Chloe N. Clark

He calls you up only late at night, after you both should be in bed, and never when you expect it. Not your birthday or his. Not the anniversary of the game. But on random remembrances of things he thinks are worth celebrating. Once on a Sunday in May because he remembered you had both passed a tough class that day, years and years ago.

“Fucking weed-outs, man. You remember how much we studied for that thing? I saw those formulas in my sleep!” His voice was still exclamation marks, punchlines, a sense of someone shouting into the void just because they thought it might echo.

You always laugh along, fall back into the rhythm of your friendship. Once your wife asked how you’d met. And you didn’t remember: a class or tryouts, most likely. But you did remember the first time you thought of him as your friend. In a class, a girl was talking about her dog. She’s named Deneige. That means of snow, in French. Cuz she’s white! and he’d looked at you and said “I wish my name meant something, people take more time naming their dog than my parents took for me.”

And you laughed, but you weren’t sure if he was joking. But he smiled, widened his eyes as if at the shock of everything. The indignity of it all. Take my life, please. That was his joke. Over and over.

Sometimes you don’t talk for months and months. You’re never the one to call. His number changes often. He doesn’t like holding on to things, he says, and so you always pickup unknown callers. How many hours of spam have you sat through because you thought it might be him? Did you know your auto insurance is about to run out? Have you talked to your loved ones about a living will—the time is now? NOW. NOW. NOW. Once you missed him, asleep after the birth of your first child, unexpectedly early, and he left a rambling voicemail. “I’ve been thinking about you all day, man. Like I should call you. Like something big was happening. Remember before Liam? How I said something was about to happen? How could I have known that? Maybe that’s the thing, right, I’m always expecting something. Pity the unfortunate teller.”

At your wedding, he said he’d make a toast. But he never did. Your wife breathed a sigh of relief. You wondered what he might have said. You asked him, both of you taking a break from the crowded reception hall and everyone dancing, to lean against the cool of the back of the building, why he didn’t make a toast and he laughed, shook his head, said, “I’m working on being quiet.” Then he pointed across the street, towards the park, and a basketball court. Neither of you said anything, just walked over to the empty pavement in the dark. No balls were out, so he found a hedgeapple on the ground and you took turns passing it back and forth, taking shots at the hoop. It was much harder somehow to shoot something so much smaller. As if only the basketball had been made for your hands. Each miss, a thud of the hedge apple against the ground. A reminder of walking to classes, up the hill at the center of campus. and the hedge apples always everywhere, rolling around, hoping to trip someone up. When you were feeling lazy, you’d pick one up as you walked, study it instead of where you were going, and if your feet didn’t remember, the muscle memory of steps to class, and you got lucky, you’d go to the wrong building, have an excuse for being late. Thank the hedgeapple, as you set it outside the door.

The day before the game you won, the one that might have changed the courses of all of your lives, had it not been for fate coming up just a few weeks later, he showed up at your apartment door. You lived just off of campus, a walk away from every class and every good bar and not so far away from the local public court. It wasn’t so unusual for a teammate to swing by, ball under an arm, so that you could go play some horse. But he didn’t have a ball, just a look on his face like he’d been through war. You asked what was wrong, but he said nothing. So you took a walk together, to the lake, and sat on one of the docks. It was cold enough that no one was there—though in summer, spring, even late fall, it would be bursting with students and townies and everyone dreaming about the sun off the water. He picked a pebble up and skipped it across the surface of the water. “Give it four and a sink,” he said. You counted the skips. One. Two. Three. Four. And then it dipped under the water. You smiled, like you might have at a magician’s trick when you were small enough to not have known how it could be done. “I think we’re gonna win tomorrow,” he said. But he sounded so sad that you thought he was playing at sounding brave, that he didn’t believe it. But you did win. That game.

You wondered sometimes if he had felt like you did, as if you had been at the very edge of something vast. He had been there and you had been there. The game then the win then the world in front of you, so ready to let you be something big. If the championship had been won. If the draft had gone in your favor. If you could stand in front of a roaring crowd and hear them chant your name. If. If. And instead there was none of that. Just an injury and a loss and a slow shifting of your life into something else. Not smaller but not the same either. There couldn’t be many people who had felt the exact moment their futures changed. But you never asked him and he never asked you, and it hung between you both like a compass that could only point to things that might have been.

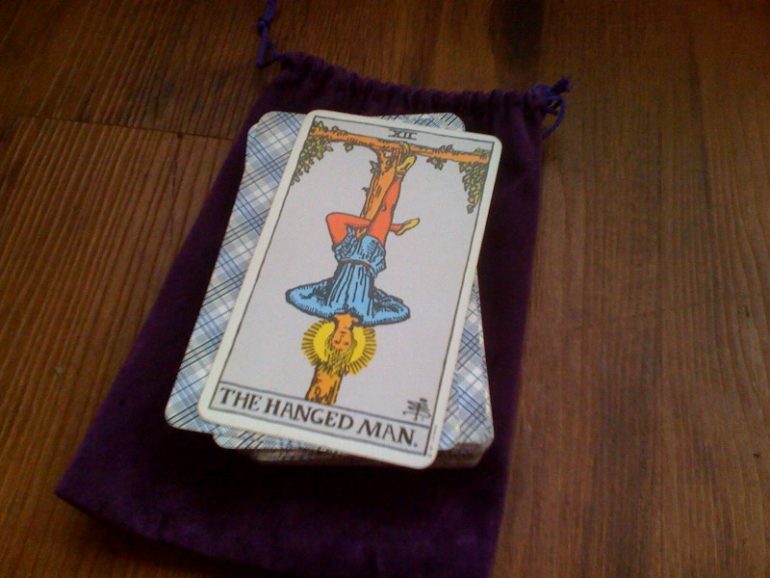

When your daughter is twelve, she asks to go to a fortune teller for her birthday. Your wife rolls her eyes so hard you think she’ll hurt herself, so you agree to be the one to go. The fortune teller spreads out tarot cards, flipping them over with a light boredom. When she flips a card with a man hanging from one foot, his expression not hurt or scared but almost wistful, you ask what it is. The Hanged Man. But you mishear it as The Hangman. It can mean surrender or being stuck in a loop of time. It reminds you of him, even the name. On the team, he could switch roles with an ease, never playing just one position. “It’s why I’m on the bench, Coach needs to know what is needed before he calls me out to play.” Your daughter taps the card, asks if its bad, and the fortune teller says, it depends, sweetheart, it depends.

In the locker room, before the Final Four game, after you all knew your chances were slim, your star in the hospital, nobody coming to save you, there was a hush. You all were about to decide if you were going into your church expecting a funeral or hoping for a wedding. He said, “we still gotta play like we think we can win,” and stood up and walked out. And everyone followed him. And it wasn’t a pep talk, not close, but it was something. And so everyone played as if they believed and it wasn’t a win, but it was better than anyone expected. A heartbreaker, the papers said. But it wasn’t. It was a miracle, the bride never ran away, the sun came out, everyone danced at the end of the night.

He calls you late at night because he says he can’t sleep. But you’re always up, too. So maybe it’s that nobody knows how to stay asleep anymore. Maybe it’s the news. Maybe it’s memory. Maybe it’s just the aches in your joints that get worse every year you get further from when you could shoot a three pointer and rarely see it miss. Sometimes you talk for hours, sometimes just a couple of minutes. Once, neither of you said a word, you just listened to each other breathing and you could feel time falling away, could see the campus and the lake and your friends all in the locker room shooting the shit, calling each other names, laughing. You all laughed so much that the sound could reach the court, bounce higher than a dribble, fly towards the nets.

One time, you tell him, about the tarot card, say it reminded you of him. He chuckled, “what a card to be like, huh? Some dude hung up to pay a price. Not the first thing you want someone to tell you it reminds you of them. Why couldn’t you have said a trading card of Michael Jordan?” And you laugh, too. You don’t tell him how you’d looked the card up. How some readings said it could mean sacrifice too. You don’t tell him how some nights you wonder what weight he tried to take on for you. Take my life, please, he always said. What offerings that fall through the air, waiting to be caught.

Chloe N. Clark is the author of Collective Gravities, Your Strange Fortune, and more. Her forthcoming books include Escaping the Body and Every Song a Vengeance. She is the co-EIC of Cotton Xenomorph, a lifelong fan of Rasheed Wallace, and a frequent tweeter at @PintsNCupcakes.