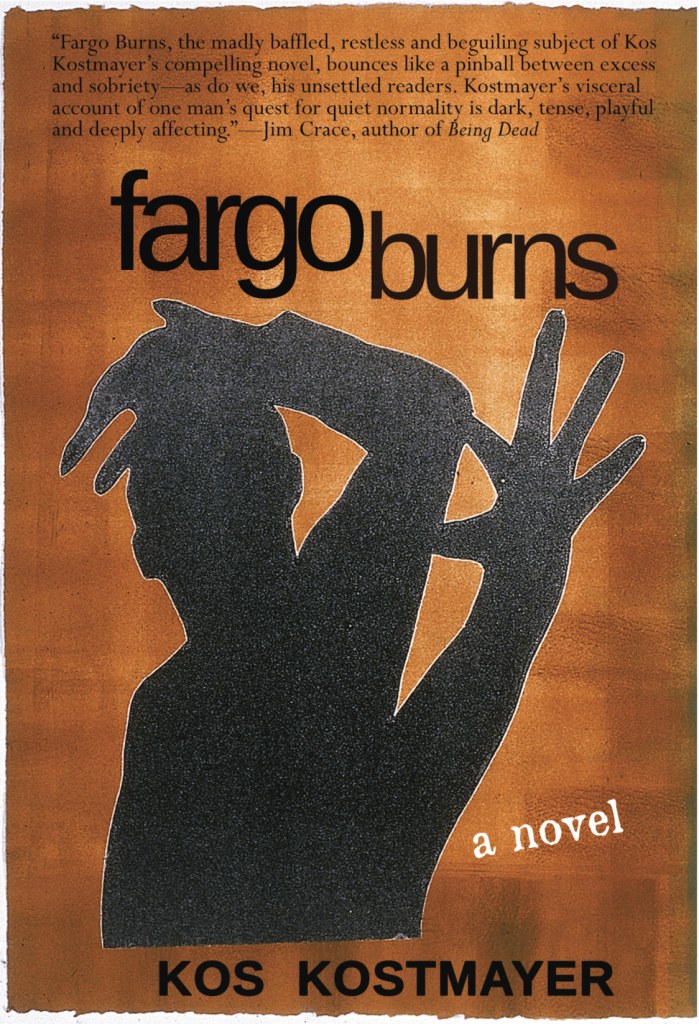

Welcome to another installment of If My Book, the Monkeybicycle feature in which authors shed light on their recently released books by comparing them to weird things. This week Kos Kostmayer writes about Fargo Burns, his new novel out from Dr. Cicero Books.

If Fargo Burns were a nuclear weapon, it might wake up the neighborhood, or rearrange the daily news, or take you out for a snack and bring you back on a gurney.

It might change the weather over Berlin, or turn the Yellow River red, or fling Seattle into the sea, or drop Beijing off in the middle of Moscow, or drift on winds of burning ash and fill the air with missing limbs.

If Fargo Burns were a nuclear weapon, it wouldn’t be a novel or a volume of short stories or a poem or even a sentence. It would be a single lethal exclamation point followed by a long white silence.

Its favorite song would be Time Out For Tears.

If Fargo Burns were a nuclear weapon, it wouldn’t set the city free, or liberate the human spirit in the face of thuggery and lies, or save the whales, or succor the weary in their hour of need. It wouldn’t help you understand your illusions, or show you how to fly, or make you less stupid, or walk beside you hand in hand through every kind of grief and loss. It wouldn’t teach you how to reach the tender spot where loveliness abounds and lovers never die unless they need to say farewell. It would not invite you to discuss the nature of fate. It would not pray for you on rainy days, or lend you its library card, or tip its hat politely as you went by, or tap you lightly on the shoulder and ask you for the next dance.

It would not sound like Billie Holiday. It would not remind you of English tea or make you think of toast and jam. It would not bring to mind the body and the blood that live inside the wafer and the wine. It might sound like an elevator shaft at midnight or like a distant car alarm or like the parent searching at daybreak for the missing child or like the telephone that rings in the rented room where a man in a black suit sits in a white chair polishing his shoes to a fine gleam before loading his gun and going out to greet the night.

If Fargo Burns were a nuclear weapon, it wouldn’t shake you awake at three o’clock in the morning to talk about the author’s insecurities. It wouldn’t bother to blog. It wouldn’t wave the flag, or tickle your fancy, or train your tulips to march for freedom. It wouldn’t bother to praise James Baldwin or mourn the early death of Keats. It would not vote for Noam Chomsky.

It would never (ever!) make you laugh unless it was your last.

If Fargo Burns were a nuclear weapon, it wouldn’t expand your mind or give you reasons to change it. It wouldn’t resemble a tree. It wouldn’t be William Blake. It wouldn’t excite your imagination or celebrate the life of Toni Morrison.

It would eliminate boredom, I guess, along with North South East and West, not to mention all the trees and all the birds and all the roads that lead from here to Mandalay. It would not advise you to drink less or kiss more or be nice or rise up or keep still or write your will or nominate your favorite zinnias to sit on the Supreme Court. It might glow, but so what? It would also burn.

If Fargo Burns were a nuclear weapon, it would not be legible. It might be called Big Boy, but it wouldn’t be funny or shy or kind. It wouldn’t be gentle either. It wouldn’t write a preface on how we met. It wouldn’t suffer from ambivalence. It would get straight to the point and do away forever with rhyme and reason. It wouldn’t hesitate. It wouldn’t argue or complain. It wouldn’t be subtle, uncertain or slow. It wouldn’t wait for money. It wouldn’t wait for love. It wouldn’t give me a chance to call you one last time and say farewell before we go.

Kos Kostmayer is a novelist, poet, playwright, and screenwriter. His work has been honored with the Los Angeles Drama Critics Circle Award for Best Play. Kos served for many years as Supervising Writer and Field Producer for the Emmy Award winning television show Big Blue Marble. Kos is married to the artist Martha Ferris, and he and his wife divide their time between their family farm in Mississippi and their home in the Hudson River valley.