Reviewed by Dan Coxon

Building Stories, Chris Ware

Pantheon

ISBN-13: 978-0375424335

$50.00, 260pp

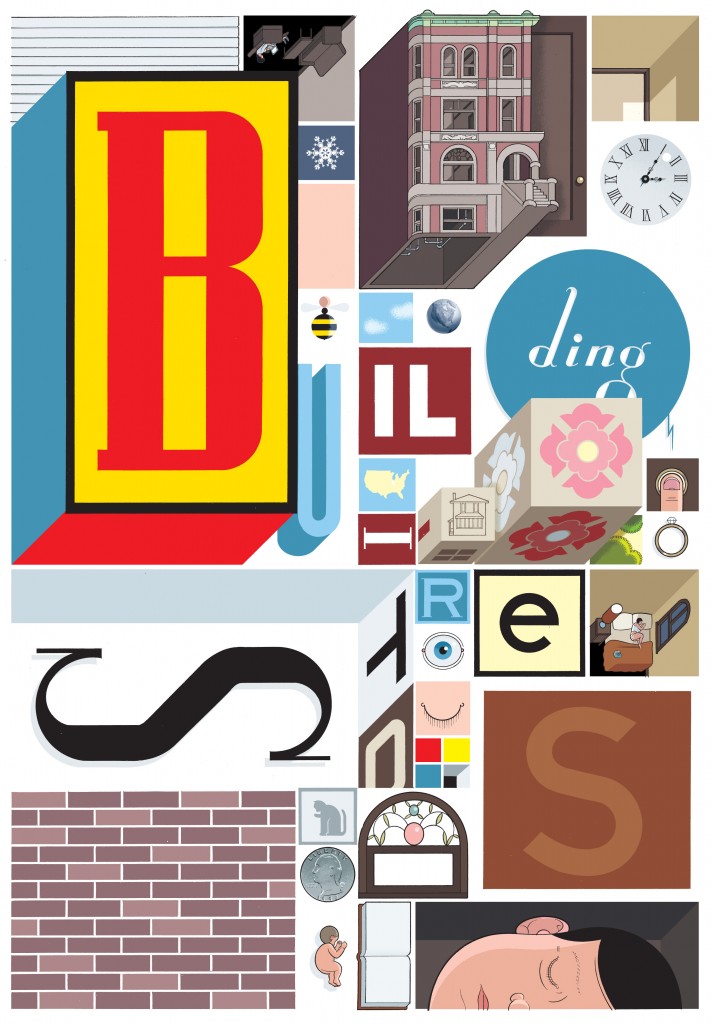

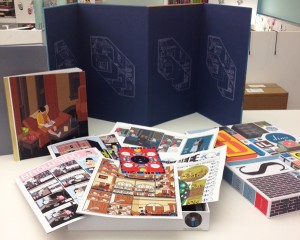

Chris Ware’s latest graphic novel isn’t a book. It’s barely even a novel. Building Stories is a boxed collection of fourteen “distinctively discreet Books, Booklets, Magazines, Newspapers, and Pamphlets”: a story that’s been deconstructed and presented as a build-it-yourself narrative kit. There are no guidelines on where to start, or where to end, or even on how to approach the box’s chaotic jumble of reading material. Some of the books feel like graphic novels in their own right. Two of the pamphlets are so slight they might almost be oversized bookmarks. One of the items is a large folding piece of card with text and illustrations across one side, like the board for a frustratingly complex board game. Whether this particular item is supposed to be a book, a booklet, a magazine, a newspaper, or a pamphlet is unclear.

The effect upon opening the box is dumbfounding. Most of us have no experience of reading narratives this way and you can’t help feeling nervous as your hand first fumbles inside. You want your experience of Ware’s world to be as wonderful and as engaging as possible. You fear that if you choose unwisely you may ruin your enjoyment of the narrative forever. The natural inclination is to take the first item from the top of the pile, but as they are packaged in ascending order of size, that means starting with the smallest pamphlet. Those two large, hardback tomes beckon.

The freeform nature of Building Stories‘ narrative is not without precedent, but it’s unique enough to make the reader pause. B.S. Johnson’s The Unfortunates was published in 1969 as a box of loose chapters, with the first and last chapters specified, but the rest to be selected by the reader at random. In 2005 McSweeney’s released their quarterly journal as a box of found objects, although these were never intended to be read together as a single narrative. We’re more familiar with authors doing the structural work for us, and without a conventional linear narrative – or even a clear starting point – embarking on Ware’s graphic novel is daunting and loaded with consequence. The possible permutations are innumerable.

For those confounded by choice, one of the larger books is a good place to start. The gold-spined book (in the style of the Little Golden Books) follows an unnamed female protagonist through an eventful day in her largely dull and mundane life. Compared with some of the other items in the box this reads as a conventional narrative: she has a bizarre sex dream, loses her cat when the building’s handyman comes to mend her toilet, then reconnects with an old friend. The protagonist features heavily in the box’s other stories too, and her hard-knock life – filled with failed relationships, crushing disappointments, and a childhood accident that leaves her with a prosthetic leg – gives Building Stories much of its melancholy tone. As she contemplates suicide she tells herself “I’m never going to meet anybody who will love me”, while examining her “disgusting bloated body”. Ware isn’t inclined to happy endings, and there are very few happy beginnings either.

The other characters, a collection of misfits and failures who occupy a single tenement building, echo this maudlin tone. There’s the aging landlady, who has already experienced the kind of tragedy that the other characters only worry about; the ill-matched couple downstairs who constantly argue and bicker; the handyman who used to live in one of the apartments, his sagging jowls and sad eyes telling you all you need to know about his life. Nobody gets out of this building – or this life – without scars. There’s also Branford the Best Bee in the World, a cartoon character invented by our heroine. Branford offers an easily digested echo of the book’s major themes as he faces derision, self-doubt, and the fear that he is “an impure, disgusting slug who thinks too much of fertilizing the queen”. His story is clearly indebted to traditional comic strips, but Ware still imbues it with crippling existential doubt.

And then there’s the building itself. Ware has a theory that physical spaces influence both our moods and the structure of our lives, and Building Stories takes that concept to the logical extreme. The tenement building has its own voice, rendered in italics, occasionally interrupting the stories or offering soliloquies on the tenants who have passed through its rooms. It rarely influences the action, but there’s a sense in which it becomes a theatrical narrator, commenting on the characters and acting as a conduit between the reader and the depicted events. Even Ware’s artistic style reflects his fascination with the architectural, telling his story through simple geometric shapes and well-defined lines. The rooms are clearly delineated in three-dimensional space. The characters are blocky but solid, and often distressingly real. The overall effect has more in common with an architect’s conceptual drawings – or a Lego manual – than your average graphic novel.

Building Stories isn’t an easy read. The experimental format can be distracting. The lack of a clear narrative leaves the reader to do much of the work. Then there’s the subject matter: a seemingly endless parade of failures and disappointments that can appear crushingly pessimistic. But it’s in Ware’s empathy and humanity that he distinguishes himself, and you’ll find yourself drawn back to his nameless characters time and time again. Not because they entertain or excite us, but because they seem so effortlessly real, and so thrillingly alive. As for where to start and end your journey, Building Stories has one great advantage over real life: you can dip back into the box and experience it a million different ways. Just don’t expect any of them to end happily.

Dan Coxon is the author of Ka Mate: Travels in New Zealand and The Wee Book of Scotland. His fiction has appeared in the anthology Late-Night River Lights and in numerous small press magazines and journals, and he is a regular contributor to The Nervous Breakdown. He currently lives in the Pacific Northwest, where he spends his spare time looking after his newborn son, Jacob, who offers more plot twists than any book. Find more of Dan Coxon’s writing at www.dancoxon.com, or follow him on Twitter @DanCoxonAuthor.