Julia Dixon Evans

Theo’s night terrors began when he was a toddler, but this is the first time it’s happened when I’ve tried to sneak a man into the house overnight.

What if, when we’re sleeping, we are the purest versions of ourselves?

What if, when he’s sleeping, Theo is the purest version of himself?

What if.

I met Grady on the haunted trail, with Theo, age 10, clutching my hand, somewhere between standing behind me and wrapped around my side.

“Excuse me, miss,” he said. “Does your son want to see the chainsaw?”

I laughed, because no. No, thank you. We don’t want to see your chainsaw. This was a terrible mistake. Theo’s friends are all old enough to handle this shit, but apparently he is not. Apparently I am not.

“Come on backstage. I’ll show you.”

“Not helping,” I said, and I kept moving.

Grady laughed, kind of sweet and humble, which betrayed his costume: white coveralls, glowing a cool blueish purple in the blacklight, a hockey mask, and red-dyed corn syrup smeared artfully over everything.

“I mean, I can show you how it’s a prop. It’s totally empty. It’s pretty cool how they make these,” he said. “It’ll help, I swear.”

“Everyone knows they’re fake,” I said. “Come on, Theo.”

“I want to see the fake chainsaw,” Theo said.

Which is how I ended up “backstage” in a haunted trail, which isn’t really a trail, nor is there really a backstage. More like I was suddenly in Grady’s trailer, a man covered with blood and a Jason mask and holding a supposedly fake mauling device. Grady opened the door, ushered us in, and removed his mask. He wasn’t too bad to look at.

“I’m Grady. Nice to meet you, Theo.” He didn’t pay much attention to me, which I appreciated at first. Then it started to hurt a little. Then it started to annoy me. Then on the way out, he whispered, “I want your number,” so I wrote it down for him on the back of my haunted trail ticket.

It had been over a year since Theo’s last night terror, and a complacency I didn’t notice set in. A normalcy. My son is normal! I am a normal yet lonely mother. I am getting sleep. Not enough, but some. This is all fine.

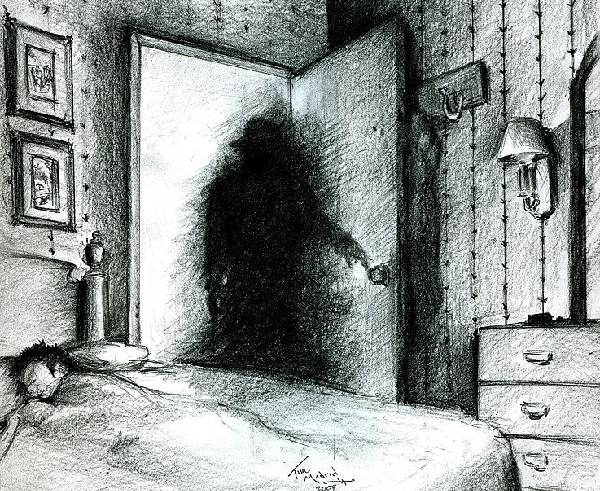

But two weeks after the haunted trail, Theo’s chilling screams and cries woke me. My mind still cloaked in a sleepy fog, I rushed to his room, elbows banging against doorframes, stepping on Legos.

My thoughts as I ran down the hallway: Oh god, what if he fell off the bed and broke a bone? I’m going to have to take him to the ER, call in sick to work tomorrow, and what if he puked or pissed the bed and all of the spare sheets are dirty in the hamper? I just wanted to get one decent night of sleep. By the time I opened his door, the hall light washing yellow on his vacant stare, mouth wide open, earsplitting noise, I even had time to feel ashamed of my selfishness before I remembered: night terrors.

It was the worst I had seen it. I sat down with him and did all the things you’re supposed to do, which mostly equates to nothing. There’s nothing you can do. Spit flew from his mouth and dribbled onto his lap. I held his shoulders away from the wall—as best as I could—while he thrashed his head from side to side.

The next morning I woke up on Theo’s floor, my son poking at me with his toes.

“It’s 8 o’clock, mama,” he said, bright and singsongy. “Aren’t we gonna be late?”

The next night I felt incapable of sleep, but I woke up on Theo’s floor again. The third night I couldn’t sleep at all, despite three nights of sleeplessness, of fresh terrors. I sat up all night in my own bed, my eyes stinging from the mix of insomnia and TV screen, watching reruns on TNT. First it was Alias. Then it was Everybody Loves Raymond. By the time the old movies started up, I must have been nearly catatonic because I don’t remember the movie, only thinking it was normal that my ten-year-old son shuffled across the room, eyes open, between the foot of my bed and the TV on the dresser. He pressed his palm flat against the wall, then lowered it slowly to his side, shuffled himself back around, and left my room. He stopped right outside my door and shouted, something between a roar and a cry. I got out of bed, put my hands on his shoulders while he screamed at my face, his eyes wide, vacant, dilated pupils pure black. And maybe I had avoided his eyes for ten years of sleep dysfunction, but I never noticed the black before.

Back In my room, I closed my eyes and walked toward the wall, placing my hand against the spot he touched. I shivered. The cold gray light of morning began to sweep across the room. I switched the TV to a morning news show. I never slept.

And now I’m locked in my bedroom, already regretting sneaking a man into the house while Theo sleeps.

“Oh god, baby, I’m gonna come,” Grady says as his body stutters in and out of mine. I dig my nails into his back. How can he possibly call me baby the first time we’re doing it? I am nowhere near coming, and this isn’t helping. “Oh yeah, baby. I like that, baby.”

Theo’s scream stops Grady’s “gonna come” quite immediately.

“What the fuck.”

I jump up and wrap my bathrobe around me. It’s old terrycloth, more yellowy grey than pink, and if not the fact that I’m a single mother, if not the fact that my child’s night terrors interrupted sex, then this bathrobe will be what finally makes Grady give up.

“Just, hang on a second. Don’t follow me. I need to deal with this,” I say. I stare at him for a second. Theo groans, loudly, and I can hear it from two rooms over as if his strawberry toothpaste breath were right against my ear. “You can leave if you want,” I tell Grady.

When I walk in, Theo is sitting up in his bed, clutching the sides of his feet with his knees splayed out to the side, like yoga. He’s spitting, frothy, with every staccato squeal he’s making, and this Morse code sounding thing is new. I’m about to sit at his side, like always, and hold him as best I can by the shoulders. Instead, I place my palm flat against the middle of the wall, the way he did a few nights ago. At first I don’t notice I’m doing this. I don’t want to do this. I gasp out loud, and Theo’s face snaps toward mine. His eyes are open, pupils large and black, and he’s not seeing me. He’s not seeing me. I swear he’s not seeing me.

I stumble backward, out of the room, and slam his door shut. I lock it from the outside—I had to install locks on the outside when his sleepwalking was particularly bad.

I fall back against the door and slide down, sit on the floor, knees to chest. I hope Grady’s left. I hope this night ends soon. And then, and I swear to god I heard no footsteps, I hear the doorknob rattle above my head. I jump to my feet and it rattles again, repeatedly, incessantly, violently. I run down the hall to my own room, slam the door shut and lock it behind me.

Grady is gone, nothing but a ripped condom wrapper on the nightstand in his wake.

In Google, on my phone, I type without thinking: possession in children. I get drivel, so I type possession in children night terrors, and before I hit SEARCH, I add demonic.

The results are a mix of bullshit and terrifying. I can still hear Theo’s door handle rattling.

I wake up curled on the floor with my phone under my cheek, battery drained. The sun is up. I can hear Theo’s regular voice.

“Mama! Let me out! Mama! I have to pee super bad!”

I unlock our doors, mine and his. Theo scurries to the bathroom. When he emerges, I force myself to look at him. I make breakfast, toaster waffles and sliced banana, and I’m afraid of him. When I bring myself to look at him, I can barely look away, that no-sleep, stinging-eyed stare.

The next night it happens again. This time he manages to bust through the lock on his door handle. He stands outside my bedroom door, rattling the handle of my locked door. All night. When the sun comes up, the rattling stops. I wait a minute and peek outside. I find him in his own bed, asleep. His door is open and unlocked. The handle seems unscathed.

“Mama, can I sleep in your bed tonight?” he asks me this evening.

This is textbook nighttime parenting. I can do this.

“Sure, honey. Of course.”

I tuck him in on the empty side and lie down next to him. I think of the devil. I think of entire ancient villages torched by the child possessed by the devil, screaming vacantly through the night. Or maybe the torching happened by the other villagers, afraid of the devil. Afraid of the child. Theo reaches for my hand and I flinch.

“Sorry, Theo,” I say, picking up his soft little hands, dirt beneath his fingernails. I kiss his knuckles, my eyes closing, and all I see in my mind is his eyes when they’re black. “I think that haunted trail scared both of us,” I finally say.

Theo is almost asleep, his eyes closed and fluttery, and he murmurs, “I’m not scared,” and it’s the scariest part of all.

All night he’s quiet. Silent. I do not sleep.

The next night: not a peep.

On the message boards, I’m mamatheo79. It’s 2 a.m. and I’m reading a thread on Reddit about demons, and a text scrolls across the top of my phone. It’s Grady.

Sup, he says. Happy Halloween.

I briefly check to see if my phone has a chainsaw emoji, but it doesn’t. I don’t reply. I click back to the thread. All I do is wait for another night terror. Another night where Theo with his black eyes and his hand against the wall and his hand on the door handle, rattling, rattling, rattling.

“Mama,” Theo says. “I wanna go trick-or-treating tonight.”

I panic. Halloween is where we can’t tell the difference between the costumes and the ghouls and the witches and the demons. Theo can’t know this. My son can’t know what I think, how I no longer sleep except in stolen bits and when I wake I hallucinate about demons and Hell and pain. Am I hallucinating?

When night falls, Theo is dressed as an elf. His eyes are blue. He takes my hand the way he used to when he was little, and we climb every set of steps on our street, collecting Nerds and Tootsie Rolls and Twizzlers. At the next-to-last house, he stops, tugging on my hand.

“Mama,” he says. “I remember everything.”

“What’s that?”

“I remember the dreams.”

I freeze, short of breath. I close my eyes.

“Mama,” he says.

I used to love the sound of my name in his little-kid voice, but now I don’t sleep and now he’s the devil and I don’t want him saying my name.

Theo takes a deep breath and says, “I’m okay.”

I look at him, dressed as an elf, and he’s just a boy, my boy.

“They’re just bad dreams. They go away when I wake up.”

His eyes are closed.

“I’m okay, Mama.”

Julia Dixon Evans is author of the novel How to Set Yourself on Fire, forthcoming in May from Dzanc Books. Her work can be found in Paper Darts, Barrelhouse, Pithead Chapel, Tyrant Books, and elsewhere. She is an editor and program director for the literary nonprofit and small press So Say We All. More at www.juliadixonevans.com. Follow her on Twitter @juliadixonevans.