Lindsey Godfrey Eccles

It hadn’t rained for a month on the day the wolfchild came. Our cisterns were dry, but we dared not burn timber to draw salt from the water that surrounded us on every side. We would need those trees for the coconuts they bore. By the day the wolfchild arrived, the fruits of the palm had long been harvested, the birds’ nests were eggless, and so long as the angry sun beat down we lacked strength to hunt fish in the shallows.

When dusk fell over the island, I settled my infant into a crèche of palm fronds woven by the aunties for the children of our clan. Soon she slept snug against the fur of her cousins.

I went to forage mollusks on the sunrise side of our world, but when I arrived at the inlet no one was hunting food. Everyone was staring at something red bobbing on the waves. I joined them, wondering if it might be good to eat.

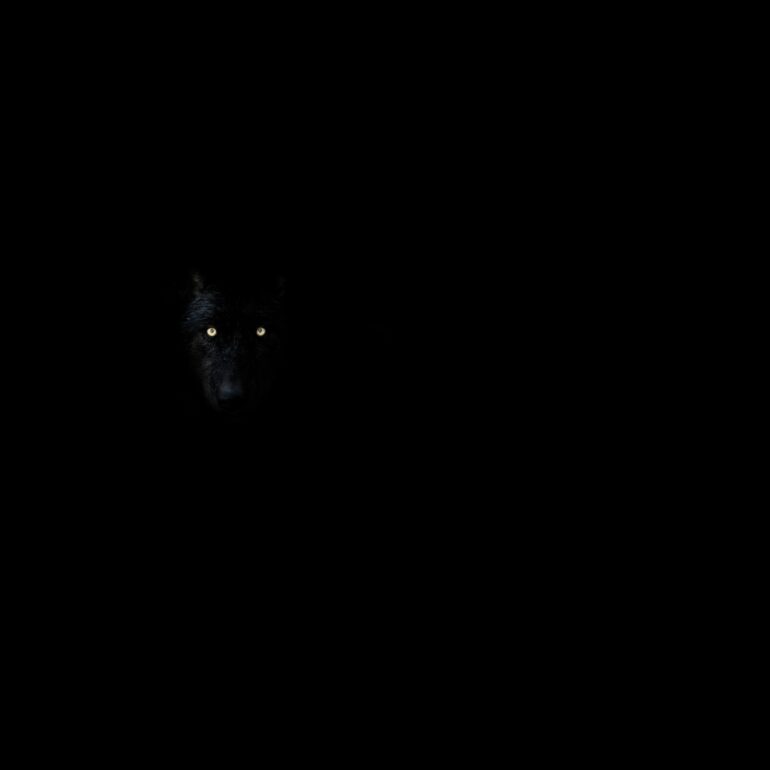

Wobbling, the red thing drifted closer, until the wolfchild stood up and waved at us. Startled, we kept quiet and still. He clambered onto the rocks, pulling his peculiar shell behind him. What was he? The last of our wolf brothers had left the island months before, ducking the waves in search of better things to eat. We would have followed them, if we could swim. This newcomer was an unfamiliar kind of animal, uneasy in his skin. It hung loose from his body as if he’d only slipped it on for a little while. And his stance was unwolflike, hands on hips, pointed ears drooping and chin thrust out in a petulant manner.

The wolfchild pointed to his chest and spoke a word. My father, eldest of our clan, tried to repeat it, but the syllables rattled like sticks in his mouth. He pointed to the wolfchild and said king, a word of welcome in our tongue. The wolfchild jumped back, shouting and jabbering. I cracked a mussel in my teeth and giggled, but Father shushed me. The wolfchild ran to the place where he’d beached his red shell and returned carrying a long, pointed stick.

Understand that when the wolfchild came, we were at peace. We had no weapons, no enemies. And so when he pointed his spear at us we were not afraid. He was our guest, and we tried to please him. We danced the stories of our ancestors, lifting our arms and raising our voices in celebration. When the wolfchild danced, he only shook his spear and stomped his feet. I watched him as best I could, but the tales his body told looked like lies to me. I wondered how he could see anything with those small, dark eyes so unlike mine, wide and yellow as the sun. He raised his spear. It was twice as long as he was high. We raised our arms, shimmied our shoulders, wiggled our claws. He hurled the spear towards the sky. It soared over our heads and we turned to watch as we would have watched an albatross in the hope she’d choose our island to make her nest. An albatross—what luck that would be! We wouldn’t take all of her eggs, only the ones we needed to live. We’d leave the rest to make more albatrosses, and then more eggs.

All of us heard the scream when the spear found its target. For a terrible moment every mother knew for certain that the cry belonged to her own child. Even now, part of me lives in that moment, hearing my daughter’s scream. But it was not my daughter screaming. All of our children were safe in the crèche. No, the child the spear found was not one of ours. A piglet, daughter of boars who roamed the highest reaches of our world. I suspect the little thing heard the commotion and came down looking for something to eat. Weren’t we all looking for something to eat in those days? I took the piglet in my arms and looked into her eyes, small and dark like the wolfchild’s but brimming with innocence and pain. The spear quivered as she gasped her last breath.

The wolfchild came running, grabbed her and held her high overhead, grinning. Everyone looked to my father, but he only led us off to bed.

We whispered on our pallets in the tall grass, watching the wolfchild out of the corners of our eyes as he paced the sand with folded arms.

He’s weak, some said. Look how small.

Others disagreed. Look at his long stick, look at his red shell. His power lies in the use of things.

He’s playing at this, I said. He’ll get hungry and tired and go back where he belongs.

We are hungry, too, Father said.

The flesh of the wolfchild was sweeter than I expected, so sweet that it wasn’t easy to set aside a share for the boars who’d lost their child. Perhaps he was younger than he looked. I still think he was only playing at being dangerous, but that was enough. Perhaps in another tale the wolfchild will go home to a warm meal and his mother’s arms. Not in this one. He’s part of our clan now, our eaten memories. Part of our stories. Part of our dance.

Houston-raised enchilada-lover Lindsey Godfrey Eccles lives in Seattle, spending as much time as she can in the mountains and occasionally practicing law. Her fiction has appeared in Ninth Letter, Hobart, Uncanny, and elsewhere. You can find her at lindseygodfreyeccles.com or @LGEccles.

Photo by Angel Luciano on Unsplash