John Englehardt

When Helen stops the car under the sign for American Airlines and doesn’t get out to say goodbye, I consider launching into a tirade in which I list all her faults. Like how she’d be sexier without so many moral hang-ups, how she’s dependent on her officious parents—and so on. In this fantasy I end by saying, “I want to marry you and all your fucking problems. I wish that was enough,” which is admittedly just something I heard in a movie. And then of course she starts to cry, so I slam the door and walk into the airport without looking back.

But that’s not who I am. Instead, I lean in for a kiss, then I get out and shut the door by letting go. After herding through security, I order an artisan pizza in the food pavilion and listen to music. I sit.

At the gate, I flip through an old Skymall to pass the time. Commemorative baseball jewelry. Posture-improving tank tops. A service that will paint a portrait of your cat as royalty in Elizabethan garb—it ships within two days.

Wedged in the magazine I find an insert advertising a housing development called Kentbrook. On the brochure, there’s a panoramic photo of a cul-de-sac nestled on a quiet ridge. Lines of cherry trees. Brick houses with complex gables. The Cascade Mountains jagging across the horizon. On the back, a picture of a chunky husband alongside a wife who embodies modest desirability, right down to the ruler-straight hair and half-exposed collarbone. I find myself envying Kentbrook’s comfort and security more than I disparage its conformity. How could they not be happy? So much for everything I learned in college.

I buy a coffee and throw half of it away before boarding the plane. The in-flight movie is a romantic comedy, which I boycott by not taking complimentary headphones, but then I end up watching it without sound. It starts with Jason Lee at home talking to some woman who bears all the qualities the genre uses for uptight fiancés—short brown hair, bitchy wool sweaters, an un-curvaceous body. So Jason Lee goes out and sleeps with some adorable blonde hooker or whatever. As the drama unfolds, I fall in love with the fiancée, even though she spends the whole movie ignorant, stressing out over cakes and haircuts. She’s just furiously devoted is all, which I understand.

The plane lands in Los Angeles. As I wait for my father to pick me up, I consider two possibilities. The first is I tell him everything. In this scenario, he smacks the dashboard with his big hand. He says “don’t be stupid.” He’s twice divorced and lives alone in a house I haven’t seen yet. He tells me I have to confront Helen. “Confront,” he keeps saying. Later he’s calmer. We are sitting poolside in the twilight, drinking beers, commiserating about loss. He says something amazing. He says that when you finally accept love is gone, you are declaring that it never existed in the first place, since a memory that endures cannot speak for a feeling that has disappeared. I feel better. I feel so much better.

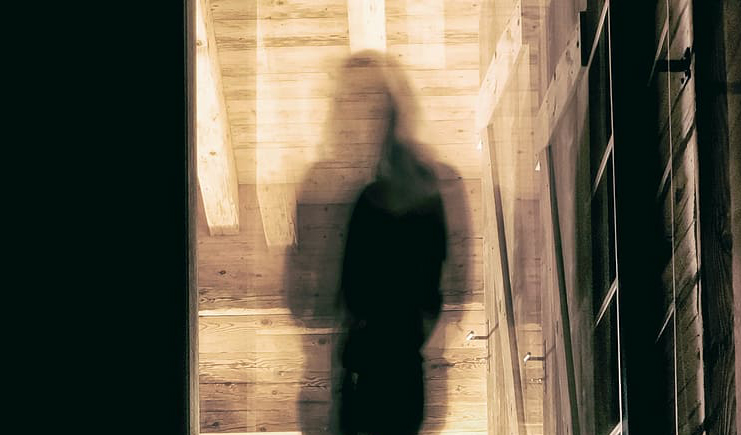

The other option is to not say anything at all. He shows me the remodeled bathroom and I say things about work. In the middle of the night, I eat cereal in a dim-lit kitchen that glows with the light of unfamiliar electronics. And when I walk down the hallway, I don’t recognize where I am. I think it’s my house, and that Helen is in the room I’m groping towards. We are together, and have come to a place where we find strength in conventionality. We are done asking for too much. We carry on if what we love begins to break in two. She keeps asking where we are, and I have to remind her. I am saying Kentbrook, Kentbrook, Kentbrook.

John Englehardt is a 4th year MFA candidate at The University of Arkansas, where he also teaches creative writing. His stories have appeared in The Monarch Review and The Stranger.