Ryan Bradford

The landing is awful. Our plane skids, wings tilt, the woman next to me pukes. “Sorry about that, folks,” the pilot says over the intercom. “The storm.” The only explanation he gives.

“Merry Christmas,” the flight attendant says as I deboard. She doesn’t look me in the eyes.

Dad’s car idles in the passenger pickup zone. Other passengers rush past me and disappear in the falling snow. A thick cloud of cigarette smoke chokes me when I open the door.

“College man,” my father says. I throw my bag behind me, noticing empty soda cans and fast food bags in the backseat. Dad lights up another cigarette, inhales half of it. “Tell me about school,” he says. “You learning anything?”

“Not really,” I say, and we laugh. The drive is silent and Dad drives slowly. There are few cars out on the road.

We pull into the driveway and Dad kills the ignition. In the dark, before I can open the door, he says, “I have to tell you something about your mother.”

* * *

My mother won’t face me. She stands in the corner, her face pressed hard into the angle. Her hair is dirty, wiry like a pencil scribble. The white nightgown she wears is now gray. Her ankles are covered in mud and coarse fur.

“Mom?”

She doesn’t turn around, but shivers and grunts three times. The sound is vaguely sexual. Dad had warned me about the grunting.

Huhhn huhhn huhhn.

“We’ve been going through some changes,” Dad says. “To tell you the truth, things haven’t been so good since you left.”

“It’s only been a few months,” I say.

“Actually, we’ve been having troubles for a long time,” Dad says. His voice breaks and he’s not quick enough to stop a tear. I drop my bag and take a step toward my mother. Dad grabs me by the shoulder, holds me back. “I wouldn’t right now.”

* * *

At dinner, my mother sits at the table with her chair turned away from us. Dad sets a bucket of fried chicken on the ground near her feet and she flaps her hands with excitement. She ravages the meat and flings finished bones off to the side where they leave grease explosions on the wall. My mother reaches for more, her hand swirling around in the bucket. I try to remember if she ate like this when I lived at home.

Dad takes out a new pack of smokes, tears the plastic off and lets it fall to the floor. He lights up. “When did you start smoking in the house?” I ask, and he says “Huh?” because my mother is grunting again.

* * *

I post up in my old bedroom and lock the door behind me because Dad tells me to. We don’t know where my mother is.

The bedroom makes me sad. It’s just an empty room with a mattress pushed against the wall. All my posters are gone. I’m not sure what my parents did with everything I didn’t take to college. I plug in my computer and chat with college friends until my mouth tastes sour.

The house is dark when I emerge from my room. I can hear Dad snoring on the couch. I flick the bathroom light on and flinch. What are these, 100 watt? Have my parents always bought such bright bulbs?

There’s a flattened tube of toothpaste and frayed toothbrush still in the medicine cabinet. The mint tastes so good I could eat it. With the toothbrush in my mouth, I lean out of the bathroom door and look up and down the hallway. All the family portraits have been turned around. My brushing slows. I lift one off the wall and face it toward me. In the photo, my mother’s face is scratched out. Foamy spit drips onto the glass. I clean it with my sleeve. That’s when I hear grunting at the other end of the hall.

Huhhn huhhn huhhn.

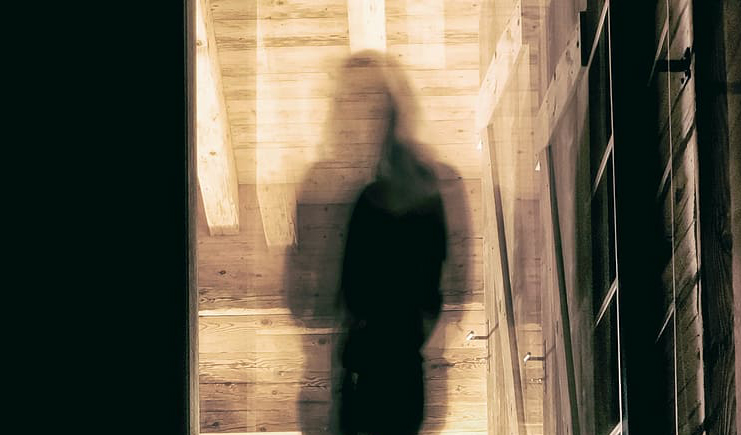

My mother stands in an open doorway, her back to me. Her gray nightgown shakes like a dim phantom in the darkness. The glass cracks in my hands.

“Mom?” My voice is thick with toothpaste spit.

She takes a step backward.

“Mom,” I say again.

She runs at me, backwards, high-stepping and flapping her hands above her head. Her grunting turns into choked laughter.

I drop the picture frame on the floor, jump into my room, and lock the door behind me. She bangs on the door, scratches at the wood. Her laughter fades as she runs to another part of the house. The toothbrush is still in my mouth. I set it on the dresser and swallow what’s in my mouth.

* * *

Three months prior, my mom had driven me to college, a twelve-hour drive. We listened to David Sedaris on audiobook after she called my music “too heavy.” We ate Wendy’s for lunch and Denny’s for dinner, where she ordered brinner and that inspired me to order a breakfast dish too. My mother’s eggs came over medium, even though she asked for sunny side up. She poked the yolk and the sludgy, viscous innards soaked her pancakes and hash browns. Then she started to cry. I looked down at my own plate, embarrassed. When she was finished, I asked if it was because they got her eggs wrong and she laughed. “I’m going to miss you,” she said, and then she ate ravenously.

* * *

In the morning, there’s a dead rabbit outside my bedroom door. The innards make a pile. Our hallway is graffitied with blood.

“Dad,” I say, shaking him awake. I tell him about the dead rabbit.

“Oh, yeah. That’ll happen,” he says, lighting up.

* * *

Dad takes me to the mall for dinner. We can’t find mom, but neither of us is really trying. “Looks like it’s a dudes’ night out,” he says loudly, and it sounds put-upon. Like he’s delivering a line.

The mall is packed with last-minute Christmas shoppers. Dad hands me a twenty and says to get what I want. When we reconvene in the middle of the food court, he’s got Panda Express and I have Sbarro.

“Classic,” he says, nodding to my slice of pepperoni.

We eat in silence. I sneak glances at him, trying to seal his features in my mind just in case he ever turns like Mom.

“Don’t get me wrong. I love your mother,” he says, unprompted.

“Okay.”

Dad opens his mouth to say something and shuts it. He stabs his plastic fork into a piece of broccoli and the middle tines break off.

* * *

On Christmas morning, I wake up late. There’s no music playing, no scents of breakfast, but has there ever been?

In the living room, my mother is sitting in front of the tree. Her back is to me, but I can tell she’s playing with something in her hands. She’s grunting to the rhythm of Jingle Bells. The tune sounds thick, blocked by whatever she’s chewing.

“Mom?”

My mother stops grunting at the sound of my voice, and cocks her head to the side. She slowly rises to her feet and drops her hand to the side. A piece of meat falls on the floor, leaving a blood stain. Only now do I realize how rotten it smells in here.

Huhhn huhhn huhhn.

“Mom, where’s Dad?”

She starts to turn around. I resist the urge to look away. I need to see her. For some reason I say “I’m sorry.” She turns, keeps turning.

When we’re finally facing each other, I can tell that she doesn’t recognize me, either.

Ryan Bradford is the author of the novel Horror Business, as well as the founder and editor of Black Candies. He is the winner of Paper Darts’s 2015 Short Fiction Contest. His writing has appeared in Vice, Monkeybicycle, Hobart, New Dead Families and PANK. Follow him on Twitter at @theryanbradford.