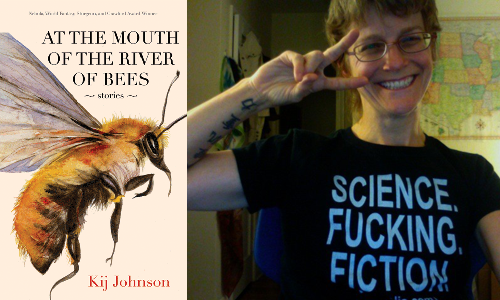

Kij Johnson’s stories have won the Sturgeon, World Fantasy, and Nebula awards. She has taught writing and has worked at Tor, Dark Horse, Microsoft, and Real Networks. She has run bookstores, worked as a radio announcer and engineer, edited cryptic crosswords, and waitressed in a strip bar.

I am not an unreasonable man, said I:—If she apologize for her contumacity, for subverting all my plans and desires, and for her importunate demands on my pocketbook, time, and person, I shall most willingly forgive her, and she shall pass from this world with her conscience cleared of these sins.

Monkeybicycle: Covering over 20 years of publications, how did you go about picking which stories to include in At the Mouth of the River of Bees? What was it like looking back at some of the older stories, such as Wolf Trappings, which is nearing twenty five years old?

Kij Johnson: Much of the selection process was very simple: Am I proud of this story? I didn’t think much about theme, but I write a lot about the human/animal interface, and that became a spine of sorts. Picking a few older stories was hard because I’m generally less satisfied with my work in the past, but I felt that a couple of them belonged—they were all about how animals and people connect, and the difficulty of bridging the gap between the self and the Other. I rewrote them a little, but I was trying not to polish them out of all recognition. They were early work; they probably should stay a little rawer.

Mb: This is an incredibly diverse collection, which I find to be a huge strength. It captures many different modes and styles, while remaining consistently humorous, which was another delightful quality. I often find that story collection lean towards deep darkness. How important is it for writers to have and/or display a sense of humor?

KJ: I don’t think of most of these stories as being humorous at all, but you are not the first person to have said this so I’ve put some thought into what you all mean. My best guess is that it comes from a sort of wryness that sneaks in no matter what the voice or style or topic, something that might be encapsulated as, “Huh.” Life is full of strange things, and we can decide how to deal with many of those things. My choice is to be bemused.

Mb: Ponies, despite what I said in my previous question, is a harrowing look at childhood and acceptance. How does the fantastic illuminate reality for us? What can speculative fiction do that realism can’t?

KJ: “Ponies” is in part about the ways little girls in the West brutally define and enforce social norms for one another. It would be very possible to write an entirely realistic story about this, but to my mind, there is a virtue to the fact that I can explode the damage caused by the process into something visceral and shocking. Fantasy and science fiction give us a way to push something to its uncomfortable, illogical extreme, forcing the reader to engage—or to reject the story. But because of the wonderful mobility of symbol, the way a metaphor can be made real, the story has other interpretations and broader applications.

Later that night, back at the bus, Geof says, “Wherever they go, yeah, it’s cool. But see, here’s my theory.” He gestures to the crowded bus with its clutter of toys and tools. The two tamarins have just come in, and they’re sitting on the kitchenette counter, heads close as they examine some new small thing. “They like visiting wherever it is, sure. But this is their home. Everyone likes to come home sooner or later.”

”If they have a home,” Aimee says.”Everyone has a home, even if they don’t believe in it,” Geof says.

Mb: You’ve had many different jobs in various fields, but have also taught writing and been an editor. How have these experiences shaped and/or changed your writing?

KJ: I believe that most writers benefit from novelty, and the odder the better. Anything that brings new information or insight is good: people you would not otherwise know, unfamiliar arts or crafts or trades; novel ways to organize information or experience; unknown settings or situations. Working in comics, games and technology were all good ways to see story differently. I have expanded my understanding of people by working with advertising people and strippers, among others; my hobbies have taken me into regular company with people who live in their vans and civil engineers. And of course, publishing was great for teaching me how to get published!

Mb: At the Mouth of the River of Bees is your first book in several years. What are you working on now, and what’s coming out next?

KJ: I am working on a very long, very complicated novel. I wanted to do something that would be a stretch, so it has a large cast of characters and a lot of things happening; one of the points of view is that of a man; it’s set in a place I didn’t know much about, Central Asia; and the voice is quite rigorous. I am hoping to have a draft by the end of the year. I am also deciding what to do with an odd little collection of flash pieces called “The Apartment Dweller’s Bestiary.”

Read more from / about Kij Johnson here. Buy a copy of At the Mouth of the River of Bees here.

Edward J. Rathke is the author of several books, one of them published [Ash Cinema, KUBOA Press 2012], two more coming out soon, as well as various short stories online and in print. He writes criticism and cultural essays for Manarchy Magazine and regularly contributes to The Lit Pub where he also edits. More of his life and words may be found at edwardjrathke.com.