Claire Miye Stanford

CRYSTALLIZATION

The ice begins as a wrinkle at the edge of the lake, a threading of needles in the brush and the reeds. The slightest breeze will break its burgeoning corporeality, fracturing it into shards and then into nothing, causing it to rejoin the water, to resume that liquid shape. It is there, in body, at first dawn, and gone by sunset, straining to rebuild each night, crocheting itself around the edges of the land like a spiderweb, woven carefully in unseen corners, watchful, weary.

The ice knows it has been here before, in a past life. It feels a shudder down its spine, déjà vu. The shudder of a breeze that, this time, does not cause it to break. The surprise of survival. It gains confidence, clasps its neighbor, enlarges its reach.

Inch by painstaking inch, it turns the lake from liquid into solid, concentric circles closing in toward an indeterminate center, like the rings of a tree growing inward instead of out. The ice is growing stronger, but it cannot yet bear any more weight than a bird, on a break from migration. The ice tells the bird it must hurry, sending shocks of cold up through the bird’s feet.

A warning.

ACCUMULATION

One morning, the ice wakes to find that it has coalesced. The fish look up from the reeds where they make their home and see only a prism of light where they used to see sky. The ice is tentative at first, but then it begins to test its strength. It roars back at the wind, it laughs at the sun. It tries to shimmy and shake, to identify the weaknesses of its body, but it finds, to its delight, that it has none.

Only the ice knows the day it covers the lake completely; only the ice knows the day that it can bear more than a bird’s worth of weight. But humans will know soon; humans cannot help themselves. This the ice knows, too, somehow. Somehow, it knows the feel of human feet, the sound of human voices. Somehow, it remembers the approach of those first human toes, tapping its surface before every step.

The ice welcomes the humans. It opens itself to them. Skates and skis, ATVs and SUVs. Families with wool hats and rose-colored cheeks, frat boys drunk on Coors, joy-riding at midnight. Solitary beings who want, for an hour, to walk on water. The ice, too, feels full of joy, the pleasure of existing where it did not before exist.

Ice thick as cement and just as hard, a shock on the back of the skull, a cry. Ice that can sink ships, that can break bones, that can bring whole cities to a halt. The ice cannot help. It wishes it could. The ice does not like to be the cause of any pain.

SUBLIMATION

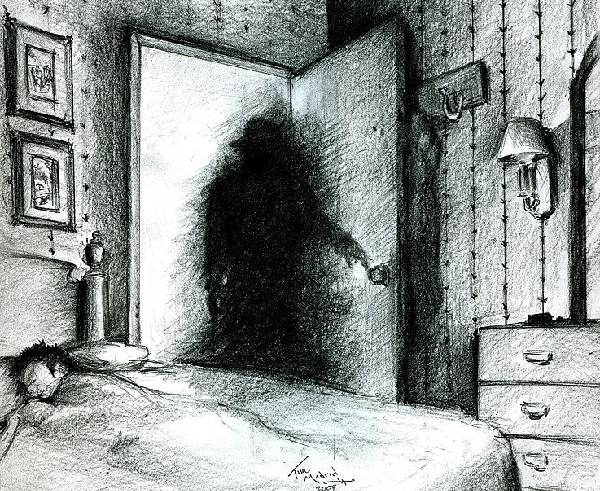

A day comes when the sun beats down, and the ice feels afraid. The fear is an instinct, deep-buried, but the ice cannot fight, nor can it fly. For months, it has withstood these rays, bathed in them, danced in them, shining like a disco ball. It had thought those days would go on forever, that it would go on forever, impenetrable. But a day comes when the ice begins to shed, to form thin slicks of water on its surface, minute puddles that do not re-freeze with fall of darkness.

A day comes and another day comes and another day comes, and the ice stops feeling human toes skating across its surface, stops hearing the human children exclaiming with shock and glee. It feels only a whittling, a calving, slow at first and then all at once, breaking into pieces that scatter like sea shells, that shatter like bones.

Come back, the ice thinks, come back to me. But it cannot stop the feathering of its body, its dispersal into air. The ice thinks of the birds, of how light they were, how free. The ice wonders if that is what it will feel like, when it melts into mist. If it will feel like flying.

EXTINCTION

There will come a time when ice will be only a memory. We will tell our children about the days passing into cold, about the clean smell of the air, its sharpness in our throats. We will tell them of the stillness and the quiet, the feeling every morning that the world had been remade. We will tell them of trips to the lake, of that wobble in our soul, the lift of fear and pleasure when we stepped foot on that which should be liquid.

When the lake is a dry crater in the land, both liquid and solid will seem like science fictions, stories passed down from generation to generation. And that is what they will become—legends—but we will tell our children that we were the ones, the last ones to know the feeling of ice on fingers, ice on wrists, ice on tongues.

We will tell our children what it was to glide, how hard the ice felt on our backs when we fell. We will tell them of its brightness, its blinding purity. We will tell them about the sounds of ice, the primordial creaking coming from below.

There is a wildness buried deep within us, too, we will say.

Claire Miye Stanford’s fiction has appeared in Black Warrior Review, The Rumpus, Third Coast, Redivider, and Tin House Flash Fridays, among other publications. She holds an MFA from the University of Minnesota and is currently a PhD candidate in English at UCLA. She is online at clairemiyestanford.com and @clairemiye.