Margaret Adams

The risk analysis expert focused on the crack in the ceiling of their one-bedroom apartment as she talked. This was how she always started these conversations: arms folded behind her head, looking straight up.

“It’s like the FEMA guidelines,” she said. “You don’t want to have to communicate all of your emergency response plans when a disaster hits. You need to have gone over everything long before then. Have your plans in order. It’s not pessimism. It’s just preparedness.”

“Such sweet pillow talk,” he said, and rolled over, his back to her.

They’d met at the first emergency she’d worked after joining FEMA. He’d been one of the lead firefighters; she’d been Incident Command. She liked his unflappable air, his leadership style, the way he cocked his head slightly to the right when he listened. She’d tracked him down a week afterwards with an excuse about a debrief that he’d correctly interpreted as an invitation to ask her out for a drink. The drink turned into six months of dating, then two years. Now he kept talking about getting married, opening a joint bank account. It wasn’t that she didn’t believe they would stay together. She just wanted to be prepared.

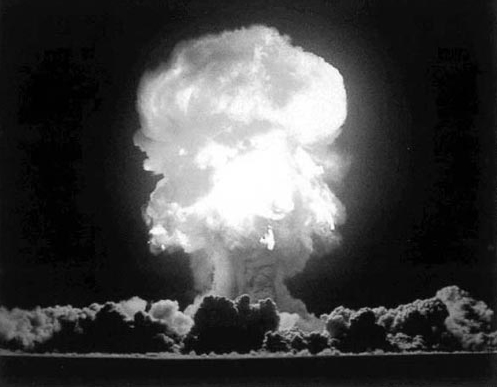

Her mother hadn’t been prepared. When the risk analysis expert had seen pictures of Chernobyl for the first time, she’d thought of her mother: a contaminated ruin growing destructive mushrooms in the darkest recesses of her psyche. Someone whose table, if you ate at it for too long, would render you unfit for human consumption for the rest of most lifetimes. Her sister hadn’t been prepared, either, and there she was, the tornado alley of women, one of those people who got hit over and over again, and now she was raising four kids alone in an East Corinth walkup.

At work, the risk analysis expert’s team moved laser pointers across maps of such hazard-prone areas, tracing schematics of the orange- and red-highlighted corridors so readily decimated by spirals of wind.

“We need to talk about mitigation,” they said. The primary question they kept asking was, how do we help people survive? A possible (but not necessary) follow-up question was how do we help people recover? The true difference between “survival” and “recovery” was something for the qualitative researchers to hash out if there was extra funding.

It wasn’t that the risk analysis expert believed that she could prevent bad things from happening; she wasn’t that naïve. Just that she could prepare for every possibility. A disaster is only a disaster, after all, if the demands of the crisis exceed the available resources. Technically, you can have a multiple casualty incident that is not a disaster. She should know: she had written the manual, defined the terms.

As the risk analysis expert rose in the department, she discovered that there were more than two hundred aging nuclear power plants around the country. Most people didn’t know they were living anywhere near them—concerned that they would be terrorist targets, the government kept their locations hush-hush. The maps were kept in the locked drawers of the upper offices. How do you prepare for what you don’t know about? This was the kind of fear that woke her in the early mornings, cold and gasping.

The more isolated the town, the easier it is to draw up an All Hazards Plan. She knew this. But she had decided to move in with him anyway. If she were being honest with herself, this would be filed in her own personal vulnerability assessment.

“At what point,” he asked her, in the carefully modulated voice that meant he was most upset, “does preparing for the worst become expecting the worst, and expecting the worst become a self-fulfilling prophecy?”

She had no reply.

Like most firefighters, he believed in his own gut, in updrafts of confidence and assurance. “You make your own luck,” was something he told his crews. Intellectually, she understood this. She had studied the standard disaster responses of a populace: denial, deliberation, and then decisive movement. The average person sought reassurance from two other people before agreeing to evacuate. She couldn’t think that way. She focused on functional planning, made core plans that could be mutable enough for every occasion.

In the end, it all went wrong anyway. The disaster hit the week that he discovered the cardboard box in the closet with plans B–Z, the applications to jobs elsewhere, the lease for a studio apartment in another neighborhood, the emails to back-up lovers. And this became the first disaster that she recognized as her own.

Margaret Adams is a writer whose stories and essays have appeared or are forthcoming in Joyland Magazine, The Pinch Journal, The Baltimore Review, and The Bellingham Review, among other publications. She lives in Seattle, Washington, with a husband and housemates who frequently endure her defense of the rationality of owning more than five coffee makers. Her website is www.margaret-adams.com. Follow her on Twitter at @megbeingthere.