Soren A. Gauger

This week we’re very excited to present three fiction pieces from Canadian writer Soren A. Gauger. Read Wednesday’s story here, and Friday’s here.

On Saturday I took a stroll with my wife, in the park we both adore for its white blossoms and occasional squirrels. The sun was bright without being sentimental, we bought vanilla ice cream. It was a thoroughly charming scene. But before long I gleaned that with every bite of the ice cream my wife’s face was twisting into a grimace, or perhaps a scowl.

Ice cream too cold? I ventured.

Your neck, she said, manufacturing the same sour look, what on earth is that? I groped at my neck, and indeed: my fingers struck something knobby and misshapen. The skin was coarse where once it hadn’t been, and the flesh wiggled about, just as though a solid, spherical bone had formed beneath the skin.

Alarmed, I made for the washrooms. They were just behind an open-air shooting gallery and the periodic impacts made the mirrors vibrate and rattle. I waited for a fat man to clean the bubble gum from his son’s hair, and then approached the mirror myself to have a closer inspection of my neck.

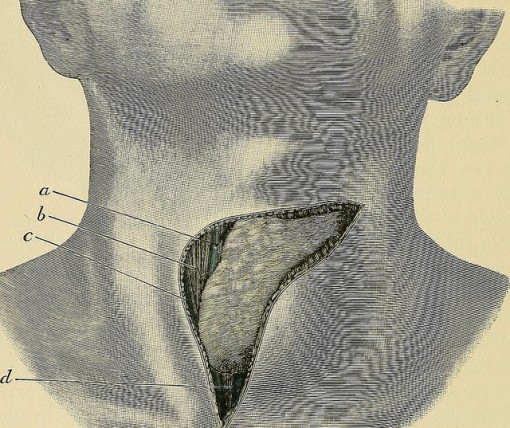

Things were worse than I had anticipated. The growth resembled nothing so much as a stunted, pink finger protruding a few inches below my left ear. The shooting abruptly ceased, the hum of the fluorescent lights became audible, and things became eerily still, I should almost say portentous, there in the bathroom. Then there was a scream from somewhere beyond the mirror, and the shooting and rattling resumed. I walked outside feeling disconcerted, but still determined to enjoy the day.

Although my wife did my best to conceal her curiosity, she could not keep herself from staring at my neck for the rest of our walk, on her face was written a mixture of revulsion and concern. This made me touchy and irritable, not least because I myself could not forget the revolting bump. All our attempts at other conversation were in vain. Behind our suddenly bland observations on the birds, the children digging in the sandbox, or the inordinate number of dogs, there crouched the ugly fact of the new growth on my neck. Eventually, and quite out of the blue, my wife said: I’m quite sure it’s just an insect bite. It’ll be gone in a day or two. And then she nodded her head firmly, as though it was decided.

The days were warm and balmy. This made wearing turtlenecks a constant source of discomfort, but I kept it up, for the sake of my dignity. I did my best to go about my daily affairs and to forget about the bump, as though by simply neglecting it I could negate its formal existence. But after four days it became painfully apparent that, far from shrinking, the demonic thing was actually growing. During meals, which had become awkwardly silent, I would chuckle to myself sometimes and say: It’s just so senseless, so goddamned senseless. Eventually my wife placed her hand on mine. It’s high time we just forgot about it, I think, she said with a sympathetic smile.

I made an appointment to see Doctor Kent. Doctor Kent was a model specimen, with ululating muscles, wiry hair, and shimmering-white teeth. Like with all doctors, his welcoming smile looked like the prelude to a calamity. I peeled back the neck of my turtleneck shirt to give him a peek and for just a second I saw him shudder in surprise.

Hey, look there! he said.

He prodded at my neck with a metal wand, then he clucked his tongue.

Come back Tuesday, he said. I need to look into this.

On the way home, I stopped off at a bookstore. I located a title on the popular medicine shelf entitled Deformities of the Face and the Neck. Being rather uncomfortable about my purchase, I took a few other titles off the shelf (Uncovering Hitler’s Final Solution and The Holocaust in Colorized Pictures) at random, to distract attention. Nonetheless, standing there in front of the young man at the counter I started feeling defensive. I don’t have any facial deformations myself, I said nonchalantly, or of the neck. He grunted and nodded. But it’s a terrible thing, I imagine, I continued unnecessarily, and you have got to prepare yourself for the worst before it sneaks up and catches you off guard. He gave me one of those slack-jawed expressions so typical of young people nowadays, especially when you are trying to communicate something important.

When I arrived home I stuffed the medical books under my jacket and entered the house with the remaining two titles under my arm. My wife gave me a kiss, and then took the books from me to see what they were. She scanned the covers—a platoon of goose-stepping soldiers under a swastika-sun on one, a ragtag pile of emaciated corpses on the other—and then her eyes traveled up to my face, and fixed there questioningly.

My wife went to the kitchen to prepare supper and I closed myself in our bedroom, drew the blinds, and began flipping through Deformities of the Face and the Neck. Before my wondering eyes unfolded such horrors as I had never dreamed were upon this earth. Men’s faces turned to boiled wax and dripped off their bones; swellings, odd concavities, hard protrusions; there were blotchy discolorations that flowered on the forehead and dribbled down the neck and below, as demonstrated by a bare-chested, poker-faced victim; a disorder that caused the left-hand side of the face to grow to twice the side of the right; something called the Bulgarian Neck, which made all the veins in the neck become as thick as cords and distended; dysgorgia, facial epilepsy, withering lymph nodes; pages and pages of speckled rashes . . . I heard the click of the bedroom door and hastily sat on the book, at the same time throwing open The Holocaust in Colorized Pictures and adopting a posture that suggested I was lazily perusing a photograph of three hanged men.

My wife wanted to know if I preferred cauliflower or carrots with dinner. I could tell from her face that she suspected some kind of clandestine activity was afoot in the bedroom. But she left me in peace, and I went back to the book.

I could find no reference to my lump.

Over dinner, in the middle of one of our long silences, my wife suddenly said: I do wish you would stop wearing those turtlenecks. It’s so much worse not being able to see it and yet knowing for certain that it’s there.

Soren A. Gauger is a Canadian writer and translator who has lived for over a decade in Krakow, Poland. He has published two books of short fiction, Hymns to Millionaires (Twisted Spoon Press) and Quatre Regards sur l’Enfant Jesus (Ravenna Press), and translations of Polish writers, Jerzy Ficowski, Bruno Jasienski and Wojciech Jagielski. His essays, stories, poems, and translations have appeared in journals in Europe and North America, including the Chicago Review, The Southern Review, Capilano Review, Contrary, Asymptote, Cossack, American Book Review, and Words Without Borders. His first novel, Neither/Nor, will be published in October in Polish by Ha!Art Publishers.