Reviewed by Josh Kleinberg

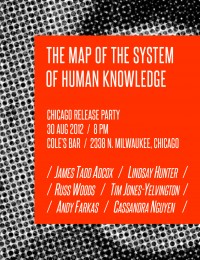

The Map of the System of Human Knowledge, James Tadd Adcox

Tiny Hardcore Press

ISBN-13: 9780983562559

$12.00, 138pp.

James Tadd Adcox’s debut collection, The Map of the System of Human Knowledge is a structured series of encyclopedic entries, its table of contents a squid of carated subdivisions. Atop each of the four content page headings is a constant reminder that the forthcoming sections fall under a weighty umbrella: UNDERSTANDING.

Understanding, of course, is and will necessarily always be incomplete. And so it makes sense that this be a tiny book, written in shards (The history of animals, to give an example, can not be mapped. But once we’ve made this admission, we can ask for a demonstrative story about the mice that were or were not ever in your walls).

The entries are further split into three sections: MEMORY (bracketed at the side as HISTORY), REASON (PHILOSOPHY), and IMAGINATION (POETRY). There’s a sort of tangential way in which the best flash collections function as exploded novels or dissertations, their shards scraping and embedding themselves in you, until you take one to a lonely lunch and shed a tear onto your neon-relished Polish, and you’re not sure you can really point to all the connective tendrils constricting so tightly around your tiny heart, but you’re sure that something bigger is happening. There’s a definite temporal arc at work in the sectioning: Memory representing the past. Reason our dealings with the present. Imagination our attempt at constructing our future. But this most obvious organizing principle, chronology, is continuously subverted by the imposition of each category onto each other: The collection begins and ends with entries titled “Sacred,” portions of philosophy are devoted to the “Art of Remembering,” HISTORY has one section entitled “Literary History,” another called “Memoir,” and the book’s final image, under the category of “Sacred Poetry,” is a memory. Adcox writes in sacred geometry, the sections a sort of shape-shifting currency in which he adds and adds and divides and deciphers formulae in form and in non-form.

We see, in Adcox’s images most deftly, shades of the classical storytellers—Marquez in the gossamer wings of Iranian homosexuals—but actually it becomes clear that Borges is probably the more apt Latin fantasist comparison. The world of Map has its own separate mythology, -as in Borges’s best, and Adcox is building an entirely new ecosystem, his rules clarifying themselves, as in our own world, empirically. But the rules, and here is something we either want to or must (depending on who you ask) believe of our own universe, are not fixed—sometimes devolving into irrational calamity, where the geese become the kings, nails unplug themselves from the walls, characters’ pants balloon and contract—the system itself a pulsating thing.

As well, there are Kafka’s desperate dealings with bureacracy, Calvino’s false starts in “Narrative,” Tolstoy’s asceticism in “Natural Theology,” but these stories are concerned less with copying and more with contemplating the preoccupations of its forebears. This is a universe whose most humane knowledge we recognize—the arm-twisting expression of love when a father begins to fear the abuse of his daughter, teenagers still nervously groping at each other. In Adcox’s, as well as our world, we still don’t fully know what we are, and we all harbor a similar suspicious notion. As he writes it: “[h]ow wonderful we once must have been.”

The HISTORY section is the largest and most full of the three. I’ve seen Adcox read all frantic and strained from his novel-in-progress, but the vignettes of HISTORY are not those. The characters here are the quiet, glazed-eyed malcontents of Carver, constantly asking for miracles. Nearly every one of these stories is about someone being technically wrong in the strictly rational sense, with such a pure heart that we do not pity or patronize them—because it is not naivety, but something better. No, we don’t pity them. We envy them.

In “Working and Uses of Skin,” we recognize the religious urge toward an authority figure. Robert Bly’s “naive man” is the one who sees no value in constraints. A major component of Nietzsche’s Superman is the ability to impose them on oneself. The Libertarian believes that we’re supermen. Alcoholics know we’re naïve.

And here’s the thing: all those people who are wrong? They’re not wrong. If you’re a logic (wo)man—a tendency I’m pulling recently out of—there’s a way in which you pine for it. Not because it’s more innocent and you hate being right. Because it taps something true that you’ll wish you could still tap, yourself. The secret we so often keep from ourselves is that the rational is neither the only, nor always the best, navigation system. The daughter knows more about the monsters than we do—and not merely because of a wild imagination. We rip apart vacuums. We show her. And still she knows. The daughter is not wrong. She’s only tuned to a different frequency. “See,” the story ends. “[I]n the dust: something begins to stir.”

As HISTORY moves on, we begin to notice a destruction myth: something nihilistic in the woman who births furniture—a negation of commerce (and sure enough, when times get tough, the soldiers arrive to ruin everyone’s armoire party). Toward the section’s end, the irrational, which in the first stories pops through the narratives in tiny bursts, becomes a vehicle for the more outlandishly avant. These, for me, are the moments where the most beautiful capacity of public remembering—the sculpting of empathy—is perhaps sacrificed a little. But it seems clear that the dissolution of the historical section is intentional: it morphs from the unmiraculous first entry, through a world of tiny miracles and misconceptions, into full-blown chaos. You can palpably envision the dam of Human Knowledge bursting in the background, Wagner blaring, as a shadowy couple argues through their teeth in the glitchy gift shop of the museum of irregularities.

The history section of human knowledge seems to have a death impulse.

While Adcox is at his best, to my mind, when he focuses not on the big chaoses or the wholly grounded, but on the small miracles—the home intruder candidly deciding against a robbery, the tiny 6-year-old born from the loins of some new saint—the PHILOSOPHY section continues into more rhetorical territory. The characters advance theories and, in doing so, show us to an extent where their hearts lie. Readers will hear an inkling of the existential optimism from the I ♥ Huckabees “tiny connections” speech in the “Metaphysics of Bodies…” entry. “It’s weird…” says a gray-visaged lover. “[B]oth of us getting turned on with him trying to figure out where I end.”

We learn, as in “Mechanics,” that some of what we see has unexpected innards, and that some—as in “Statics”—is unexpectedly empty. In “Acoustics” Adcox discusses mysticism, the tenuous arguments we allow ourselves, mindfully, to buy into; the attempts to inject science, and the simple fact that it’s just. not. all. to be found there. The section ends with a lie: “Praise Jesus,” a son hears his father’s mistress say. “Everything’s been put right.”

Where the HISTORY section of human knowledge encompasses our anecdotal dealings with the world, and where PHILOSOPHY is the theorizing, it is POETRY where the two come together, sometimes favoring the former, sometimes the latter, sometimes the two balanced equivalently.

HISTORY is a narrative but it’s a narrative that at the least claims to be motiveless. In POETRY, Adcox brings in the possible vs. the actual, and we begin to see humanity infused with philosophy. And isn’t that what art is? These are the entries where Adcox gives himself space to roam but always returns to the ground at the end. They’re a little weird, a little out there, but they resolve, as in “Music” (both the entry and the entity writ large), there are tiny theses advanced. And though we know we do not have complete conscious access to the what and why of it all, we can be sure that we understand when “[s]ome huge weight crawls from our hearts.”

Joshua Kleinberg is a poet. He is a contributor at Coldfront, representing Ohio, which is where he lives. Links to his work are here: http://joshuakleinberg.com And here is a video of him getting arrested.