Shane Cashman

We argued over the obituary every day for the better part of a year. The State hired us to write the announcement, holed up in a conference room—dry-erase boards, legal pads, maps, pencils, encyclopedias, that sort of thing.

“How’d we get here?” someone asked at the start of most meetings. Here had multiple meanings depending on the mood of the day. Some days it meant, “When was the planet born?” or “How did the planet die?” or “What the hell are we doing here, pissed-off, blank, unable to sum up the thing?”

There were camps of us that thought the things other camps nominated as the start of the planet were in fact the things that ended it.

Another ‘how did we get here’ went around the room.

Cosmic fizz, no, cave-sex, no, comets, no, bacteria, no, the A-bomb, no, Allah, Moses, Hitler, Elvis, Mary, Jesus, Google, no.

Bursts of light pulsed in the distance from the conference room window because the sky was a back and forth of hollow-points and hell cannons and car keys and lit cigarettes and body language and crucifix and avocado pits and feral cats and hot coffee and Christmas trees and money shots and gut reactions and themselves—they were throwing themselves, too.

Someone asked what, if any, sleaze should be included in the obituary. Someone else asked why’d we want to immortalize the bad parts. Someone said you know they called Elvis fat in his obituary? Someone else asked, but maybe this could be for the part where we say, however briefly, what the cause of death was? But what if, someone else said, this is a symptom leading up to the death and not the death itself? Someone else said what if death is a series of deaths and this is one of many?

One night, in our row of cots, a pink-eyed woman who never changed her clothes for bed, paced from cot to cot asking if we knew why the Earth was the only planet not named after a God.

People were outside screaming latitudes and longitudes for targets louder than people singing Happy Birthday louder than the bagpipes louder than people reciting Yizkor louder than people reciting from the Mahabharata louder than Duas sung into the salt-wet palm leaves. I was glad I couldn’t see my house from the window. If my children hadn’t seen me in a while, maybe they’d get their mother’s gift of not obsessing over doom. I used to dig a shallow hole in our yard once or twice a week and scream into it all my filth and kick the dirt back over and pray my screams would eat their way through the planet’s core. When I told that to the State, they hired me on the spot.

“Can’t we find something good to say?” someone asked.

Yeah, like denim, saltwater, futbol, donuts, The Louvre, amoebas, the heat of the sun on a cold spring day, paved roads, orgasms, most mothers, toothpaste, sunflowers.

We spent a month debating whether the dinosaurs should have more paragraphs than the humans or any paragraphs at all and vice versa. We argued about how much space on the page should be between the Neanderthals and ourselves and, say, the troglodyte and the pterodactyl.

There were camps that fought against a linear obituary in favor of one that would bring the planet’s historical and geological landmarks side by side, as if they were all happening at once, like the moonwalk next to the holocaust next to Pangaea next to the very first bees next to the Crucifixion next to blue-eyed Gautama next to aerosol next to the fart of the collapsed star that eked out early life next to Blind Willie singing “Dark Was The Night”…

How much should each space between each paragraph symbolize in time passed? Decades, centuries, days, seconds, millennia? We couldn’t even agree on the year we were in, so nailing down a death date was impossible. We kept several different calendars—solar, lunar, fiscal, not-safe-for-work. Depending whom you asked it was the second, third, fourth, or fifth millennium, or the four-billionth-year, the eighty-billionth or the five-hundred-billionth or there were no such thing as years. Should we leave a giant white space at the front of the obituary to suggest ice age or new life? And a bigger white space at the end for the next big thing to continue it? Others started to see the obituary as a series of short obituaries inside a much bigger obituary. They studied ram horns and whirlpools and hurricanes and nautiluses and fingerprints and Protoplanetary disks and the toilets flushing in the restroom.

We’d reviewed footage of dead in some red and dark street, headless, and our camps were teeth-gritting over whether these dead were heroes, gods, martyrs, evil, children, fathers. It felt dumb, but I asked the room if the planet only looked dead because maybe we’ve over-dosed on the old days, childhoods, if you had one, to the point that the evils we’re aware of now outweigh the evils we didn’t appreciate as children, that on the edge of our memory are those same dead stacked in the same streets. “Shut up,” someone said, sharpening a pencil.

I found myself writing obituaries after hours for people who, far as I knew, were still around. Everyone else was sidetracked, too, trying to stretch the obituary into their own love song or protest or self-portrait.

When the State asked to see our progress, we were all fired. A new cut of contributors took our cots, each one as sure as we were a year ago, not yet hunched from the work—all eager, creases, clean, young.

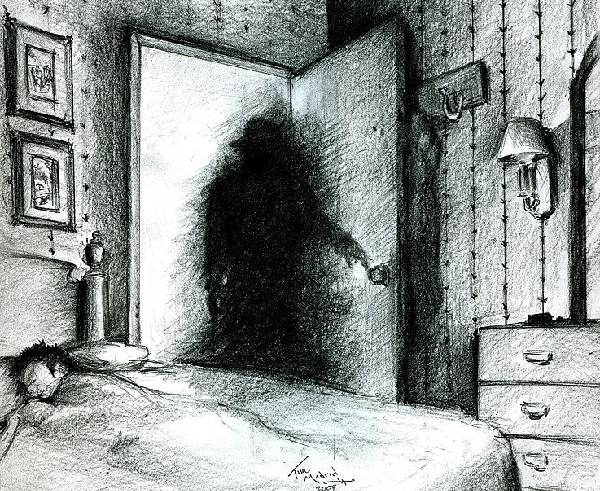

And I go chanting from memory on my back in the street like an open casket, petitioning the next big thing to come knock on the roofs so I can say, yeah, good luck with all that shit.

Shane Cashman’s stories have appeared in Catapult, Narratively, Vice, Salon, The New York Observer, Vol.1 Brooklyn, Fiction Southeast, and elsewhere. In 2015, he was the winner of PEN Center USA’s flash fiction contest. Shane currently teaches creative writing at Manhattanville College in Purchase, NY. Find him on Twitter at @ShaneCashman.