Kim Magowan

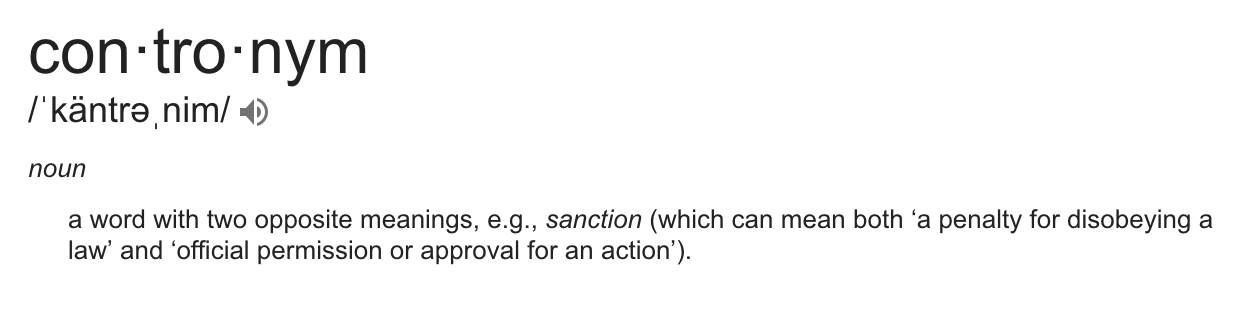

My husband’s colleague at the university, a languid guy named Bill, teaches me a new word: contronym. It’s a word that means both itself and its opposite. “Give me an example,” I say, and Bill says “Cleave. Splice.” If one can fall in love with a word, I do. Bill tells me about the Greek word pharmakon, the root of pharmaceutical. “It means both cure and poison,” he says. “Like chemotherapy.”

My mother is an embodied contronym. She would kiss the top of my head, that spot that’s soft on infants, where the plates of bone eventually fuse, and say, “You are my shiny star.” Then she’d say, “If you keep hanging out with those derelicts, you will never amount to anything.” Later, contrite, she’d kiss that same once-tender spot and say, “You’re my best thing. I made you, and I made you perfect.” I’d think, thing. I’d think, amount.

When people ask me why I don’t want kids, I want to display my mother. I picture her standing on a platform at an art gallery, with a bronze plaque on the base that says Exhibit A.

My husband Nathaniel is a poet and has excellent, expensive taste. Nathaniel loves foie gras, he loves oysters, he orders pricy after-dinner drinks like Calvados. Unless we are out with another couple, in which case Nathaniel will sometimes pull out his credit card, I pay for everything. I am a lawyer and he is a professor, so at one time this arrangement seemed fair.

Nathaniel talks about a vacation he wants us to take, scuba diving to look at whales, and I think about how many days of vacation I get, compared to his stretchy summers. I wonder how much looking at those whales, gray as parachutes, will cost.

California is a community property state, I think, as I watch Nathaniel drink his ruby port. Do I have the power because I pay the bills? Or does he have the power because I pay the bills?

My uncle Murray is a lawyer in Los Angeles, and he tries to convince me to move there. It’s a culture of pure excess, he says. He tells me about two of his clients, a celebrity couple, so famous that even I know their names. Both movie stars, the woman slightly more famous than the man. In their prenup, Murray tells me, was an infidelity clause. If one cheated on the other, the cheater would have to pay the injured party one million dollars. Murray laughs, and says, “People.”

But I wonder about that round amount. Is it so much, when that female movie star makes fifteen million a picture?

In a college Economics class we learned about a study where a pre-school charged parents who were late to pick up their kids. If they were more than ten minutes late, the school instituted a policy to charge them five dollars. The interesting thing is that incidents of parents being late increased after this policy was introduced. Fined, they no longer felt guilty about being late. They paid their five dollars, and they stopped apologizing. “Five dollars wasn’t a high enough cost,” our professor concluded. “Guilt was a better disincentive.”

Our homework was to calculate a cost where the price of being late was higher than the guilt. Twenty dollars was what most of my classmates figured.

At a cocktail party full of dull academics, I find myself in a corner talking to Bill. Or as I think of him now, Contronym Bill, like a vocabulary version of a Wild West outlaw. Earlier in the night, when the hostess, a blade-thin philosopher with sharp little teeth, asked what Deadly Sin we each represented, he said “Lust,” and looked at me with hooded eyes.

Nathaniel said “Pride,” and I thought, Bullshit. It’s a toss-up for him between Avarice and Sloth, but Pride? No way.

Later that night I’ve had too much to drink. Contronym Bill leans into me. Where is Nathaniel? I assume hovering over the philosopher’s bowl of caviar. (She’s married to a venture capitalist. So many of these academics need spouses with real jobs to support them. They’re like sleek, pedigreed cats who shiver outdoors). Bill says something snide about poets that I don’t quite catch. His skin is bad—rough and pitted—but his eyes are beautiful in the way black water in the moonlight is beautiful. I lean towards him. I wonder how much I would pay Nathaniel to get to fuck him. Would ten thousand dollars be enough? Would it be a disincentive? I’m no movie star.

“What are you thinking about?” murmurs Bill.

“Costs,” I say.

Kim Magowan lives in San Francisco and teaches in the Department of Literatures and Languages at Mills College. Her short story collection, Undoing, won the 2017 Moon City Press Fiction Award and was published in March 2018. Her novel The Light Source is forthcoming from 7.13 Books in 2019. Her fiction has been published in Atticus Review, Bird’s Thumb, Cleaver, The Gettysburg Review, Hobart, New World Writing, Sixfold, and many other journals. She is Fiction Editor of Pithead Chapel. Find her on the web at www.kimmagowan.com and on Twitter at @kimmagowan.