Nick Story

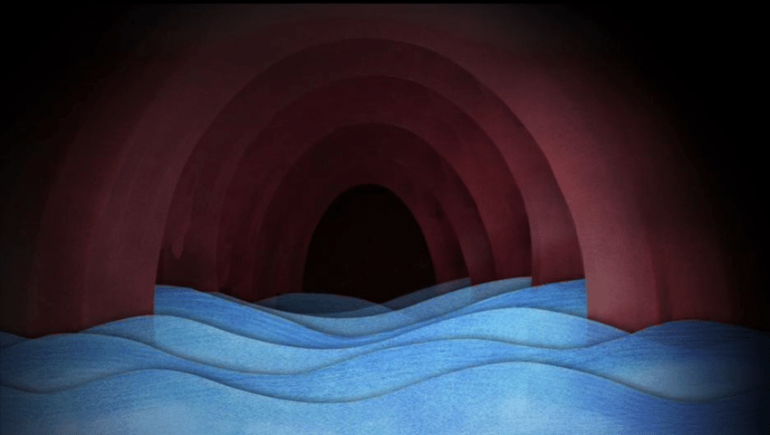

At around 11:00, Francine’s fifth-grade class walks single file across the soccer field toward the giant inflatable whale. She leads her students into the maw, red and ridged and hung with pink Christmas lights. It’s sticky inside and unseasonably warm.

“Where do whales come from?” Brice asks, voice echoing.

“The ocean,” Francine says. Her voice is hoarse. She hasn’t gotten much sleep.

“Which ocean?”

Francine only knows where this whale came from. The donor of the whale, John Ridgewood, had gone to Xavier Elementary and then made his fortune off the ocean. A frozen fish stick fortune. On the right fin there is a dedication in gold script: So that the children of the future might hold dear the mysteries of the Deep. John Ridgewood is now in prison for defrauding investors, Francine remembers.

Inside the whale, Francine tells her students to look up at the dangling baleen. She explains how blue whales eat. How they take a big breath of water, close their mouths, and push the water through the baleen, which filters out the krill.

“Krill?” Steven says.

“Very tiny shrimp.”

He looks thoughtful for a moment.

“Once my dad went to Lobster Palace and ate one hundred pieces of fried shrimp. It was his birthday party. The waiter didn’t let him have any more after that. He said it wasn’t safe.”

“Well, Blue Whales eat millions of krill each day,” Francine says. She’s not sure this is true but feels the need to say something scientific. She didn’t print the whale anatomy worksheets this morning and to be honest she’s sort of winging it. As the children explore the inner space, hopefully learning something, a wave of fatigue hits Francine. There are dark circles under her eyes. The pen in her cardigan pocket exploded, though she has not removed it. She remembers that she still technically has dinner reservations with Mark tonight, but these are no longer viable because Mark is on his way to becoming her ex-husband, and she won’t be going to any more dinners with him without a lawyer present.

Kids jump to touch the baleen. They move deeper into the gullet and see the realistic whale tissue. Francine forgets what all the parts are called. She wishes she had those worksheets.

“If you look up where the light is coming in, you’ll see two openings. Those are the blowholes. They are like our nostrils. They can shoot water forty feet into the air.”

The class goes ‘woo.’ Steven raises his hand.

“Yes, Steven.”

“How fast can they go in the water.”

“Pretty fast.”

“As fast as an airplane?”

“Sure.”

He nods. Omer is doing somersaults.

Mark could bring his new girlfriend to dinner. That’d be romantic. Just Francine, Mark, a couple of lawyers, and the new girlfriend. She seemed nice. Fifteen years younger. Blonde. Slender. Why wouldn’t she be nice? Her passion was experimental photography, but she also did weddings to support her art, he informed her, love in his eyes.

Francine gestures at the stomach, the kidneys. The children bounce around on the spongy floor. She wonders, not for the first time, whether there really is any educational value to being inside a whale.

Stuti, the dark-haired girl in glasses and a green dress, is hugging the lungs. “They are so small,” Stuti says. “Why are they so small?”

“They are small and collapsible to prevent an embolism when the whale surfaces,” Francine says. She seems to recall that language from the worksheet.

“I love the lungs,” Stuti says, and goes on hugging.

“Can you live inside a whale?” Hallie says. Hallie is wearing a plaid skirt and shiny dress shoes. There is something frightening about her. All of the children are a little frightening, but every year there is one child who is the most frightening and this year it is Hallie. Her father owns a car dealership and has the biggest, heaviest-looking hands of any man Francine has ever met.

“I don’t think so, Hallie.”

“The Bible says you can,” Hallie says. She looks defiant.

“Maybe you can then,” Francine says, not wanting to fight. And who knew. Maybe you could live inside them. For a little while. If you had good balance. And hung out near the sides.

“Not just maybe, Mrs. Fisher,” Hallie says. “There’s a story about it.”

“Well, if it’s in a story it must be true.”

“There’s too much stomach acid, Hallie,” Stuti says. “You’d be melted.”

“Not with the Lord helping you, you wouldn’t.”

Steven is kicking the gall bladder with his soccer cleats. Then Omer takes a turn. He kicks so hard one of his shoes comes off. Steven snatches it and runs. Omer and several other boys chase him deep into the whale.

Later, Francine would look up the photographer’s photographs online. A lot of color fields. Trash in abstract light. But one will catch her eye: a photo of an old man sitting down next to a grave. One hand is touching the stone. The stone reads MARY. The other hand is holding a flower, slightly wilted. It is called 50 years. At Francine’s age, even if she finds another person, she wouldn’t have fifty years left with them.

There’s a commotion near the liver. They are throwing a hat back and forth, over Omer’s head. Francine can tell what had begun as a game is now a real source of distress for Omer. She goes over and grabs the hat and gives it back to him.

Francine tells the class to gather round the heart. The whale heart is enormous with a crushed red velvet exterior. The other organs are just plastic. The heart is special. Francine strokes the soft surface, and a wave of sorrow grips her. All eyes turn her way. The children become quiet. They are expecting her to say something. They are ready for an education, and she is aware that this is her job, but she has very little useful information about whales.

She rubs the heart, feels the softness of it. She tries to remember the lesson from the year before. Something about the power of the heart in a creature of that size.

She hears the kids scream and she looks up. From the back of the tail a man walks out. He is dirty but kind looking. He has a gray beard and a brown leather jacket with patches on the elbows. His hair is slicked back.

“Beg pardon, Miss, children. I have made my home in this creature’s tail over the weekend. I hope you don’t mind me tuning into your lesson. I love to learn. What were you saying about the heart? I know a few things about the heart myself.”

“Who are you?”

“The name is Christopher Jimson, man of no residence.”

“Are you supposed to be someone the whale swallowed?” Stuti asks.

“Are you like Jonah?” Hallie said.

“I don’t mind you thinking of me like that, little girls.”

“Mrs. Fisher, is he part of our lesson?”

“What are you doing in here?” Francine asks.

“I’ve lived in many educational exhibits. For a long time, I would sleep in the History Museum downtown—in the Inuit display, right in the Igloo. And for a while I also stayed in the Frontier Log Cabin. But they beefed up their security recently. And for a while I lived in an apartment with someone I cared for, and I liked living there with her plants and the rain, and hearing her footsteps, but she decided that I was strange, and told me to leave one day. And I lived on the street for a long time, but that was difficult, because the moment I’d get settled in a park or at a bus stop, someone would come along and tell me to move. And so, I’ve been moving, all these years in constant motion. There’s a freedom in it, but it is a lonely freedom. Wandering takes its toll on the heart.”

“Even a whale’s heart?”

“I suspect given its size the whale feels even more than we do. Imagine what it loves in that big mysterious ocean. There is more to love there because there is more there, much more, than on land. But that also means there is much more to leave behind, to lose. Can science tell us what a whale has lost? I don’t think so.”

“I’m going to have to ask you to leave,” Francine says. “This is school property. And we are in the middle of a lesson.”

Christopher Jimson walks over to Francine and touches her shoulder gently. She quivers.

“Children. Look at the ink in her pocket here. And in her eyes. You can see it. Your teacher has known sorrow, known loss. This is what it looks like. It’s good to know it when you see it. Be nice to your teacher. Someday you will know these things, too.”

There is something about his moist bloodshot eyes that Francine recognizes. It’s as if she has seen them before, in another life where he was very important to her. But she is probably just tired and imagining things.

“You smell like garbage,” Steven says.

“This is something that happens to people. Eventually you stop smelling good.”

“Leave or I’ll call security,” Francine says.

“Let me at least hear about the heart before I go. I still desire to learn.”

“Let Christopher stay, Mrs. Fisher.”

“Please. We like him.”

“They like me,” Christopher Jimson says, beaming.

“You were explaining about the whale’s circulatory system,” Stuti says.

“What is inside the heart, Mrs. Fisher?” Steven asks.

“It’s where the soul hides,” Hallie says.

“No Hallie,” Stuti says. “It’s tissues and valves.”

“That is deception,” Hallie says.

“You are deception,” Stuti says.

“Mrs. Fisher, your eye make-up is running down your face,” Omer says.

“Is Christopher part of the lesson?”

“What’s in there?” Steven says. “Are we ever gonna get to see?”

“It’s just air,” Francine says. “Do you want to see?”

She takes the pen from her shirt pocket. She raises it and quickly stabs the heart. Air comes shooting out of the hole, a pent-up hurricane that blows her hair backwards and knocks Omer over. They try to run out of the mouth but the whale collapses on them almost instantly. They are stuck under the heavy plastic. The forms in the plastic shriek and yell for help, except Francine, who lies still, held quiet in the dark collapse. She could almost sleep.

The janitor witnesses the collapse from his special custodial shed. He puts out his cigarette and runs over the field toward the deflated whale. He has a tool for cutting the class out. It’s not the first time something like this has happened.

Nick Story is from Columbus, Ohio. His fiction has appeared in The Indiana Review, The Common, Molotov Cocktail,and The Café Irreal. He has an MFA from the University of North Carolina Wilmington.