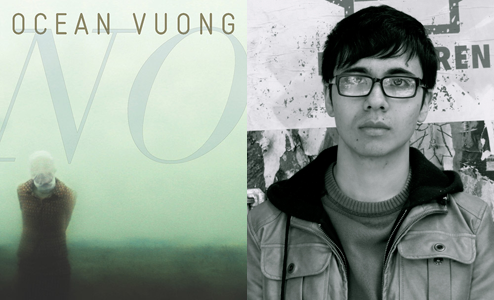

Born in Saigon, Vietnam, Ocean Vuong is a recipient of a 2014 Pushcart Prize. Other honors include fellowships from Kundiman, Poets House, and the Saltonstall Foundation for the Arts, as well as an Academy of American Poets Prize. Poems appear in Beloit Poetry Journal, Crab Orchard Review, Quarterly West, Denver Quarterly, Guernica, The Normal School and the American Poetry Review, which awarded him the 2012 Stanley Kunitz Prize. He lives in various boroughs throughout New York City.

Monkeybicycle: No is an absolutely gorgeous collection of poetry. It’s haunting and reminds me of lives I haven’t yet lived. It’s also dated from 1988 to 2006. What’s the significance of placing a timeline for it?

Ocean Vuong: Those dates mark the life of a dear friend of mine whose untimely passing from suicide is the emphasis of this book.

Suppose you woke

& found your shadow replaced

by a black wolf. The boy, beautiful& gone. So you take the knife to the wall

instead. You carve & carve.

Mb: No plays with form and the shape of a poem quite often. How important is the form and how does that influence the content and sound?

OV: Besides being a vehicle for the poem’s movement, I see form as an also an extension of the poem’s content, a space where tensions can be investigated even further. The way the poem moves through space, its enjambment or end-stopped line breaks, its utterances and stutters, all work in tangent with the poem’s conceit. In this way, form is very important to me—but also very challenging. All of a sudden a single path diverges into hundreds. With so many choices it’s hard to know exactly which composition serves the poem best. I think the strongest poems allow themselves to collapse completely before even suggesting resurrection or closure, and a manipulation of form can add another dimension to that collapse.

Hope is a feathered thing

that dies

in the Lord’s mouth

Or so the story goes. Every boywith a broken heart wants to feel

the earth pull him

into its arms

Mb: “and then the blizzard” might be my favorite poem I’ve read all year. It’s full of sorrow and beauty and longing, something like love. Can you talk about this poem specifically?

OV: This poem, like many of the poems in this book, actually began much earlier— before I decided writing was a practice I would pursue seriously. After my friend’s death, I started writing these strange letters to him—to the dead. Some nights all I could do was fill page after page of yellow notebook paper with “I’m sorry I’m sorry I’m sorry I’m sorry…” Other nights I managed to write down complete sentences. Some of the poems in No were written with language lifted from those letters. I feel awkward turning such personal material into poems—but the task also felt important at the same time.

I was also thinking of Van Gogh during the writing of these pieces: how, towards the end of his life, he abandoned the brush all together and worked with the tubes of paint themselves—scraping them onto the canvas and leaving an exact presence of his life through a visceral evidence of composition. I found this to be a startling and affective preservation of emotion that transcended the boundaries of language and rationale. I tried to translate this notion in the book by disrupting optical realism, often abandoning subordinate clauses or letting sentences bleed into others—sometimes contradicting syntax and contexts. In this way, I hope the poems exist more as enactments of grief rather than presentations of it.

Mb: How has being an editor changed your poetry? What kind of lessons have you learnt from being on the other side of the submission process?

OV: I enjoy very much my work as an editor—although I’m a bit embarrassed to even call myself that. I am more of a glorified acquisitions reader at Thrush Press. I read chapbook submissions and then champion the ones I love to the rest of my team and, if all goes well, a little book surfaces a few months down the road. I’m just happy to be a small part of bringing good poems into the world. And I know how important it is to the poets—to have their own books: the fruits of tireless labor. I know how hard writers work just to get very close. In short, it makes me happy to see other poets happy.

Mb: You’ve received a lot of positive attention and accolades for your poetry—all very well deserved. But how has it effected the way you see your own writing? Has it changed the way or reasons you write?

OV: The recognition has been pleasant and, indeed, encouraging—especially for an emerging poet like myself. I am very grateful as it has given me a lot of needed confidence in my development and growth. But as jubilant as I am for the acknowledgement, I am just as eager to turn back towards the inner self—where all the poems begin in the first place. It’s easy to get caught up in awards and accolades but I think there is just too much at stake—too many questions and explorations to undertake and the poem is the perfect space for those investigations. I feel like my writing changing all the time—from one poem to another. Nothing is in stasis. And that’s the excitement, isn’t it? There are so few limits to a fresh page—if at all. It has no idea who I am or what’s on my CV. I arrive at a blank sheet of paper as an exile lands on a new planet. Alien, I have to prove myself all over again. I have to learn all the new gods—and how to please them. I can’t turn back.

Read more from / about Ocean Vuong here. Buy a copy of No here.

Edward J. Rathke is the author of several books, one of them published [Ash Cinema, KUBOA Press 2012], two more coming out soon, as well as various short stories online and in print. He writes criticism and cultural essays for Manarchy Magazine and regularly contributes to The Lit Pub where he also edits. More of his life and words may be found at edwardjrathke.com.