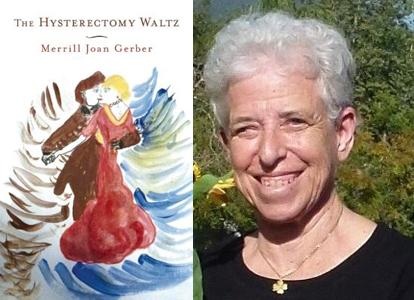

Merrill Joan Gerber is a prize-winning novelist and short story writer. Among her novels are The Kingdom of Brooklyn, winner of the Ribalow Award from Hadassah Magazine for “the best English-language book of fiction on a Jewish theme,” Anna in the Afterlife, chosen by the Los Angeles Times as a “Best Novel of 2002” and King of the World, which won the Pushcart Editors’ Book Award. She has written five volumes of short stories. Her stories and essays have appeared in The New Yorker, The Atlantic, Mademoiselle, The Sewanee Review, The Virginia Review, Commentary, Salmagundi, The American Scholar, The Southwest Review and elsewhere.

Her story, “I Don’t Believe This,” won an O. Henry Prize. “This is a Voice From Your Past” was included in The Best American Mystery Stories.

Her non-fiction books include a travel memoir, Botticelli Blue Skies: An American in Florence, a book of personal essays, Gut Feelings: A Writer’s Truths and Minute Inventions and Old Mother, Little Cat: a Writer’s Reflections on her Kitten, her Aged Mother . . . and Life.

Gerber earned her BA in English from the University of Florida, her MA in English from Brandeis University and was awarded a Wallace Stegner Fiction Fellowship to Stanford University. She presently teaches fiction writing at the California Institute of Technology in Pasadena, California. Her website is: www.its.caltech.edu/~mjgerber.

Monkeybicycle: This is the first novel, or probably any work of art, I’ve encountered that deals with a hysterectomy. It was shocking for me to read these things I had long assumed were true being turned not only upside down, but inside out. How do you think art opens the world to us?

Merril Joan Gerber: I think the social milieu has to be ready for a work of art for it to be instructive and illuminating. The Hysterectomy Waltz was written thirty-three years ago—but the world was not ready for it. It was too early for its time, then—although several publishers (as so often happens) had ideas for changes that would render it (in their minds) “publishable.” So I followed their suggestions, one by one—sometimes working for weeks, sometimes for months, on making the suggested changes, till they each told me, as publishers do, “thanks, but that’s not exactly what I had in mind. I’m just not in love with this book. Good luck elsewhere!” Finally, it seems, this subject can now be discussed openly, and its time has come.

‘But a girl has to wait all her life,’ I pleaded. ‘A girl has to wait for breasts, wait for periods, wait for dates, for proposals, for labor pains.

‘What else is there to do?’ said the old sage, who in truth was my Jewish aunt. ‘You can always make a pot holder while you wait.’

Mb: The medical experiences are truly horrifying and aggravating. Has this been your experience with the medical field?

MJG: Though writers are often asked how much of a piece of fiction actually happened to them, the question can’t be answered. Every novel is a combination of observation, experience, imagination and magic—and often when a writer has finished a book, she can’t even recall the factual basis (if there was one) for the scenes she has written. Thirty-three years ago, most gynecologists were men—today, thank heavens, there are many women in the field with a more open and generous understanding of what hysterectomy involves.

Mb: The Hysterectomy Waltz is painful, hilarious, and even beautiful, sometimes all at once. Even the title ties this beauty to the act, and I think that’s only possible through the consistent sense of humor. What is the role of humor in your life? How does it allow us to cope and overcome?

MJG: Humor makes possible the ridiculous reality of life’s ordeals. At the same time a writer is suffering in the reality of a situation, some part of her sees the utter lunacy of what’s happening—and she is driven to express it in satire.

Nearly everything in The Hysterectomy Waltz is “grossly exaggerated”—that’s what satire is: “holding up human vice to ridicule, often using burlesque, caricature, wit, farce, derision and mockery.” I hope I’ve got all of those elements in my novel.

‘But what’s the mortality rate on something like this, or is it the morbidity rate?’

‘Why worry in advance?’

‘I have three daughters.’

‘I have three sons. Maybe we can make a shidukh.’

‘If I live, we can give them a triple wedding at the Beverly Hills Hotel. Does that tempt you to allow me every margin of safety? Will you use your special connections?’

‘Don’t worry, you’ll live.’

‘How long?’

‘Don’t ask.’

‘I have to ask,’ I sad, beginning to cry.

‘Don’t cry,’ she said.

‘I have to cry, it’s involuntary.’

‘How can I cheer you up?’

‘God knows,’ I sobbed. ‘You also owe me for the day we missed the movies.’

‘I know,’ she said, ‘I’ve always felt bad about that. Let’s try to remember the important things, though. Our shared memories. The sun shining though the trees at Girl Scout camp. In fact, let’s sing our camp song together.’

Mb: Much of the novel deals with the expectations and assumptions of men about women. And while this works as a critique, it never feels that way. It’s a very easy novel to read and quite entertaining, but still powerful. Just as there are expectations of men about women, I think there are expectations about literature when it includes real entertainment. What are your thoughts on these? On how men perceive women and how people perceive entertaining literature?

MJG: I’m glad my novel is entertaining. I laughed out loud while writing it, and though it may exaggerate and sometimes make fun of the relationships between men and women, it’s meant to be an appreciation of love, sex and marriage.

Mb: Did any of your children become doctors or marry doctors?

MJG: No, but I wish they had. When I was a young mother I often wished I had married a doctor so that when my children had croup, or high fever, or were choking on a cookie, a doctor in residence would be there to save their lives. I still think every mother should be licensed as a nurse-practitioner during her first pregnancy. It would prevent a world of worry if we knew basic life-saving procedures and could make some practical diagnoses about fevers, earaches and bumps on the head.

Purchase a copy of The Hysterectomy Waltz here, & read more from / about xTx here.

Edward J. Rathke is the author of several books, one of them published [Ash Cinema, KUBOA Press 2012], two more coming out soon, as well as various short stories online and in print. He writes criticism and cultural essays for Manarchy Magazine and regularly contributes to The Lit Pub where he also edits. More of his life and words may be found at edwardjrathke.com.