Leah Jane Esau

When I was a kid, we had bad teachers. The teachers ate lunch in the staff room and left us in our classrooms, unsupervised. One year there was an incident: some boys started a food fight, culminating in someone throwing a textbook, which was heavier than they anticipated, and they’d hit the wrong target—a girl, with angel blond hair and small ears. After that, the school recognized that we needed supervision, but they were unwilling to pay, so they implemented a program where a student in the Sixth Grade would eat lunch in each classroom. These Grade Six “lunch supervisors” were paid in a point system: each point was a raffle ticket, and at the end of the year there would be a draw.

“Only one winner?” the kids said.

“Doesn’t sound fair.”

“That’s a lot of work for all of us, but only one gets rewarded.”

“And what is the prize? Give us an example.”

These were smart kids. They knew nothing came for free. They understood how capitalism worked: they should be paid for babysitting. In the end, they negotiated: a draw once a week, or less homework, or an extra field trip: I forget the details. But I do remember our lunch supervisor: Dee.

Dee was in the Sixth Grade, but she’d been held back a year. Her full name was Amanda, but she was mentally handicapped and couldn’t say her name, so someone had renamed her. She had great difficulty speaking—beyond a simple speech impediment: her thoughts needed more time to come out; her mouth was slow to form words. I’m not sure why the teachers assigned her to our class: we were notoriously the worst.

One day, we were being particularly rowdy, and Dee asked us to be quiet. We ignored her. She waddled down the rows of desks. She moved like a penguin, shifting her weight from one side to the other. That was how she walked. She tapped us on the arm and asked us to be quiet please.

“Be quiet pwease,” the boys echoed.

“Too wowdy. We’ll get in twouble.”

Then another Grade Sixer came in, from the classroom across the hall. Her name was Maria, and she was so pale you could see her veins.

“Can’t you do anything right?” she asked Dee. She slammed her fist on the desk and screamed, “SHUT UP AND PUT YOUR HEADS ON THE DESK!”

We did so immediately, surprised, shocked. No one had ever yelled at us with such ferocity.

“See?” Maria said proudly. “That’s how you do it.”

She swiveled around and left.

Barely a minute passed before our teacher arrived, furious to be interrupted. She yanked Dee’s ear.

“Don’t yell like that!”

Dee tried to speak. We could see her lips trying to work.

“I didn’t,” she said after an excruciating pause.

“I heard you.”

“It … wasn’t… me.”

“It came from this classroom. I heard you.”

It was painful watching Dee try to talk. I don’t know what came over us, why we sat there, why we didn’t speak up. We were too startled, too scared. It would’ve been so simple to explain that Maria had left her classroom across the hall and had visited ours. Dee tried to explain, she gestured to the door. But she was slow. Her words needed time. In the end, she could only repeat, “It wasn’t me.”

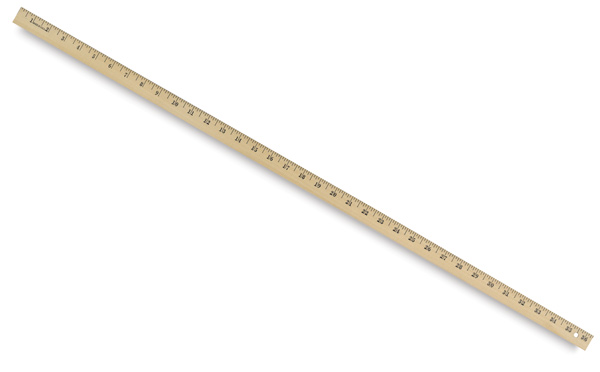

Infuriated by this “lie,” our teacher took the meter stick that rested on the lip of the chalkboard and whacked it down on Dee’s bare arm, where the sleeve of her t-shirt ended. I’ll never forget the sound, the slice of the air, a swoop and then the whack, as it hit her skin. This was back in the 70s when corporal punishment was legal, but there was a fine line between what was decent and what wasn’t.

Then our teacher replaced the stick, and left, and we sat in open-mouthed silence.

Dee was on the floor, trembling, her hands over her head. We lifted her up and sat her in the chair. The meanest boy went downstairs to the freezer and fetched an ice pack reserved for sprained ankles. He put the ice pack against Dee’s arm, where there was a red welt, a streak, a line.

Years later I saw her again, at the grocery store. She had the same haircut, straight brown bangs and a ponytail, and she looked the same, just a little taller. She was shelving pasta, and I wondered if I should introduce myself, if she would recognize me. I decided I should say hello.

“I went to school with you.” I named the school. “But I was a few years younger.”

I asked her about her life. She lived with her mother in the same house she’d grown up in, and she’d worked at the grocery store for ten years. She and some friends had taken a road trip last winter, to Florida, where she’d swum in the ocean. I was thinking of our childhood, and I wanted to say, “Do you ever think about that time?” but the truth was that she looked happy. Why bring up the past?

After we talked, she hugged me, and I saw it there, on her arm, poking out from the short sleeve of her uniform: a thin, white scar, barely noticeable unless you were looking for it.

Leah Jane Esau’s fiction has appeared in PANK, The New Quarterly, Bodega Magazine, Grain, The Dalhousie Review, and others. In 2014 she was nominated for the Bronwen Wallace Award, with the Writer’s Trust of Canada. Follow her on Twitter at @LeahJaneEsau.