Reviewed by Andrew Fry

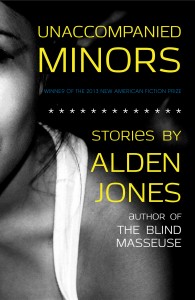

Unaccompanied Minors, Alden Jones

New American Press

ISBN-13: 978-0984943999

$14.95, 168 pages

When we hear the term unaccompanied minors, we imagine young travelers ushered on and off airplanes by nurturing flight attendants, wearing wing pins and given extra snacks during flights so they know they are cared for. In Alden Jones’s collection of short stories, Unaccompanied Minors, the young people we meet are on their own, for better or worse; there is no hand-holding here. The collection is a series of expeditions into places most readers might not dare to venture even as adults. At just one hundred sixty-eight pages, it is possible to read this book in one sitting, which is good, because as each adventure ends, the reader is taunted by the next.

In her first book, The Blind Masseuse: A Traveler’s Memoir from Costa Rica to Cambodia (University of Wisconsin Press), winner of the Independent Publisher Book Award for Travel Essays and recently longlisted for the PEN/Diamonstein/Spielvogel Award, Jones calls on her experiences accumulated while living, working, and traveling in over forty different countries and compiles them into a quasi-guide for the well-meaning traveler. In the seven stories that make up Unaccompanied Minors, winner of the 2013 New American Fiction Prize, Jones wraps the personal experience with people, places, and cultures gained in her travels around a cast of delightful but damaged characters, and then takes us on a fast paced tour along the rough edges of society.

Though the cerebral and culturally sensitive narrator of The Blind Masseuse would object to the increasingly popular phenomenon known as slum tourism, Jones does something like this in her stories. The narratives in Unaccompanied Minors hinge on poverty, drug abuse, physical deformity, abortion, underage sex, and prostitution. These stories echo the theme of young people on the verge of something, in some sort of perilous, dark situation. Combined with Jones’s torrid imagery, the reader is left with the notion that, although these extraordinary stories may be fiction, their subject matter is painfully real.

Jones’s narrators display a degree of guard dropping intimacy that leaves us vulnerable enough to contemplate, or even feel complicit with, their story’s illicit themes. Through variances in point of view, Jones attacks the reader’s defenses from angles we can’t predict. The stories “Something Will Grow” and “Thirty Seconds” are in strict first person singular point of view, while “Shelter” and “Flee” vary back and forth between the first-person singular and plural form. In “Something Will Grow,” Lanie, the story’s narrator, speaks as if she is explaining her difficult situation to a friend, while the young girl who narrates “Thirty Seconds” almost sounds as if she is giving a statement to the authorities. In “Thirty Seconds,” the story of a child who suffers an accident when both his parent and his babysitter are nearby, Jones nails the babysitter’s detached, “it’s not my fault” indifference—desperate to believe that she wasn’t to blame. “Sin Alley,” by far the most provocative story in the collection, is told from third person limited, centered on the story’s protagonist, a young gay man named Oscar who falls in love with a prostitute. However, it is the two stories told in second person point of view, “Freaks” and “Heathens,” which highlight Jones’s range. Although both are technically written from the second person perspective, the styles in these two stories—one a direct address from one character to another, the other a stand-in for first person—are as different as the stories’ themes themselves.

Jones’s love of travel is apparent throughout the collection. From the “stony trails” of Appalachia to the dark alleys of San José, each setting is invigorated with Jones’s keen sense of place, detail and command over language and irony. She takes us from the mind of a straight girl in the first story, as she tries to keep her lesbian friend out of her pants, to the mind of a lesbian in the last story, as she tries to figure out a way into the pants of her straight friend. She leads us blind into the forbidden confines of a teenage girl’s head, drowns a little boy in the country club swimming pool, and then deposits us on the side of a road in rural Costa Rica to watch tractors spilling caña as they lurch through “sugary mud puddles.” Before we know it, we find ourselves in a male brothel, where boys sip from cans of Imperial beer and discuss the few things they won’t do for money. Throughout, we are confronted with so many unpleasant truths imbedded within Jones’s beautiful lies, it is impossible not to wonder how much is fiction, and how much is cleverly disguised nonfiction.

Unaccompanied Minors is an artistic and intrepid exploration of the provocative and the unmentionable. While many of us often choose to turn a blind eye to these difficult realities, each and every one of them deserve our careful consideration, and Alden Jones presents them to us in a thrilling manner that makes us dare not look the other way.

Andrew Fry lives and writes in southern Indiana. His work is forthcoming at NewStoriesfromtheMidwest.com.