Sabrina Hicks

Lucy sits in her backyard with a ring of dirt around her, cup of water, red paint rocks by her cross-legged feet as she drags her fingers across her cheeks. Two stripes under each eye like a warrior.

“What are you doing, Loser?” her brother says, kicking a stone in her direction, hitting her knee. He’s on his way to his friend’s house and she breathes a sigh of relief.

“Going home,” Lucy says. “To the red planet. I’m a Martian. I don’t belong here.” But she says it quiet, in her own language to keep her safe. If he understood, he’d erupt like the volcanos back home, liquid orange, drying into burnt copper. She looks up at the marble sky, threads of clouds snagging, knows there will be rain.

“I need more aluminum foil,” Lucy says to her mom, but her mom is sitting at a table with so much paperwork around her that her worn expression feels like a black hole, one Lucy is scared of getting sucked into. She starts to feel the gravitation pull, the inevitable crush, and backs away, walking the way astronauts do, so little gravity keeping her down. She walks that way at school, placing one foot in front of the other like Neil and Buzz, only lighter because she’s a girl, she doesn’t leave footprints, she knows how to be a shadow. She doesn’t make a sound at night when she creeps outside to see the moon, to watch it rest on the branches where she slingshots stars across the galaxy. She sings campfire songs to Venus, the one about the big rock candy mountains, where there’s lemonade springs, lakes of stew, her stomach is never empty, and she doesn’t have to change her socks.

The foil in the drawer is from the Dollar Store, the cheap off-brand one that balls into nothing. She hoards pebbles of tin along with the red rocks—a reminder of her return. The foil has good conductivity, it’s malleable, it can bend into antennas, it doesn’t look of this world. On some days, she even thinks it’s enough to get her back to the red planet. She dreams about the rover collecting samples, about how Olympus Mons is the largest volcano in our solar system, over two and a half times the height of Mount Everest and nearly as wide as Arizona. She dreams about that view on Mars, her lungs taking in the thin air, jumping three times higher, how there are lakes of red bean stew in the cavities of that candy mountain—no hunger, sweets every day.

When Lucy signs up for the fourth-grade science fair, she tells the teacher the rover on Mars doesn’t know where to get the best samples. That she can give the scientists everything they need to study her planet. They’re looking for life in all the wrong places. They have to dig below the surface. The teacher musses up her stringy, sun-soaked hair, releasing its earthy smell, and Lucy knows the teacher doesn’t understand. She holds the stink of a dying star.

“Hey, Loser,” her brother says in between bites of his Swanson dinner he threw in the oven for both of them. Her mother is away again and won’t be home for days. There’s a few cans of vegetables in the pantry, bread and beer in the refrigerator. “There is no life on Mars for a reason. You’d fry up with radiation. You remember Arnold Schwarzenegger’s face melting in Total Recall?” He stretches the skin by his ears until his eyes bulge and his teeth chatter like a skeleton, bits of gravy spilling from his mouth.

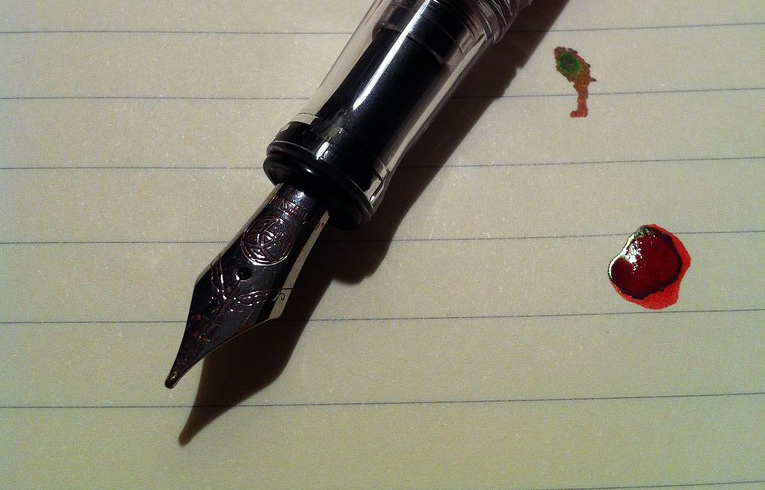

On the day of the science fair, Lucy stands by her project covered in red dust, her rover made of aluminum foil, waiting to explain how it works, wanting to tell anyone who will listen that she should be on a mission to Mars. Earthlings can’t handle that kind of solitude but she can. She was born into a great silence. She knows the language of wind and soil, how something molten can harden into rock. She waits for the judges to make their way to her, after they’re done hovering around projects constructed with Styrofoam balls, painted into perfect miniature planets, projects that help them understand all the ways they have failed as a species, polluting air and waterways, altering temperatures. Projects that, after given their good marks, will end up in a landfill awaiting their thousand-year decomposition. She overhears an explanation of charts and graphs as she waits her turn, resisting the gravity trying to hold her back, humming to her big rock candy mountain, two stripes under each eye like a warrior.

Sabrina Hicks’ work is forthcoming or has appeared in Best Small Fictions 2021, Wigleaf Top 50, Brevity, Split Lip, Fractured Lit, Milk Candy Review, and many other publications. More of her work can be found at sabrinahicks.com and you can follow her on Twitter at @desertdwellera3.