Reviewed by Ariell Cacciola

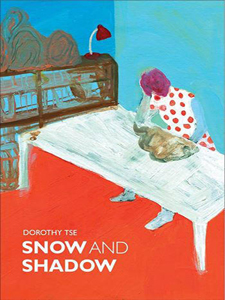

Snow and Shadow, Dorothy Tse, Translated by Nicky Harman

East Slope Publishing

ISBN-13: 978-9881604606

$18.00, 212 pages

For surreal fiction to work, the writer must have confidence. No matter how fantastic the images and situations, it always comes back to confidence. The reader should not sense the author’s doubt in either prose or content. The best works of magical realism flood forward on the page like an endless ribbon being pulled, and this is so apparent in Hong Kong writer Dorothy Tse’s newest short story collection, Snow and Shadow.

Each story is constructed out of “cool sentences,” as translator Nicky Harman notes in her introduction to the collection. Tse is not concerned with ornamental language, and the reader is lulled forward with prose free of stuffy word choices, leaving an exactness that evokes a world sometimes similar to our own, which then becomes a world populated with often nightmarish scenarios.

Almost all of the stories are set in some sort of urban space: tightly packed apartment buildings, hospitals, busy streets. It is only the final and titular story, “Snow and Shadow,” that finds itself apart resting in a world concerned with emperors, imperial guards and the like. But the story still feels consistent with the other stories, for it does not escape Tse’s fantastic eye.

Instead of expected and ordinary names, Tse calls her characters Tree, Leaf, Knife, Wood, Recall, Memoria, or the more Kafkaesque, K and J, shifting focus from the specificity of names. They are all individuals, but it is often less about them and more about how they relate to other characters, with many of them offered as dichotomies or reactions to others. In “Head,” a family awakens to the mysterious disappearance of the son’s head. Like all good magical realism, the story is not about the explanation of the circumstances, but how the world operates within these fantastic terms. The images are stark right from the beginning as the son, Tree, is led to an ambulance, headless, not at all an unusual predicament in Tse’s stories.

Hospital beds and wheelchairs whizzed back and forth, many of them occupied by patients who had lost noses, limbs, hearts, and other organs…he came to a decision: he would donate his own head to his twenty-five-year-old only son.

The father, Wood, donates his own head, transforming the story into an examination of a father’s passion for his son without abandoning the more surreal elements. What we get is a pseudo-family history going back before the birth of Tree in 1977. Wood becomes obsessed with his unborn child, often drawing his wife with the shape of a fetus growing inside her. When asked who he is drawing, he pulls out a photograph of himself and says, “I’m using this. That kid’s going to be the spitting image of me.” This statement is a familiar one between parents and children, but it becomes bizarre in the capable hands of the author. The transplanted head still retains the face of the father. It is not quite grotesque, because it is encapsulated in a magical realistic world, but it could be argued that it is toeing the line.

Not all thirteen stories of Snow and Shadow are composed of lopped off heads and transformed bodies. Some are dreamlike and give the feeling of a hand running through water leaving swirls and ripples around it. “The Mute Door” recalls non-existing doors that mimes construct out of waves of their hands in the air: The door is constructed in such a way as to conceal the fact that it does not exist. The idea is introduced so aptly and can be applied not only to the story, but to the collection as a whole. Smells, emotions, and occurrences are identifiable in Snow and Shadow, yet they reside in a dream—or nightmare, in some cases. A pizza delivery man is labelled a stranger when he comes to the Displacement Apartments in “The Mute Door,” but like the residents, once he enters the building, he can’t quite find the right door. Reminiscent of Kafka’s unbreached castle, the apartment building is so perfectly name Displacement and no matter how hard they try, the residents just can’t find their way to the correct front doors. Many even pack suitcases to take with them whenever they leave home, so upon their return when predictably they are unable to find the correct door, they have novels and laptops to keep them company in the bustling corridors.

[F]or the residents, the apartments are like face-down playing cards on a table top, moving around, taking their doors with them, in a completely random way. That is to say, when the residents leave their apartments, they have to go through the process of finding them once more, with no rules to follow.

Like the residents of the Displacement Apartments, there are no rules to Snow and Shadow. The unexpected is king and explanations are uncalled for. Turning into a fish or actors’ tears becoming bees and centipedes are par for the course. Lovers might hack off their own limbs for each other, but I would have it no other way. Their wounds linger on the reader’s mind like thick brush strokes.

Nicky Harman does an excellent job translating Tse’s stories. They stand alone, but together build a hypnotic trance, each sentence rendered with a sense of grace and sparseness. The images and actions are left on their own, not muddied by a heavy hand.

The stories within Snow and Shadow build on each other with every new page. They are blunt, stark, and nightmarish, and this is what makes them all so exquisite. Through Harman, Dorothy Tse’s collection manifests an individual voice in a world overflowing with the unexpected.

Ariell Cacciola is a writer whose work has appeared in the Brooklyn Rail, Words without Borders, and Publishers Weekly, amongst others, as well as in journals and anthologies in the US and abroad. She holds an MFA in Fiction from Columbia University and is finishing her first novel. She can be found at ariellcacciola.com and on Twitter at @ariellcacciola.