you have any say on the script or casting?

CB: It’s super exciting! Like, crazy, amazing, totally whoa exciting! There’s a part of me that still hasn’t totally integrated it into my reality yet, even though I did a set visit back in March, met the director (who is also the screenwriter) and the crew and some of the actors, and saw them making several scenes. When it came to casting, no, I had no part in that. But the director, Carter Smith, had been in touch with me off and on over the several years that he held the option on the film, and I saw several drafts of the script he worked on in those years, and then toyed with some of the lines in the final script right before they started to film. I had a really special experience with Carter, I think, from what I’m told by friends who have had movies made out of their books. I think what happens is they usually buy the film rights from an author and then ignore them and do whatever they want to with the story. In my case, Carter and his crew really cared about what I thought, how I felt, and I feel close to what they’re making. I can’t imagine a better experience than that, really.

She slid the back door open, then pulled the mermaid into the house. Her tail bounced up and down as it rolled over the sliding door track. Helena took her into the bathroom, heaved her tail up and over the lip of the tub, and followed with the upper half. The mermaid’s skin squeaked against the porcelain. She ran cold water from the faucet until it splashed over the sides.

It was enough. She’d done enough. She leaned against the tub and sighed, satisfied.

Now for Paul. She would have to find a way to explain this to him as reasonably as she could. Th is was possible. This was reasonable. She had done something. She stroked her fingertips across the mermaid’s bruised cheek and decided that that in and of itself, this purple and gold blossom, would win any argument with Paul.

Mb: Before & Afterlives covers over ten years of stories. What was it like putting this collection together?

CB: It was crazy-making, to be honest. It doesn’t include every story I’ve published over that period of time, but a selection of what I think of as my best and better stories, and one of the things that was hard to do was to find the right angle on these stories that really made the collection into a collection, an exhibit of sorts. It’s a retrospective, for sure, as collections go, but I was really forced to locate the common thread between all of those stories, written over a period of nearly twelve years, I think, which can be hard. A person changes, his preoccupations change, his obsessions. And for a while I was writing stories just to write whatever I became obsessed with, but not with a collection in mind. Just the stories themselves. It took me a long time to find the common thread here, and it’s embodied in the title itself, Before & Afterlives. These are stories about life and what comes after life, in some cases, and in other cases it’s about the lives that come after a person has shed their skin and become another kind of person (sometimes literally, in the case of one story). Like any great struggle, though, once I found the perspective I needed to arrange the collection into its final form, I felt a great relief. And with that great relief, a familiar feeling of being ready to move on to my next life as a writer began to appear. I’m really looking forward to discovering what I write next. ;-)

Purchase a copy of Before & Afterlives here, & read more from / about Christopher Barzak here.

Edward J. Rathke is the author of several books, one of them published [Ash Cinema, KUBOA Press 2012], two more coming out soon, as well as various short stories online and in print. He writes criticism and cultural essays for Manarchy Magazine and regularly contributes to The Lit Pub where he also edits. More of his life and words may be found at edwardjrathke.com.