Justin Lawrence Daugherty is a migrant living currently in Omaha, Nebraska. He is the managing/founding editor of Sundog Lit. he is at work on a novella about Aurelio the Lizard-Boy: Now the Destruction of Days.

If I jump in, he says, will you tell me more about the chuppa, but I know he means his dad, about the track marks on his arms, about the empty cupboards, about yellow fingernails, dried up rivers, broken bones. He wants to know about all the horses that haven’t starved, about trees that have lived for hundreds of years, about animals blind without eyes in the darkest places in the earth, about how we try to kill ourselves over and over but what we really want is the rushing heartbeat of near-death, the pumping, the blood.

Monkeybicycle: The prose in Whatever Don’t Drown Will Always Rise is phenomenal. Rich, evocative, visceral, powerful. It’s blurbed by Robert Kloss, who wrote one of my favorite books of all time, and I feel there’s a similarity between the two of you in reading these ten stories. Tell me about language. What you’re drawn to, how you use it.

Justin Lawrence Daugherty: First, thank you for the kind words. Kloss is a huge influence on my recent work – as you noted rightly. I first stumbled upon him in SmokeLong last year and instantly was so excited for The Alligators of Abraham. Language, for me – like the stories and actions and movement – ought to always be at risk of erosion or implosion. There are quiet things and everyday things, but I (hope) I don’t write those things. I’m interested mostly in language that is always on the verge of breakdown. I think I’m most drawn to reading characters always close to destruction, and that’s what interests me in writing, too. I want every sentence to carry weight, to be able to blast ahead with a train’s momentum. It’s important to me that the language reflects the mental state of the characters and the turmoil of the world around them. That momentum is hard to maintain, sometimes, and it can be exhausting to write, but I never want to write a sentence that lacks motion. A good friend of mine always talks about not being able to read anything that isn’t life or death – and, I try to write for readers like him. There are excellent writers who masterfully convey the desperation in the quotidian, but I just don’t think it’s in me. So, there’s this idea of life or death struggle in every story, but I hope that carries over into every word and sentence as well.

I think about a story like “Roadmap” in terms of exactly what I want my work to accomplish. That story came out of a science report I’d read about the universe actually being almost done creating stars – which felt like an incredibly saddening yet beautiful thing. The universe is on its way out. So are we. That’s what I’m drawn to in my writing. This sort of coming extinction.

Mb: Joyce wanted to make the commonplace epic but highlighted this in a structural way and with an intense focus on minutiae. These stories, while not necessarily commonplace are full of people doing relatively normal things, but in describing these actions they expand with such visceral enormity that going fishing sounds like life or death. Was this intentional, turning the normal into the epic?

JLD: While I write with this idea in mind that everything is tending toward ending, I’m also conscious that lives are not always spent with every action being monumental. We eat. We fish. We have sex. Characters have to do things. So, too, do my characters. They have to seem like us. So, there’s that – but, there’s also this need in me to write this extinction into my work. So, in trying to make my characters human while also writing down desolation, there definitely is an intention to turn everyday action into epic, in a way. Most of my work since the work that appears in this book is even more intensely focused on epic, shattering actions. I think I’m just drawn to epics, in general, stories that convey – no matter the subject – an air of immensity.

Mb: While the prose is consistently powerful, each narrator manages to be singular and different from every other narrator in the collection. The attention to cadence and diction is probably what most impressed me about Whatever Don’t Drown Will Always Rise. How important is originality in voice?

JLD: Originality in voice is so important. I get bored easily. I read a first sentence that may have a similar voice to something else I’ve written and get frustrated. I quit stories easily. I want each of my characters and narrators to feel real. If I forget about originality in voice, they of course become sort of archetypes within my own writing, and that’s dangerous, at least for me. Also, I try to write away from my own voice, from having my work echo me. I’m there, of course, but I want the voice of the story to be a life of its own, to breathe independently of me.

She sip her drink, she downed it. “Let’s go somewhere far away,” she say. She stroked the inside of my leg, a vibration. “Or maybe let’s just go to your place and I tell you all the things I know?”

Mb: There is a very brooding, almost menacing atmosphere hanging over these stories. Where does that come from?

JLD: I don’t write calmness well. I mentioned this obsession – and it is an obsession – with extinction and ending, with life or death. In a way, I think we exhibit the greatest will to live and survive in our greatest moments of desperation, when we’re most at risk of implosion. So, I’m interested in writing that lives in the fringes, where chaos is always imminent. Because that’s the universe we inhabit.

I’ve always been most interested in that atmosphere in my reading and in the movies and television I watch. Cormac McCarthy, Deadwood, Breaking Bad, The Wire. Amber Sparks, Lindsay Hunter, xTx, Delaney Nolan. I’m most interested in consuming that sort of material, so that’s what I write, too. I’m most interested in the storm and what comes after.

Mb: These ten stories are all quite short. I think there’s a growing tendency since literature went online to shortening stories, with most journals not even considering stories longer than 5,000 words. And you yourself are an editor of an online journal. Do you think that affects your writing? Do you think that’s changed who we are as writers since literature’s gone online?

JLD: You know, for most of graduate school, I was writing these long, boring stories that took forever to get somewhere. I only started writing really short work in late 2011, about halfway through my final year. I was just bored with my work and wanted to do something different. And, it clicked, somehow. But, also, I think I was influenced by that shortening trend. Everything I was reading was very short and most everything online was short, so there was a natural tendency to seek brevity. I think if what we’re reading is mostly very short, we’ll be influenced to write shorter work. If I tried to write a novel right now, I’d have to drastically shift what I’m reading.

Editing definitely affects my writing. I prefer brevity over something that’s pages too long without necessity. As I write, that’s definitely on my mind – especially since I began Sundog Lit. I’m conscious of the need for a certain container for a story. I start at the very short and see if it’s small enough in scope to be a short piece. Very rarely anymore am I writing anything that needs to be a longer story. Even the lizard-boy novella I’m working on is composed of flash pieces, and I think that’s where it’s failing as a whole right now: there are many pieces that are not working together as an epic, yet, and there’s where it needs to head. I have a backlog of novel ideas that are haunting me, but I don’t think I’m ready quite yet. The very-short story is still a great love.

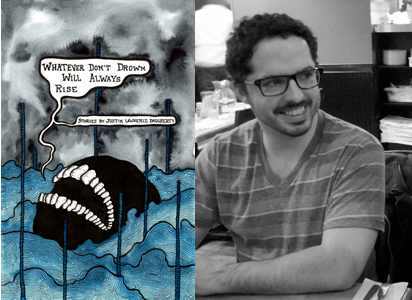

Purchase a copy of Whatever Don’t Drown Will Always Rise here, & read more from / about Justin Lawrence Daughertyhere.

Edward J. Rathke is the author of several books, one of them published [Ash Cinema, KUBOA Press 2012], two more coming out soon, as well as various short stories online and in print. He writes criticism and cultural essays for Manarchy Magazine and regularly contributes to The Lit Pub where he also edits. More of his life and words may be found at edwardjrathke.com.