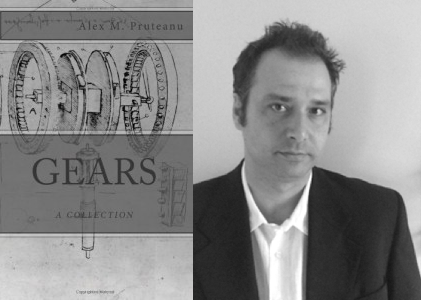

Alex Pruteanu is author of novella Short Lean Cuts and Gears, a collection of stories from Independent Talent Group. He has published fiction in NY Arts Magazine, Guernica Magazine, Pank Magazine, Specter Literary Magazine, and others. He is currently working on a novel titled The Sun Eaters. He lives with his family in the Triangle area in North Carolina.

Monkeybicycle: Gears is a brick of a book and it’s your first collection. Most first time collections by writers tend to be under 200 pages, and probably closer to 100. What made you decide to dump so much into this one?

Alex Pruteanu: During the years 2011-2012 I got to work pretty diligently, blackmailing, extorting, and outright threatening editors with extreme violence (kidding . . . sort of) and ended up publishing in a few dozen literary journals. I wasn’t originally going to even entertain putting together a collection, but as I looked over the material that had been published over 20 or so months, it became clear that a cohesive body of work existed; there was a common subject and sometimes even voice running through many of the stories collected. I thought it wouldn’t be fair to not have them all live under the same roof. Most of Gears is comprised of published material, but I also wrote a handful of short stories just for the book; stories that I wasn’t interested in shopping around to anyone. I thought readers deserved some new material peppered in with published stuff. Readers always deserve something new. They always deserve to be propelled forward by a writer with each new work. I feel that if there is nothing dynamic or progressive with new material, then it’s time to hang it up and go mow the lawn, trim the hedges, take out the garbage, and wait anxiously for tomorrow’s pizza coupons delivered to your mailbox.

Mb: For all its diversity, Gears feels like a cohesive work. It all feels like Alex Pruteanu, whether it be poetry, prose, or somewhere in between, something else. How much does the form influence the piece, or how does the idea behind the piece influence its form? How important is the relation between form and content to you?

AP: Yes, in the foreword of the book I outline how the collection is held together thematically: each little story working as a gear within the larger system, which is the Machine….the book itself. Most of the stories in Gears deal with some type of movement, whether physical or metaphorical or philosophical, even if perceived by a character.

The piece or the idea behind the piece greatly influences form for me, especially if I am writing short, flash material. With flash, there isn’t much time to lay out much of anything; my aim in flash is to take the reader into a usually fucked up, disorienting, most often savage situation, present it, and leave him/her there to make a choice. Rather, what I mean is, leave the scene un-resolved, letting the reader conclude or resolve whatever he/she wants. I hope that the reader brings his/her own experiences to the story and makes a choice; the more moral and difficult the choice, the better.

The material dealing with fluid, rapidly changing, urgent situations, I tend to write in simple, almost staccato-like language: the fewer adjectives the better. I want the language to read choppy, but still communicate emotion. This is something that I learned from reading and studying Hemingway and Gertrude Stein when I was a teen. Stein’s experiments with language in particular are fascinating to me, even to this day. Hemingway’s ability to bury emotion and backstory under what seems like very simple language is extremely hard to emulate. Although Papa’s work doesn’t hold for me anymore at my age, I am grateful for his contribution to language and to the mechanics of writing simply but with a ton of emotion.

There are flash stories in “Gears” that are written in a more classical, literary way—those tend to stretch to longer word counts but still hold the “flash” label. With those, I feel I have more time to develop not just themes, but the layout of the language, as well. I feel now, in the middle of writing a novel, that I have the time and latitude to truly look at all angles of this beautiful art we call “writing” and fully develop each aspect of it as I see fit for the particular story. Initially a novel seems intimidating, but in reality it allows for everything a writer wishes it to be, whether something small, compact, tight, or sprawling and wide and all-encompassing. Writing a novel opens up a gamut of emotions within a writer; everything from rage, hate, disgust, to contentment and kindness and acceptance.

I’m no saint. I’m no sinner either. Just the worst possible human being you can imagine: I’m bored.

Mb: You immigrated to the US from Romania, leaving the autocrat Ceausescu behind and entering into the Reagan years. How did these experiences influence not only your life, but also your writing?

AP: Our household was politically hyper-aware, mainly because we were political refugees (from a Communist regime), but also mainly because my parents were very much pro-U.S. (pro-Reagan), and it was almost considered a duty, a part of our new, free life to be well-informed politically and socially. We owed it to this country.

I grew up eating dinner at 6:30 while watching/listening to Frank Reynolds (ABC News Tonight) first, then Peter Jennings after Reynolds died. My parents, as mentioned, were very much pro-Reagan but they didn’t particularly push political views on me; they spoke their minds, but they never pushed me into agreement. I didn’t disagree, either, necessarily. I was 11 so I just kept my mouth shut and listened and learned. My parents didn’t particularly push anything on me after age 11; they were too busy working long hours at shitty jobs, and that actually worked to my advantage. From not really being given any kind of direction, I learned to listen closely and to think for myself. My parents are also quite religious, but again, nothing was truly ever pushed on me. I am a staunch atheist, but not because of any kind of backlash against years of being told what to think . . . in fact, because I learned to formulate my own opinions, and my decision when it came to religion was to not embrace any of it in any kind of form.

My writing is often infused with shades of politics, more so the stories that take place in Eastern European countries, but also the ones set in America, as well. I wouldn’t say I wish to drive home a particular political or social message in my work, but I do tend to write about the working class, the disenfranchised, and the people who seem to be oppressed by any sort of lecherous system. But honestly, it’s not for some valorous, heroic type of reason; this is simply the working class in which I grew up and know well. I don’t write about things I don’t know. I make up things but I don’t make up things.

Mb: You’ve had many jobs in a wide variety of fields, and I find this kind of variety present in your fiction. A mix of philosophy, savagery, despair, politics, and life, typically from the perspective of an outsider. Was writing ever the goal, or just where you landed?

AP: Writing is where I landed because of all the reading I did early in my life. I grew up loving to read, and I’ve carried that through into today, although today I am much more discriminating of what I choose to read. I did my time reading awful examples of fiction and feel I’ve learned from all of them accordingly. Nowadays I’m extremely picky of who or what I choose to read.

Originally I was interested in making documentaries and films, as a teenager. I went to university, and, although my degree is in Communications, really the concentration of my education is in film and cinematography. Within the curriculum there were screenwriting classes, so those buttressed up the desire to write, particularly dialogue. I was, and still am, enamored of well-written, sharp dialogue. I never ever thought about “being a writer.” I wanted to make films. I was also a motivated budding musician and very much wished to make a living playing music. Among all of those desires, writing came naturally and almost seamlessly. Films made me pay much attention to writing/dialogue, which led to being interested in plays; I love advancing story via dialogue only.

You’re right in your attentive comments describing the potpourri one finds in my stories; those are all things in which I’m interested, so they appear often in my work.

We ran together on the frozen land like a pack of insane hyenas. Children. All ages. Starving. Poor. Ill-dressed. Some dying from tuberculosis. Others living with pneumonia, coughing up liquefied guts and bile. We puffed on used, dry butts we found in the rubble of the war. Stained, finger-rolled, half-smoked cigarettes; some abandoned in a hurry, others interrupted by sudden death. All tainted by once-infected lips. Herpes. Blisters. Cankers. Remnants discarded by the dead. We made up games and stories, all the while subsisting in the shadows of destruction, orphan concrete, rebar, and petrified bones

Mb: You’ve published a novella, Short Lean Cuts, and now a short story collection. When’s the novel coming?

AP: I don’t know when the novel will be published. Presently it’s about 2/3 of the way written and there is one hopeful iron in one particularly important fire regarding its publication, but the percentages don’t look too good historically, so I don’t hold much hope. The book is called The Sun Eaters, and it’s the simple story of two brothers, ages 14 and 9, somewhere in an unspecified Eastern European country in the years just after WWII, trying to survive weather, food shortages, and the changed political ideology of the time. It’s not a lamenting story of hardship and difficulty, it’s more a tale of a particular slice of the unforgiving world as seen through children’s eyes. I’ve taken great care to write this book more in a poetic, “classic literary” fashion . . . this may be something that might turn off some modern readers, but it doesn’t concern me if people base their reading choices on stylistic details instead of story subject. The story, I believe, is truly honest and emotional and quite great, and I’ve chosen to present it in the opposite way of the experimental style Short Lean Cuts carries.

I can tell you that whenever (if ever) this book is published, I will have long moved on to my next idea and project. Short Lean Cuts was written in 2007 and published in 2011. By the time people read the little book, I was so far away from it that it almost felt new again to re-read.

Read more from / about Alex Pruteanu here. Buy a copy of Gears here, and Short Lean Cuts here.

Edward J. Rathke is the author of several books, one of them published [Ash Cinema, KUBOA Press 2012], two more coming out soon, as well as various short stories online and in print. He writes criticism and cultural essays for Manarchy Magazine and regularly contributes to The Lit Pub where he also edits. More of his life and words may be found at edwardjrathke.com.