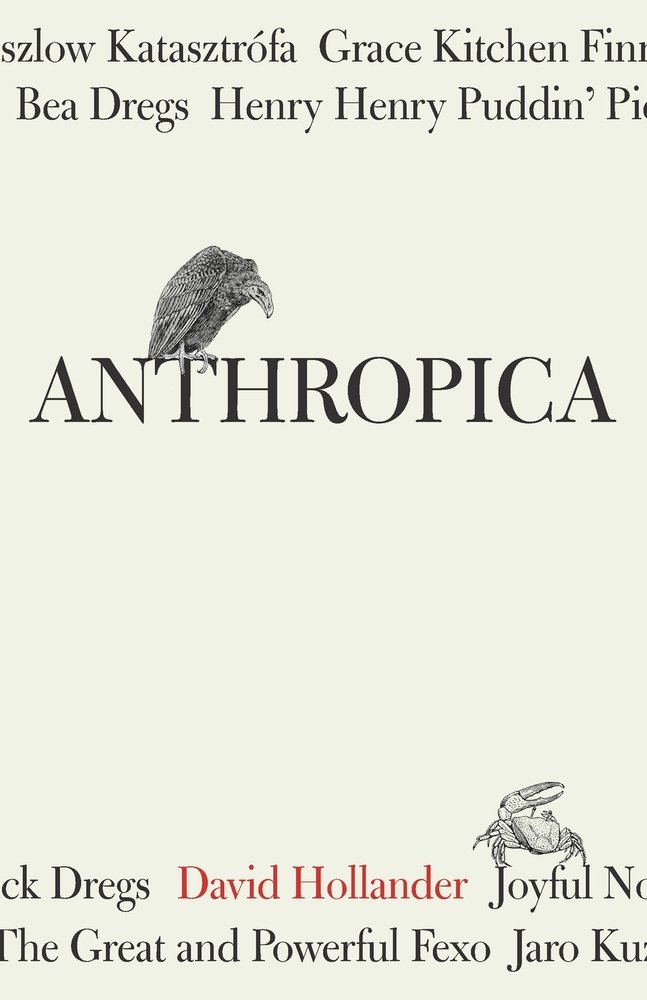

Welcome to another installment of If My Book, the Monkeybicycle feature in which authors shed light on their recently released books by comparing them to weird things. This week David Hollander writes about Anthropica, his new novel published by Animal Riot Press.

If Anthropica were a small and ramshackle village languishing in the shadow of a jagged and ice-slick mountain that had never once been summited, neither by the villagers whose families had lived in the cold damp creases of this Godforsaken valley for generations nor by the heroes and villains populating the stories those same villagers passed down to their children and grandchildren, or better still if Anthropica were merely one of the many creaking tin-walled domiciles that formed this grim municipality, one whose position within the layout of the village—wedged right up against the unforgiving mountain-face and beneath a sawtooth overhang of black onyx—suggested that its occupants were marginalized even within this dour parish that had been forgotten by the world (if it had ever been known to it), or better still if Anthropica were one small boy—a child of perhaps 10 who had been born without a larynx, unable to do so much as whimper—crouched within this domicile surrounded by the feverish bodies of his kin who lay contorted across a stone floor made only slightly less unwelcoming to human bodies by the scattered and half-cured skins of the hyena-like beasts from whom the villagers derived meat and clothing, these family members slowly succumbing to a virus that swept through these unhappy latitudes each so-called spring when the melt-off ran down the mountainside in icy floods of pain, or better still if Anthropica were the liquid black pupil trembling in the eye of that boy-child as he stared vacuously into the cracks and deviations of the withered tin walls straining against the indifferent pull of gravity, then that pupil would right now be dilating, filled with a variety of fear yet unknown to the boy in the domicile in the village in the shadow of the mountain, because that boy knows that you are watching him.

If Anthropica were a set of dishes, no one would believe that you had acquired it as a set, for it would include dishes of every size and every color, dishes that had been forged in Egyptian fires thousands of years before Christ walked the earth, dishes that had been pulled from steamer trunks excavated from the wrecks of a great passenger liner whose mammoth hull had lay beneath three miles of crushing darkness before being discovered by the ingenuity of fame-hungry men, dishes that were in fact not intended to serve as dishes but as sundials, smoke alarms, Frisbees, cymbals, dishes upon which digital information had been etched by micro-lasers in the clandestine hangars of a South Korean intelligence agency, dishes that looked eerily like the petrified or fossilized or desiccated eyes of giant squid, dishes made of gossamer and dishes made of lead and dishes upon whose rims were etched the 9 million names of God, in fact it wouldn’t even make sense to try to explain that this was a set of dishes, that you had just purchased it at your local Pottery Barn, that in fact others just like it were on sale right now, their prices reduced in accordance with the simplest of economic principles (supply and demand), and so you would be the only one to possess a set such as this, and you would never use or display your dishes because you would know that the joy they brought was in large part a function of their secrecy, and so you would tuck them deep into your pantry, back in that same crawlspace where you keep your high school plaques and trophies, and there the dishes would stay until an emaciated and unclothed boy without a larynx arrived at your door one day beseeching you with the deep pools of his dilated pupils for a morsel of food, and you realized that there was only one proper way to serve it.

If Anthropica were a spider it would be a spider that was the last of its kind but that had mated with the second-to-last of its kind (before devouring this hapless fornicator) and thus now carried on its back an egg-sac filled with hundreds if not thousands of tiny replicas of itself, each one no larger than a spore of dust but genetically destined to develop the mature spider’s unusually large thorax, its bright blue coloration, the black diamond-shaped ornament seemingly affixed to its underside, a spider that knew, somewhere in the tiny folds and recesses of its tiny spider brain, that it was the last of its kind and that it must survive long enough to defy extinction, a spider resting in total stillness with the egg-sac on its back like a warrior’s shield, sequestered deep within the musty recesses of a human dwelling built over a century ago (around the time of a great and bloody human civil war), a spider that does not attempt to emerge from its dark and damp haven, that does not attempt to spin a web or to capture prey for it sustains itself on the air alone, its heart the size of a poppy seed and humming in its thorax, the delicate cilia-like hairs of its eight legs aware of the slightest perturbance in the sacred atmosphere of its birthing place, and on the day when the egg-sac has finally ripened, the day when all of those tiny spore-like offspring are due to emerge and race unfettered for their own corners of the ancient human domicile, on that very day a speechless boy with dilated pupils would arrive unclothed at the human entrance to the home that contains—deeper within itself—the spider’s safe house, the mute boy urged inside by a voice the spider would recognize in the same way it recognized a certain pattern in the breeze or a change in barometric pressure, and then a human would open the pantry door, shuffle around some old boxes and cans containing human edibles, reach for the latched cubby at the back wall of the pantry, unlatch and open it, reach its long hairy arms into this dark and damp space seeking out the set of dishes that it had stashed back there, not knowing that the bright blue spider was clinging to the stiff cardboard box, desperation beating through its brain, its fangs bared, strengthened by the weight of forever and prepared to administer its deadly toxin, knowing that everything was happening exactly as it was always going to happen.

David Hollander is the author of the novel L.I.E., a Young Lions Fiction Award Nominee. His work has appeared in McSweeney’s, Conjunctions, Fence, Agni, Unsaid, The New York Times Magazine, and Best American Fantasy, among other reputable and disreputable publications. He lives in the Hudson Valley with his wife and two children and teaches writing at Sarah Lawrence College. Find out more about David at www.longlivetheauthor.com.