Reviewed by C.L. Bledsoe

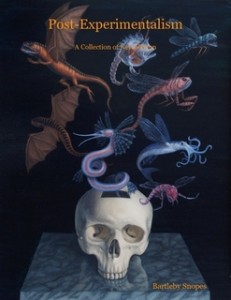

Bartleby-Snopes: Post-Experimentalism

Nathaniel Tower, managing editor

Bartleby-Snopes publishes stories, poems, interviews, and reviews, each month at www.bartlebysnopes.com. This is a special print issue focused on post-experimental writing. The issue includes stories and brief statements from the authors explaining their relationships with post-experimental writing. Post-experimentalism seems to differ from experimentalism in that post is more concerned with being entertaining, though it does still experiment with form, style, etc. According to Stephen V Ramey, “The very best stories, to my way of thought, invent technique to suit a story, and not the other way around” (pg. 22). Lauren Stone says, “By presenting narrative that can be interpreted in multiple facets the author forces the reader to engage with the text to inform meaning” (pg. 22). Both of these statements ring true, though they do little to differentiate post-experimentalism from experimentalism.

The issue begins with Christopher James’ “Sweet Enough,” a story about three friends who like to hang out and complain. They don’t like each other and pick each other’s foibles apart, but clearly, they’re driven to each other out of desperation: who else would hang out with these judgmental people? The opening scene has the girls getting snacks from “the douche-bag Indian man at the store” (James, pg. 7). As they’re tearing each other and other kids down, they don’t notice as “the douche-bag man lit himself” (7). His motivation is glossed over, though we find out the Indian man might have acted inappropriately with one of the girls, though it’s just a rumor. It’s glossed over because these girls don’t really care about him or her; their only real concern is absolving each other of any responsibility or guilt. As the story progresses, the girls refuse to take that responsibility; they refuse to grow.

“The Tricky Composition,” by Hall Jameson, tells the story of Walter, who has somehow found himself inside sheet music. He’s on a G-clef, to be precise. Walter doesn’t exactly remember how he got to this place, but as his memories return, he begins to search for his wife and to seek out clues to a murder. It’s an interesting, playful story that starts to get at this idea of post-experimentalism. Jacqueline Doyle’s “The Last Metaphor” follows a writer who attempts to quantify every experience in metaphor, even his death.

“A Story in Which a Teenage Boy Falls in Love and Is Subsequently Affixed to a Bench in the Park,” by Justin Bostian, is one of the best examples of what the editors and authors seem to mean by post-experimentalism. The title pretty much tells us the story. The author comments on the form and approach with lines like, “Jeffrey was fond of speaking aloud, both because he had a small but growing tumor in his frontal lobe…and because it helps the narration of this story run smoothly” (Bostian, pg. 44). His tone is humorous and playful.

Most of these stories are quirky. They experiment with form, at times, in their arrangement. Some comment on the form or approach itself, though often in a playful, non-invasive way. For me, the best of these stories are the humorous ones, and throughout, I get the impression that these authors don’t take themselves too seriously, which would be the death of these stories.

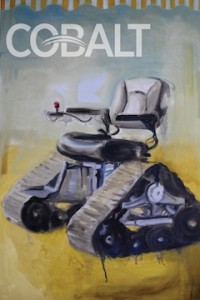

Cobalt, Volume 1.

Andrew Keating, managing editor

Cobalt is a new online journal housed in Baltimore, located at www.cobaltreview.com. This print issue is an awards issue, collecting the winners of the Cobalt Fiction Prize, Nonfiction Prize, and Poetry Prize, as well as two finalists for each, along with a selection of, presumably, the better fiction, nonfiction, and poetry from the year and excerpts from the Cobalt Interview Series.

“Modern Jazz Parade,” by Sandra Hunter, is the fiction winner. It tells the story of Basem, a Syrian teenager who endeavors to join the army. The sounds of war, often not far from his home, make him dream of “Noo-Allins, U.S.A. Dixie-music,” (Hunter, pg. 1). Basem’s friend Ziad already joined, and Basem is jealous. But his father and Basem’s unconventional family, including an orphan and a refuge who work at Basem’s father’s restaurant, want Basem to go to college. As the army’s abuses of Syrian citizens become more apparent, Basem must choose between his best friend and dream, and his father’s plans.

I can see why this story won; the setting and characters are different from the usual literary journal fare. The writing, itself, is a very close third, which can be choppy at times but also stands out. The story’s ending is inevitable, and perhaps predictable (aren’t the endings of good stories always inevitable?) but Hunter does manage not to soapbox while exposing the plight of these people. But more importantly, Hunter just tells a good story.

Probably my favorite story in the issue, and one I’ve read before, is Dave K.’s “How To Adopt a Cat” now collected in his excellent Victorian steampunk book Stone a Pig. The story is a portrait of Victorian poverty; a man has recently been released from an institution and sets about restarting his life. It’s well-written, entertaining, and has the feel of a novel in a few pages, as any good story should.

Interview excerpts include Rick Moody, Matt Bell, and others. Jane Delury contributes one of the best lines, when she says, “There’s a chemical women secrete during childbirth that dulls memory. They forget the pain and the species continues. I’m convinced the same chemical is secreted in the last phases of novel revision.” (pg. 26).

There are several recurring themes throughout the nonfiction. Homosexuality and gay rights. Differing cultures. In general, the idea of “The Other” is prevalent. These are mostly memoir pieces, confessional, though there is one long essay on belief and its ramifications by John FitzGerald.

The poetry avoids narrative or confessional elements, for the most part, being more philosophical and idea driven, but, to be honest, there wasn’t much poetry. The focus seems to be much more on fiction and nonfiction. Keating and his editors have put together a solid collection, especially for their first year.

CL Bledsoe is the author of the young adult novel Sunlight; three poetry collections, _____(Want/Need), Anthem, and Leap Year; and a short story collection called Naming the Animals. A poetry chapbook, Goodbye to Noise, is available online at www.righthandpointing.com/bledsoe. Another, The Man Who Killed Himself in My Bathroom, is available at here. His story, “Leaving the Garden,” was selected as a Notable Story of 2008 for story South‘s Million Writer’s Award. His story “The Scream” was selected as a Notable Story of 2011. He’s been nominated for the Pushcart Prize 5 times. He blogs at Murder Your Darlings. Bledsoe has written reviews for The Hollins Critic, The Arkansas Review, American Book Review, Prick of the Spindle, The Pedestal Magazine, and elsewhere. Bledsoe lives with his wife and daughter in Maryland.