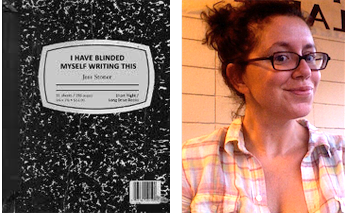

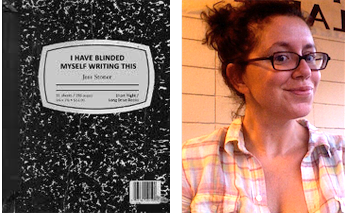

Jess Stoner is the author of the novel I Have Blinded Myself Writing This from Hobart’s Short Flight / Long Drive Books and the choose-your-own adventure poetry chapbook You’re Going to Die Jess Wigent from Fact-Simile. Her book reviews, poems, essays, and short stories have been published or are forthcoming in Necessary Fiction, The Rumpus, Two Serious Ladies, Alice Blue Review, Super Arrow, and other handsome journals. She earned her Ph.D. from the University of Denver and now lives with her linguist-of-rollerblading husband, Frank, in Austin.

Monkeybicycle: Let’s start with Hobart’s brilliant design of your book. I Have Blinded Myself Writing This is published in the form of a composition notebook, complete with marbled cover, rounded edges, and sans page numbering. How did this design come about?

Jess Stoner: The image is a scan from one of my own, personal notebooks. Aaron & Elizabeth had the idea of making the title how it is on the cover and they did the rounded corners. I love it so much. The book, from the moment I began thinking about it, was always meant to be an object, something the narrator, the mother, was writing for her daughter. I really wanted her to give it to her daughter, like, for real. Because she wanted her daughter to know the things she knew before she forgot them, or before she made herself forget them. When I was in the writing of it, after a few months, I was like: I’m going to handwrite all of these pages, because that’s how much I want this to seem like a personal artifact. I let myself have that moment of pretention, and then got off my own high horse—I think the balance of the personal artifact and the published book is much more intriguing.

Mb: The book is focused on memory loss and time, how a child growing up becomes a grown-up with a child, worrying about a child growing up. Have you always been concerned with, and writing about, how much anyone can (or should, or could) possibly remember?

JS: All of these kinds of thoughts came to fruition because my beloved maternal grandfather moved quickly from Alzheimer’s to dementia and then died while I was writing the book. At first, jesus, it was so terrible. As the disease progressed, I think my mother could only stay sane by rationalizing it, by telling us that my grandfather was gone. That her father was gone. Because his memory was gone. One of the things that was most discomfiting about this kind of horror was that this was the first time I ever glimpsed my mother as the child, the daughter that she was. I was grown-up enough to recognize her as her own person, and also a wife and a mother. But during these few years, she was trying to protect not only her father, but the memory of her father, even as he was still living and breathing and running away from his assisted living apartment and was convinced he was going to be hung from the trees outside his room.

As my grandfather lost his memory, my mother became this kind of ghostimage of who she was a girl, trying desperately to hold on and push her father away at the same time. I was so lost, as to what my place in this situation was. I became obsessed, for the first time, with the fact that I was a daughter, and that my mother was a daughter. I know that sounds super-simple and stupid, but it was almost cripplingly emotional to me. During certain terrible moments, I know my mother needed to be comforted not as a mother, but as a daughter, and comforting my mother, as a daughter, was bizarre, and forced me to get over my own shit and refocus, although I’m pretty sure I failed because I’m still bewildered by the idea that my mother is a daughter, that we are the same in some way.

Mb: I Have Blinded Myself Writing This uses numerous brain diagrams as well as detailed descriptions of brain locations and their functions. How much of this was knowledge you already owned, and how much is due to research you conducted?

JS: I have a hard-on for research. All I want to do is research. So much more than write. I just want to go from one weird connection to the next and live in those connections and scholarly articles and not have to put them together to make something and just gather and gather and gather everything I find forever. The research was my favorite part of the book, although that might be a little bit because it was safer and less emotionally draining, but I loved digging into the brain. I am obsessed with areas of science that are unknown and maybe can’t be known—human phenomena that resists human comprehension. And that’s what drew me to memory, the study of it, how much we don’t know. I used this novel as a part of my dissertation at the University of Denver, and in one page of the book, the research I used was from a member of my dissertation committee, the wonderful Dr. Janette Benson. She researches, among other things, cognitive development in infants. And the part I stole from her was when Teddy mentions that his daughter is learning what yesterday and tomorrow mean. If I was still in school and had access to academic journals, I would probably forget to finish this answer and would read like seventeen articles about what it means to be conscious of time and space, of yesterday. I’m a junkie of all things new and outside of the limits of my learning, things I really have no right to talk about although I always want to talk about them. It makes me feel alive and new in the world.

Mb: “What if our memory could be mapped? These pages. See them as a road atlas. Latitudes of previous breaths.” If your memory was a map, where would it lead?

JS: The only way to begin this answer is to explain that my husband calls me a pre-Vulcan. I am the kind of people who cannot suppress their emotions. I feel like my memory would be a heat map and this map would “lead“ only to a series of red and less red colors. I feel like I don’t even have memories so much as I have these imprinted heat feelings. Almost all of this map would be heat map of my embarrassments. I live in a state of constant embarrassment. I still remember having this kind of manic moment in 1st grade, and doing a handstand in class and having my name put on the board, 26-years later and I’m still embarrassed. I remember in 4th grade, when one of my teachers told us her fiancée had been killed when he was struck by lightening on a golf course and I started crying like an idiot. I remember when my family moved to Oklahoma and Texas and back to New York and all the ways I embarrassed myself in the months after those moves. I remember all of my broken hearts like they just happened. I remember the boy I loved in 8th grade who gave me my first kiss during the movie Passenger 57, his mother was my dental hygienist. I remember what it felt like and know what color it would be on the heat map because I also remember what I was wearing and how embarrassed I was to be wearing glasses and couldn’t figure out what to do with them because I had no idea what to do with my tongue. I remember every doltish thing I have ever done. I remember every dumb thing I ever said during classes at the University of Denver that showed that I wasn’t nearly as smart as my incredibly intelligent classmates. I used to say that I wanted to have a tattoo of a knot done on my wrist, so I would remember to stay knotted up, instead of unspooling, in a sea of heat and blushing remorse because I opened myself up. A heat map is definitely the only way to do my memory map. All these spikes, super-red spots, even in my dreams, where I also embarrass myself. Tufte has to have a way to do this, to represent visually the progression of a life through a series of regretful blushes.

Mb: “It turns out everyone has amnesia. None of us knows who we were before we were four. It’s infantile: we can’t describe with words events that occurred in our lives before we knew the words to describe them. This makes it seem that words are why we have memories.” What is the youngest word you know, or the word you’ve known the longest?

JS: I can’t remember a word. I can remember, very specifically, and I must’ve been four or five, singing along with my father to Simon & Garfunkel’s “Patterns” from Parsley, Sage, Rosemary, and Thyme, I was tiny with my curly hair (which my parents called my “Tina Turner” hair. back then (I’m so glad I am alive when I’m alive so my hair could’ve been called that)) and as I crawled up my father’s legs, I shouted with him “THE RAT DIES.”

Purchase a copy of I Have Blinded Myself Writing This here, & read more from / about Jess Stoner here.

J. A. Tyler is the author of nine novel(la)s of poetic fiction. His work has been published in Black Warrior Review, Redivider, Cream City Review, Diagram, Fairy Tale Review, Columbia Poetry Review, and New York Tyrant. He also runs Mud Luscious Press.