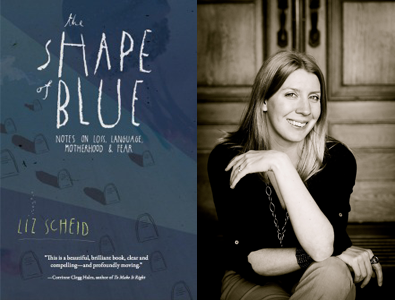

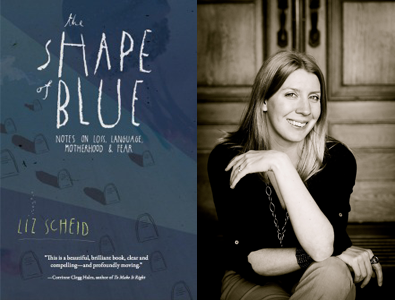

Liz Scheid received her MFA (poetry) from California State University, Fresno in 2008. Her first book, The Shape of Blue, won The Lit Pub’s first annual prose contest and is out now. Her essays and poems have appeared in many literary magazines, including: Mississippi Review, Third Coast, Sou’Wester, The Journal, Terrain, Post Road, The Collagist and others.

Monkeybicycle: The Shape of Blue is beautiful and heartbreaking. How does art help us grieve? What can we learn from loss?

Liz Scheid: It allows us to bust through the surface of stuff, and explore what’s inside. Imagination is a tool to do this. It helps us get in touch with all of our monsters so to speak, the things we hide or don’t want to see.

I think from loss, we can learn to see things differently. I don’t, by any means, consider myself an expert on the subject, but I do think we learn to see ourselves and others differently. During grief, you dip down so low, and come back up, and go back down, so each time you go up or down you see something you hadn’t seen before or you see it in another light or shape.

It was Nicholas Copernicus, inventor of the solar system, who declared the sun the center, surrounded by six planets: Mercury, Venus, Earth (with moon), Mars, Jupiter, Saturn. As centuries piled on, the system grew more complex. Uranus was seen through a telescope in 1781, even though it had been spotted at least six times before but mistaken as a star because of its slow movement. I was fascinated with their minds and obsession for answers. One of the exhibits displayed replicas of Galileo’s telescope made of wood and leather. It wasn’t the first telescope, but his version enhanced observing power to eight-times magnification. With the invention of the telescope, planets were popping up everywhere: Ceres, Astraea, Flora, Hygeia, Kalliope. And in 1846, Neptune emerged: a beautiful blue balloon. By 1854, there were 41 planets! But the planets were supposed to be ethereal, distinct. It seemed fair that the biggest survived as planets. After all, people might get overwhelmed. Too many planets meant too many distinctions. How could they possibly remember so much? The smaller ones were to slip into minor categories/subtypes/subsections, below the norm, below the surface. Almost, but not quite. See also the subconscious. The planet criterion was still broad, blurry, and when Pluto surfaced, it pushed boundaries. . . .

Mb: The essays within The Shape of Blue tend to be a combination of disparate components. I love the little details included about the Haldron Collider and so on. How do these little details, seemingly so disconnected from the rest of your essays, help contextualize your experiences?

LS: I’m always interested in the gaps. I want to know what happens in these spaces, the spaces where language largely seems to separate us. In particular, many of these details were from scientific articles I had been reading, and had immersed in the language, and how after reading these articles and facts, I saw so many patterns and connections between them and human experiences, in my experiences, etc. The gaps began to collapse a bit.

During grief, it’s hard to find the language to describe your thoughts and emotions. It’s hard to even understand what it is you’re feeling, as well. So we find other ways to get in touch with ourselves by using the imagination.

My dad had the same dream several nights in a row: he’s fishing, everything begins to ascend into the air—silver fish, shadows of other fishermen, snakes—and as he begins to rise in his boat, he stops midway. Everything else rises past him as his boat hovers halfway up into the sky. When he tells me about this dream, I listen closely because usually he keeps his feelings and emotions to himself.

Amaya tells me she dreamed about yellow hummingbirds. Everywhere. She was so small, she could ride them.

During pregnancy, I dream a lot about my sister. At some point in every dream, I realize it isn’t real, that I’m dreaming, that she’s dead, and I ask her what she’s doing here. She never answers, and then I wake up and everything feels distorted again. Like she keeps dying over and over.

Mb: There’s a great attention to language within The Shape of Blue. How do you think the language of loss effects how we process it?

LS: I’m in love with language, with words. I think it allows us to bend our brains and travel so far. In other words, you can get lost in beautiful language in the sense that you’re letting your mind wander into different spaces. It’s also a tool to get past the surface and get inside the subconscious and explore all that dark and horrible and ugly and violent stuff. All the stuff that’s hiding in the shadows.

Mb: You have an MFA in poetry. How do your experiences as a poet feed into these essays? Or how did they prepare you to write them?

LS: Once you study poetry, you can’t ever really go back. This is how I see the world, how I approach language and wonder and really everything for that matter. In other words, it would be impossible for me to turn off the poet inside.

Mb: You won the first Lit Pub contest and are now seeing your essays come out as a book. How did it feel winning the contest, and how does it feel finally seeing the book released?

LS: It’s incredibly surreal still to me. I’m amazed and astonished and terrified (I don’t know why, but am) and overjoyed. When the Fed Ex truck pulled up last week, I was backing out of my driveway and almost backed right into his truck. I had been waiting for that moment for days, and here he was, finally here, bringing my books. I flew out of my car and almost attacked the driver. He said, “Must be something good inside?” He probably thought it was drugs or something. He looked pretty startled. I ran inside with the box and my three-year-old son trailing beside me. He kept asking me, “what is it, Mommy? Is it candy?” I said, “yes. Sort of.” At that moment, I froze for a few seconds before I opened the box. I had to take a few deep breaths. And even when I opened it and saw a flood of blue books inside, it still felt unreal.

Read more from / about Liz Scheid here. Buy a copy of The Shape of Blue here.

Edward J. Rathke is the author of several books, one of them published [Ash Cinema, KUBOA Press 2012], two more coming out soon, as well as various short stories online and in print. He writes criticism and cultural essays for Manarchy Magazine and regularly contributes to The Lit Pub where he also edits. More of his life and words may be found at edwardjrathke.com.