M. C. Armstrong

Think lacrosse and plaid, spring break and date rape, trust funds and bong hits. This is Chaz Reems from a distance, and he half knows it. He’s the Democrat’s dream of the Young Republican. He’s white and ripped with a Prince Valiant haircut and he’s covered in high-end brands: Polo and Nike, Abercrombie and J. Crew. He calls Hunter, his best friend, “Bra.” They both belonged to The Bill Cosby Sweater Club at their high school, but after the group was disbanded “in light of recent events,” Chaz and Hunter needed a new excuse not to come home after school on Tuesdays, so one of their mutual friends, Kenyon Rudd, suggested they all infiltrate the Young Republicans.

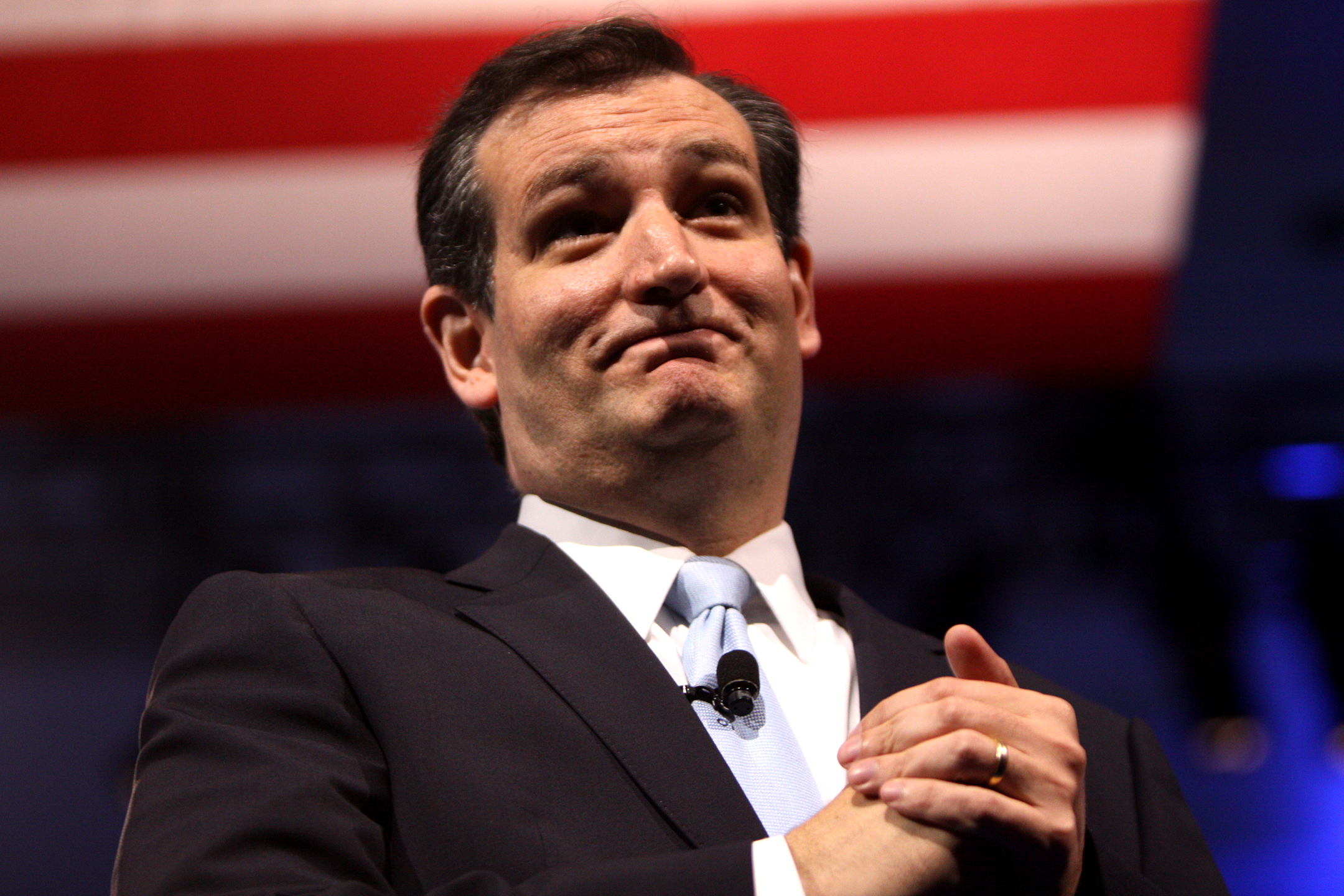

They wore collared shirts to the Tuesday meeting, plaid shorts and extra Axe cologne. They stoked the prankster fires of their imaginations with a few vapes before entering the corkboard framed classroom of the YR adviser, the basketball coach who doubled as the AP Government teacher, Bill Lockhart. The lead item on the agenda was Ted Cruz’s upcoming fundraiser at the Lee-Jackson Hotel.

Lockhart told them to sign their names on the yellow legal pad and grab a seat and a soft drink. He talked about needing “boots on the ground” and “supporting the troops.” Chaz, trying to fit in and make Hunter and Kenyon laugh, drew pictures on scratch paper of Coach Lockhart with a rubber neck performing outlandish calisthenics, his big buck teeth coming perilously close to his groin.

“We totally need to go to this event,” Chaz said.

“I’ll wear a burka,” Hunter said.

“I’m going to go all Beyoncé and wear a Black Panther getup,” Kenyon said. “I’ll oil my biceps,” Chaz said. “Wear that Confederate trucker’s hat and a bunch of flag pins.”

The deal they made was this: Anybody who could score a picture of themselves with Ted Cruz while their balls hung out of their zipper would win five bucks, but you had to Instagram it to collect. They all carpooled and vaped up in Kenyon’s Hyundai Elantra while listening to a band called Comatose Narc. They stared at themselves in the drop-down visor mirrors, Chaz glistening with mineral oil and dressed in pleated khakis, his blue button-down shirt suspendered in well over fifty flag pins, his shoulder length hair tucked behind his ears, the Confederate trucker hat too conservative even for Ted Cruz, Kenyon argued at the last second.

“You’re just saying that because you’re black,” Chaz said.

“I’m saying that because I’m black and I want to see you make a fool of this motherfucker who doesn’t like black people. He’s not an idiot,” Kenyon said. “He might go for the five hundred flag pins, but he ain’t touching a Confederate flag with a fifty-foot pole.”

Chaz stuffed the hat in the glove. They filled the Elantra with a mist of Axe. They cocked their heads back and dropped in the ceremonial Visine. As they walked under wet stars past an empty pool, toward the dull orange glow of the Lee-Jackson, a hotel off the interstate named after Robert E. Lee and Stonewall Jackson, Coach Lockhart suddenly sidled up alongside them and, because Hunter was the eleventh man on the thirteen-man basketball squad, Lockhart called him out by name and placed an arm around him.

“This is a big night,” Lockhart said, dressed in a gray pinstriped suit with a gold and maroon Redskins tie, the clip embossed with an elephant.

They stepped into the elevator in the lobby. The coach had some kind of grease in his hair, like this really was a big night for him, like he really, really liked Ted Cruz, and Chaz, to get a rise out of Kenyon, joined in the embrace without invitation. He put his arm around Coach Lockhart and asked him “When was the exact moment when you knew you were a Cruz man?”

Coach Lockhart greeted the question with a solemn stare that seemed to find pinkness in Chaz’s eyes that the Visine had failed to neutralize. He smelled of talc and Bay Rum, like the headrest of Chaz’s grandfather’s old La-Z-Boy. The four of them waited for the elevator to take them up to the ballroom on the second floor, but the door wouldn’t close and Coach still hadn’t answered the question. Chaz wished he hadn’t said anything. Was he seconds away from a five-day suspension? Was he really this high? Who was fucking with whom here? As the elevator closed, Lockhart turned to Chaz and finally said:

“I wouldn’t call me a Cruz man, son. Not yet. But I believe fortune favors the bold and that business as usual will destroy this country. I think we have lost our compass. I think the Muslims are winning. I think we are getting fat and stupid and I think we need a period of austerity and sacrifice before we can get our bearings back, not more debt and deferral and placation, leading from behind. What kind of world do we leave young men like you if we say there are no consequences for the actions of your fathers? When Cruz led the shutdown of the government, he took us a step closer to that moment of sacrifice that we all know is coming. That was when I started to listen. And that’s what I come here tonight to do: listen.”

Chaz Reems, stoned beyond belief, his arm still locked around Coach Lockhart, didn’t quite know how to respond to this moment of candor, the provisional quality of Coach’s response, the basic humble desire to listen to a man who might be the only man prepared to act on behalf of the nation’s need to do this thing “we all know” we need to do: sacrifice.

Chaz nodded gravely at Lockhart and looked away, found his own oiled reflection in the elevator’s mirrored ceiling. They marched off the elevator and were assigned their various tasks. Chaz would be in charge of bussing the buffet and monitoring, among other items, the Swedish meatballs. He was given a white apron that partially concealed the dense studding of flag pins. He was asked by Marjorie Wimsatt, the maroon-haired chair of the county’s Republican party, if he was feeling okay, if maybe he wasn’t coming down with a fever or something and if he should really be standing over the food.

“You don’t look so good,” she said.

“It’s just a moisturizer,” Chaz said.

Although Marjorie Wimsatt didn’t push the issue, Chaz started to wonder exactly what people were seeing in his eyes, and he started to dread the next lie. Real sweat started to infuse the mineral oil. The room started to fill, Rotarians and Mexicans and men and women, Shriners and Boy Scouts—a large gathering of all kinds of Americans toothpicking the Swedish meatballs Chaz stood behind like the cafeteria ladies he never really thought about except in terms of how dead and fat they looked, he started to wonder if maybe he’d smoked too much pot and if maybe he was getting everything about America wrong, and how all these sincere people would feel if he brandished his balls for nothing more than a photo. He overheard people talking about Trump and the way he’d called Cruz a pussy and how “America needs to grow up.” He heard someone say that Ed Gillespie was on the way and that the Senator was with him, and Chaz felt like that name should mean something: Ed Gillespie. Ed Gillespie. Why doesn’t that name mean anything?

“Dude,” Hunter said to him at one point. “Are you all right?”

“I’m fine. Why?”

“You look like you’re holding in a really big shit. If you have to go I can give you a blow.”

This was one of Lockhart’s choice phrases from basketball that Hunter loved to mock. To give a blow was to give a break, a breath, a little relief after somebody had gone hard for a long time. The joke did what jokes are supposed to do. It woke Chaz up, ripped him out of his guilty reverie, the way Coach Lockhart’s choice of the word “sacrifice” had rattled him back in the elevator. There was something about that word and maybe the other word, too: “listen.” Had Chaz ever really listened to anything?

Chaz marched into the men’s room, thunderstruck by just the word: Men. He sat on the can, his pants around his ankles purely for good measure, because Chaz did not have to poop. He formed a steeple with his fingers, looked down at his growing thatch of pubic hair, a penis that had never seemed smaller, and he imagined his grandmother stapling the penis inside the sac, the scrotum, this weird thing that suddenly felt like a medieval sleeve—a satchel—of hard boiled robin’s eggs, yes, a magic skin baggie for a gnome on a secret mission in a magic forest, and Chaz wondered if he was the only person whose thoughts were continually invaded by gnomes and anxieties about cock size, and it bothered him how easily a penis could shrink, and he wondered if he was just like his penis, so quick to wilt and hide, his fifty flag pins nothing but a shield, his oiled body and his pleated khaki pants nothing but a shield, the prospect of returning to the Swedish meatballs nearly nauseating as his head sank into the demolished church of his hands.

Chaz promised himself that he would never smoke pot again, but no sooner had he made that promise than he heard all the Republican people cheering in the ballroom and he knew it was for Ted Cruz, whom Trump had called a pussy, but who was the real pussy? Chaz had a job to do and the simple fact was: He was afraid to do it. Somehow, the clarity of it just struck him while he was sitting on the shitter listening to all those people clap and scream. It was like the noise just cleared his head and blew out the pipes. The job of the toilet is to flush shit. The job of the sink is to wash hands. The job of the dryer is to dry hands. Chaz’s job was to go “balls out” and get some ultra-sweaty pics with Ted Cruz.

And so Chaz Reems, with a soundtrack of stern and noble horns playing in his gnome-infested brain, recommitted to his Instagram mission, his desire for that five dollar bill and all the followers and chuckles he’d deliver if he could pull this off. He marched back into the Lee-Jackson ballroom. The lights were low. The Senator, with his thick black hair and his wincey face was pacing the stage, his earpiece in and a program or a pamphlet or a set of talking points scrolled in his right hand. This was it. This was the man of sacrifice. This was Ted Cruz from Texas, the face from TV whom Chaz had never really listened to before, and, Jesus, it was the stoned dawning of this awareness and that word again—listen—that kept him from immediately returning to his Swedish meatball station. Instead, Chaz moved as close as he could to the stage. Before he took out his balls he wanted to try to really listen, get a really good look at the senator’s face. He wanted to compare glistens. He wanted to see the brand name on the earpiece. He wanted to look the senator in the eye and see what could be gleaned from a sincere, wordless exchange. He wondered if there might be some sort of tractor beam of connection between the two of them if they just kept from talking, if they just stared at each other. Chaz passed by the inscrutable Visined eyes of Kenyon Rudd, past the dugs of a man with a nametag that said Kilby Dick. He stood between the shoulder-padded shoulders of Marjorie Wimsatt and Coach Lockhart with his Redskins tie, the Coach apparently doing exactly what he claimed he’d come there to do: listen.

Chaz tried to listen. He looked into the viewfinders of all the cell-phones held aloft by the other Young Republicans and what were probably semi-prominent Republican figures from Virginia, West Virginia, and Maryland. He stepped even closer to the stage. Maybe this would help him listen. There was now nobody closer to the senator than Chaz. The camera flashes washed over him with their reminders that this was not just a ballroom of words, but also a gathering of light, an event much more primitive than perhaps any of these people were fully prepared to acknowledge. Only Chaz Reems was truly aware of the primitive essence—the tribal gathering of meat and sweat and light—this night at the Lee-Jackson Hotel.

“Dude,” Hunter said to him, poking him hard on the shoulder. “Get back to your station.”

Just like the words men and listen, this command—get back to your station—rocked Chaz Reems. He did what he was told, and he knew it was against his will, but maybe this is what “sacrifice” is all about. Chaz wanted to get closer to the Senator, but here he was getting ordered around by his own friend to get back to his “station,” as if every force in American life was conspiring to keep him from getting close to The Truth, or maybe it was the other way around, and to Chaz, as he dizzily threaded his way through the Rotarians and Shriners back to the heated silver dish of Swedish meatballs, The Truth became increasingly clear:

“You don’t know anything,” he said to himself.

Ted Cruz was not the pussy. Chaz was the pussy and he felt gutted by this revelation. He waited like a mannequin behind the heated silver dish with its dozens of Swedish meatballs pre toothpicked for the Republicans, the appetizers striking him like a million micro penises, each affixed to a single testicle, all of it a mirror of his cowardice, his inability to stand up for himself and his entire generation that never really listened to anything, never sacrificed anything. As Ted Cruz began to make his way past the cheese wheels and vegetable trays, shaking hands and exchanging pleasantries, his earpiece out of his ear, his cheeks crinkling with life, Chaz’s head was cluttered with a static of voices, his angry libertarian brother, Josh, ranting over the phone about ISIS and his six-figure college loan debts and how the New World Order wanted you in debt so you’d be compelled to work for “The Matrix,” and there was the tired voice of his mother who now refused to watch the news, and his father with his hair implants designing web pages with his twenty-year-old girlfriend in Indonesia, and his aunt and uncle who walked out of any movie about war, and there was his grandfather who kept telling him to “think about learning a skill,” and louder than all these humbling voices Chaz heard were the voices he’d never heard, the fact that he’d never once taken the time to listen to an entire speech of any politician, and even here tonight, with the speaker speaking right in front of him, he’d been so trapped inside his Ritalin-riddled, weed-diffused skull that he hadn’t latched onto a single meaningful phrase, and maybe that was all because it—life, politics—The Truth—wasn’t about words. Maybe the primitive truth he’d felt out on the floor as he’d approached Cruz’s moist, wincey, earpieced face was The Truth he needed to pursue even further. So as the Senator stepped closer and reached into the heated silver dish and retrieved a single Swedish meatball, Chaz figured now was the time to use the real measuring stick and, thereby, honor not his promise to his friends, but to that higher part of himself that might well be the whisper of God.

“Swedish meatballs,” Chaz announced to the Senator and his retinue, immediately feeling foolish for not being able to summon a remark more witty than a mere label for the thing in front of them.

“Meatballs,” the Senator corrected with a wink.

Chaz felt stunned by the revision, the shared moment, the bare but teeming fact of exchange. He felt the warmth and the wit of that correction and he felt the wink flood his body with endorphins, waves of knee-shaking warmth coursing through his Kush-softened soul. The Senator had listened to him and the Senator had responded.

“Sir,” Chaz said.

Behind the Senator stood Kenyon with wide eyes and a cell phone held like a shield. Chaz stepped from behind the buffet table, arms spread wide like Christ, his white apron concealing the absurd arches of flag pins, his Confederate flag hat tucked safely in the glove of the Elantra, his sheen of oil and sweat more the misleading mark of a working class Joe than a stoned prankster to the undiscerning eye of the camera, and he looked into the eyes of the living, breathing Senator and approached his remarkably fit body, the sense of throbbing warmth Chaz had felt from behind the buffet table only intensified, and he didn’t quite know what to make of it, and as he wrapped his arms around the swallowing Senator and clutched his living, throbbing Senatorial flesh and stroked him with fingers that had never felt more like antennae, Chaz felt something grow inside, and he wondered if the Senator felt it, too, and if other men might also feel it if they just had the courage to give a chance to this real American.

M.C. Armstrong’s fiction and nonfiction have been published by Esquire, The Missouri Review, and The Gettysburg Review, among others. The winner of a Pushcart Prize, he embedded with JSOF in Al Anbar Province, Iraq and reported extensively on the Iraq War for The Winchester Star. He is the guitarist and lead vocalist for the band Viva la Muerte. Find out more at mcarmstrong.com or follow him on Twitter @mcarmystrong.