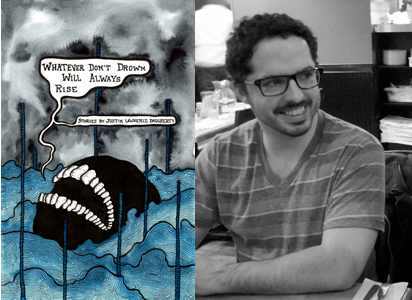

Debut novelist Justin Torres writes emotional truths, with all of the heat and hurt that they entail.

Interview by Christine Orchanian Adler

Long before he’d ever heard of the Iowa Writers’ Workshop or literary agents, before considering he could make a career out of writing, Justin Torres had written most of his first novel. “Nobody was waiting for my first book,” he laughs as he talks about the five years he had been writing without expectation. “It gave me such freedom because I was able to make it as long, or as short, as I wanted, and have a crazy ending and take as much time as I needed.” He was just writing because he loved to write.

Long before he’d ever heard of the Iowa Writers’ Workshop or literary agents, before considering he could make a career out of writing, Justin Torres had written most of his first novel. “Nobody was waiting for my first book,” he laughs as he talks about the five years he had been writing without expectation. “It gave me such freedom because I was able to make it as long, or as short, as I wanted, and have a crazy ending and take as much time as I needed.” He was just writing because he loved to write.

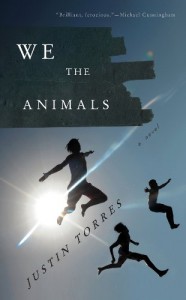

We The Animals is the story of a young man who, like Torres, grows up gay and Latino in a small, homogeneous upstate New York town. But while the incidents that happened in the book are inventions, Torres says, they are emotional experiences of the rough contours of a family very similar to his own. With a talent for using the autobiographical as a jumping-off point, Torres spins fact into fiction, draws beauty from tragedy, unearths humanity from dysfunctional relationships and packs it all into a trim, poetic debut novel. The result is an emotionally evocative book rich in language and vivid imagery. But don’t be fooled by its slender stature; its content is solid evidence that less is more, and the critics have noticed.

At 33, he is a graduate of the Iowa Writers’ Workshop, thanks to a Truman Capote Fellowship. He’s also been awarded the United States Artist Rolón Fellowship in Literature and a Wallace Stegner Fellowship at Stanford. We The Animals won the 2012 VCU Cabell First Novelist Award and, most recently, was named one of The National Book Foundation’s “5 Under 35” in Fiction for 2012. As if that weren’t enough, he was also named one of Salon’s Sexiest Men of 2011. He is currently a fellow at the Radcliffe Institute for Advanced Studies at Harvard. I tracked down Torres between his travels to talk about his book, his writing process and thoughts about his new celebrity status.

At 33, he is a graduate of the Iowa Writers’ Workshop, thanks to a Truman Capote Fellowship. He’s also been awarded the United States Artist Rolón Fellowship in Literature and a Wallace Stegner Fellowship at Stanford. We The Animals won the 2012 VCU Cabell First Novelist Award and, most recently, was named one of The National Book Foundation’s “5 Under 35” in Fiction for 2012. As if that weren’t enough, he was also named one of Salon’s Sexiest Men of 2011. He is currently a fellow at the Radcliffe Institute for Advanced Studies at Harvard. I tracked down Torres between his travels to talk about his book, his writing process and thoughts about his new celebrity status.

For those who haven’t read it yet, let’s talk about your book. Would you call it a coming-of-age-story? Or something else?

I’ve never really warmed up to the coming of age genre. I think the book falls within that category, absolutely, but when I was writing it, I was conscious of the conventional coming of age story in which there’s a slow process of coming to know yourself and identity, and I wanted to try to disrupt that. So the book is very fractured and splintered, and there’s this jump at the end that’s a little bit shocking.

There is an urgency to the book that comes through. Did you feel urgency in writing it? Can you describe the birth of the book?

As far as the immediacy and the urgency, I think there were two things. One was that I was completely broke and working dead-end jobs, and I wrote when I had time, in spurts. So there was a purity to the writing because of the urgency. I actually didn’t have that much time to sit down and write, so I would think about it all day. And then when it was writing time, I felt like I had to make it count. I had to make it all worth it. But also I was very conscious of making it immediate, getting to the meat, to the heat of the moment as soon as possible, and not having too much reflection or too much introspection because I was writing about children, and I think that children experience the world in very immediate ways. They’re very tuned in to what’s happening in the moment, and when the next moment comes, they’re ready for the next moment.

The POV in WTA is an uncommon one: first person plural. You don’t see that a lot in novels. What made you choose to use that perspective, and how do you think it helped or hurt the process for you?

I think that, as children, a really beautiful melding happens among siblings who are close in age. Your wants and desires are so much in line with each other’s—you’re literally struggling over who gets the biggest piece of pie. And all of your experiences to that point are completely similar. The family in the book is a very isolated and insulated family; they really don’t get out much. So the three brothers’ reference points are all the same. Everything that happens, happens to THEM as a collective unit, hence the ‘we’. As they age, their reference points change. They start to develop sexual identities, they start to have their own ideas and wants, and they become inaccessible to each other. To me that’s a kind of necessary tragedy, moving from that place where you feel understood and connected—as if you and your brothers are of one mind—to a place where you want really different things. You see the world in a very different way; it’s huge and it’s a very difficult kind of rupture. In this family, the narrator is queer, and that rupture is particularly difficult for him. It marks him in a way that really sets him apart and he starts to think differently about his family and his place in the family. As for the process, the first chapter of the book was something that came early, and it is entirely in the collective ‘we’ voice, and I liked it. I’m very hard on myself and what I write, and I usually don’t like anything but I really liked that and I knew I wanted it to be the opening of the book, and I knew the rest of the book had to conform to or address the first person plural.

The POV isn’t the only unusual aspect of the book. For example, it doesn’t follow the typical format of a novel. It feels more like a string of striking scenes that ultimately gel into a cohesive whole. I wondered if you outlined the story this way. Can you talk a bit about the process of creating the book?

I didn’t outline anything. I didn’t wake up one day and say, ‘I want to write a novel’ and set off. I started writing just out of the passion for the words and the sounds. Then I was like, OK, where do I go from here? I never conceived of it as a novel, but I didn’t conceive of it as a collection of stories either. It’s more like episodically linked moments. I started it out with this “we, we, we”. I also had all these snippets, so then it became, ‘what do I want to do with this, how do I want to structure the book?’ And I thought a LOT about structure. I started looking at other unconventional books that called themselves novels, for models of the different kinds of structure that were possible. I wanted it to function almost like memory. I thought about moving away from the collective identity of the brothers—the pack of brothers, with that pack mentality—and then over time having the protagonist individuate. Ultimately, that ended up being the arc of the book rather than the plot of the book. I think some people might be dissatisfied with the way in which the book pushes to the extreme of what a novel can be… but I think other people are going to be pleasantly surprised. Or I hope so.

The New York Times describes WTA as “an autobiographical first novel.” How do you differentiate memoir from fiction?

I never wanted to write a memoir. I think that this intense interest in the autobiographical elements of the book is something that is of our cultural moment. There’s a writer that I admire, Tayari Jones, and I heard her say once that people are always interested in catching a memoirist telling a lie and a fiction writer telling the truth. I don’t know quite why this is. I do know that writing fiction allows me to get at an emotional truth. The incidents that happened in the book are inventions, but they’re true emotional experiences. To return to those emotions, I wanted to get in, get to the heat and get to the moment and then get out again.

Which writers have been the biggest influence on you as a writer and why?

I admire Grace Paley, her language and rhythm, and how much happens to the characters in so little space. The Lover by Marguerite Duras was great because it taught me that you can keep all that ‘white space’ and all those silences in between. Stuart Dybek is amazing, as precise and concise as I can ever hope to be. Jim Grimsley tells all the ugly truth. I read poetry; I love the way poems marry a complex truth about human nature to a specific image in a very small space. I want to do that in my own writing. All along the way I’m always reducing, reducing, reducing.

How has being Latino had an influence on your writing life and community?

The book certainly addresses the biracial, bicultural experience, an experience that is more and more common for Latinos of my generation. And it seems to me that the book has really been embraced by Latino readers. I think queer readers, working class readers, and Latino readers are all finding the book through word of mouth. All of these various identities are ones I proudly wear on my sleeve.

What’s the best advice you’ve ever received as a writer?

I was in a workshop with Dorothy Allison (author of Bastard Out of Carolina) and I had written something which was very angry and raw and real and honest in its anger. And she responded well to it, but she said, ‘anger is a great motivation and will get your butt in the chair to write. But you have to get the grace and the beauty in there too. Otherwise it’s worthless; it’s a rant, the settling of a score.’ I really took that to heart.

What’s the most important piece of advice you can give to aspiring writers?

I hate giving advice; I hate speaking in the second person. So I’ll say some first person statements. I started writing not out of any desire to be published. The reason I started writing is the same reason that keeps me writing: because I love the look of the words on the page, the sound of the words read aloud, the rhythm and the lull. And I fail all the time, but I love the feeling when I get it right.

We The Animals was published by Houghton Mifflin Harcourt as the first book of a two-book deal.

Christine Orchanian Adler is a writer and editor whose articles, essays and book reviews have appeared in various publications throughout the Northeastern United States and Canada. Her poetry has appeared in Inkwell, Coal: A Poetry Anthology, Penumbra, Tipton Poetry Journal, and online at Bird and Moon, Damselfly Press, The Furnace Review, Literary Mama and elsewhere. She blogs at feedalltheanimals.blogspot.com, and is currently at work on a novel. She lives in New York with her husband and two sons.