Connor Goodwin

It was the last day of the decade and, for insurance purposes, Mama had to pass her stone. This was not her first stone. Like Sisyphus, she’d been up the hill and back more times than you or I care to count.

It happened like this. Mama was dozing in her recliner when she snorted awake. “My back,” she complained. I looked at my brother. He smiled. He knew I hated when Mama whined—her labored breath, the scrape of pain shoveling up her throat.

I returned to my reading: essays on erosional landscapes in Southern Utah. The essays were, at times, too Earthy in spirit, too precious in word, though I agreed with the author’s politics.

“I might have a stone,” Mama said. Where do stones even come from? Dehydration. This far Inland, we mined for water. The Ogallala aquifer, look it up.

Brother and I speculated what the stone might be. Obsidian, he said. Pumice, I said. We were prejudiced toward volcanoes. You see, we both knew the new decade would bring us away from our prairie home so far Inland. I hoped for an island of mud. He hoped for a canyon of wind. I raised my shovel, “Pumice.” He smashed his bottle, “Obsidian.”

* * *

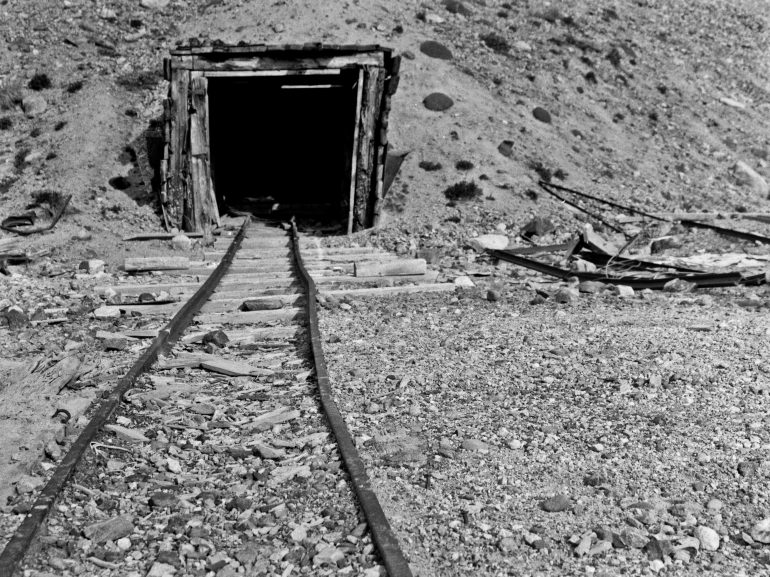

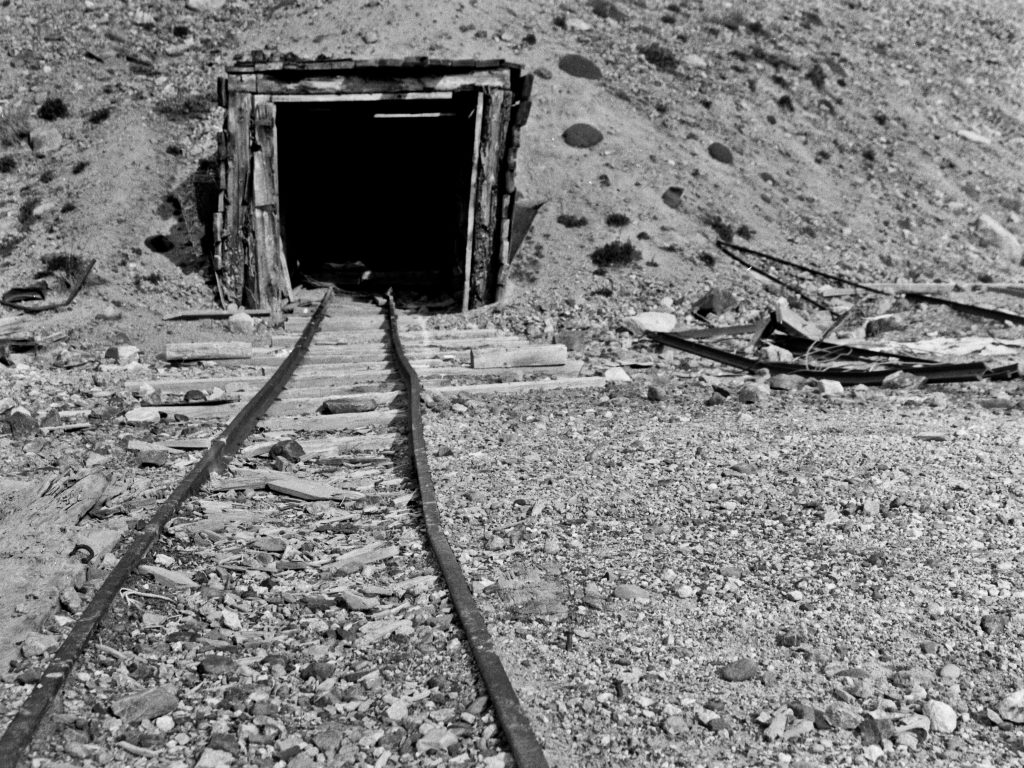

I drove Mama to the mine. The radio was off. The windows were up. It was winter and we saw the last light of the decade. It was every color I ever knew. The color of opal. I’d take a sunset here over anywhere: all the pollution makes the sky burn so pretty. Like a gas-slick puddle.

We entered the shaft and boarded a rail cart and see-sawed into the mine. A thousand feet deep, a dozen parties waited. Mouths masked in cotton to filter dust and disease and desire.

We waited for an opening. A balloon of a woman next to me, a death rattle in her lungs, croaked to her mama, “We’ve been here three years.”

Thankfully, time behaved differently down here. It trickled, pooled, flowed. It was a gamble and we had no choice.

“Feel this,” said Mama and leaned forward. I rubbed the largesse of her back until I felt it. A calcified knot, worried to the surface by sugar, poor finances, and tears. Tears, I learned from my reading, are chemically distinct depending on the emotion they emit.

A room surfaced, meaning a body had been buried. A canary called our name. We boarded the rail cart and I squeak-sawed us deeper into darkness.

The miner put the wishbone in his ears and rubbed the stethoscope over the knot in Mama’s back. “This isn’t a stone,” he said and raised it to his headlamp. “This is a gem.”

That’s when I realized we got it all wrong. There was no mine, no stone. There was only a lighthouse, half-buried, beckoning a great white moth.

Connor Goodwin is a writer and critic from Lincoln, Nebraska. His writing has appeared in The Atlantic, the Washington Post, BOMB, Hobart, X-R-A-Y, and elsewhere. Follow him on Twitter at @condorgoodwing.