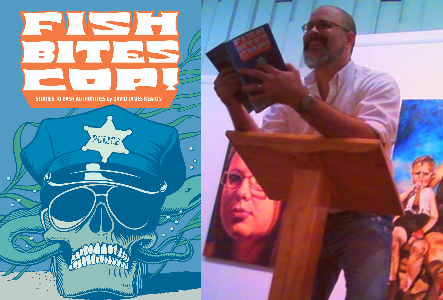

Tim Horvath is the author of Understories (Bellevue Literary Press) and Circulation (sunnyoutside). His stories have appeared in journals such as Conjunctions, Fiction, The Normal School, and elsewhere. His story “The Understory” was selected by Bill Henderson, founder and president of the Pushcart Press, as the winner of the Raymond Carver Short Story Award. He teaches creative writing in the BFA and low-residency MFA programs at the New Hampshire Institute of Art, and has previously worked as a counselor in a psychiatric hospital, primarily with adolescents and children and young adults with autism. He received his MFA from the University of New Hampshire, where he won the Thomas Williams Prize. He is the recipient of a Yaddo Fellowship, occasionally blogs for BIG OTHER, and is an assistant prose editor for Camera Obscura.

When we were awash with youth, we were all led to believe that our father was assembling a booko called The Atlas of the Voyages of Things, or, as we shortened it, The Atlas. That it was eventually destined to enter the world was incontestable–one day, assuredly, we would march into the bookshop behind his gallant stride, and there, on the shelf, would sit the book, sprawling, coffee table—ready, his name beaming from the front as on a theater marque. “You see, boys?” he’d say, and we would solemnly nod.

Monkeybicycle: The more literature turns to the internet, I’ve found that it’s become standard for stories to become shorter and shorter. Even most of the short story collections I come across tend to be full of stories under three pages long. Understories, however, is filled with longer stories. How do you think the internet has changed the way we write? What do longer stories and novellas give us that flash fiction doesn’t?

Tim Horvath: Let me begin by saying that I love flash fiction—I’ve taught classes in it and been bowled over by much of what my students turn in. To me, flash fiction is prose poetry—I’m too lazy or plot buried too many feet down in my list of priorities to be able to name the distinction, though I’m glad to hear it from anyone who can explain it. It’s been floated that I have a novelist’s disposition—that’s what my advisor, Alex Parsons told me in grad school, where most of my stories were pushing 10,000 words, and there was always a “toymaker moment,” named for the moment in one of my early stories where the whole thing takes an 87 degree turn and the characters all beeline it to a toymaker’s house. This was before I knew anything about anything as far as word counts and limits and that kind of thing—it just felt like the work was easing into its natural dimensions. I’m glad for the existence of both, though. Some days, often in the morning, oddly enough, I’ll feel this hankering to devour flash fiction, something complete and savory—it’s like when you wake up really hungry or something. Other times, nothing could feel less satisfying. My reading is very mood-dependent, and I guess I have a lot of moods, even though I think I play it pretty even-keeled on the outside. Sometimes I want a quick shower, sometimes a drawn-out bath, and sometimes the life aquatic.

It’s tough to generalize about the role of the Internet in writing. It’s always there, isn’t it?—this pulsating thing. It’s like suddenly there’s this second sun in the sky. Sometimes we can forget about it, and sometimes it leaves scorch marks on our shoulders, but either way it’s there. Of course it’s changed the way I read—I find tons of stories by following random links online and printing them out (yes, I still do print them if I hope to get anything out of them).

I think longer stories allow us to change as we read them, to grow along with them and into them, in a way that flash generally doesn’t for me. Flash meets the me that I am and we fist-bump or embrace or run through Marx Brothers antics with one another and it’s over. Whereas in a longer work, I find that an initial burst of infatuation and enthusiasm can be deceptive, and yet I can settle in for the longer haul, something more vexed and complex, a push-pull. And, too, I can wait for the work’s (apparent) flaws to reveal their inner shape and chemistry and raison d’etre, and come to find them compelling and, occasionally, irresistible. For “flaws” you can easily substitute “characters” and “take on what it means to be alive.”

Mb: I think the internet allowed for the internet lit community to develop and thrive, but I often feel as if it’s a community constantly and exclusively in conversation with itself. How do you feel about the indie lit community and how has it changed publishing?

TH: I think it’s still reshaping publishing in ways subtle and overt. I feel as though something has happened in the past few years which is particularly exciting, in that the hierarchies feel like they’re collapsing, or maybe bending, folding in some kind of origami-like way—there are still aesthetic hierarchies, but whatever the new ones are, there is a wider range out there. I don’t think you can walk through the AWP Book Fair (after you’ve popped your fistful of anti-vertigo pills) and not recognize that. I don’t think there is so much an internet lit community as there is a lit community which relies on the internet as a primary way of augmenting its production and its celebration of art and life and the blurry lines in between. Roxane Gay and Matt Bell and Gabriel Blackwell and Kyle Minor and Amber Sparks are authors of extremely various sensibilities, though I admire one and all. I’ve met them all through the Internet, and who knows if I would’ve otherwise? Probably there is always a sense in every generation that serious artists are in conversation with one another and their forebears more than with the general population, at least in countries that aren’t living under severe, unsubtle political oppression, and always, of course, with a few exceptions in the form of breakthrough writers who are also public intellectuals. My sense is that the conversation will widen and broaden over time. When I see how empowering writing is to younger students—that it offers them something that no video game, no Youtube video, no meme, no chat, can, or rather that it can incorporate much of what they are getting from those other things but reshape and remake it as something more reflective, more penetrating, more volitional and meaningful—then I can only imagine that the largely free, increasingly inclusive, playful and impassioned writing community will be a destination for more and more younger writers.

I’d like to say that I can balance my online life and my off-, but the truth is that I’ve yet to find that equilibrium. I’m typing this right now on my 1990s era Fuijitsu 700-series Lifebook, which requires several pack animals in order to comply with OSHA and PETA guidelines. Seriously, this thing is old school, but part of what I love about it is that it lures me away from the Internet—it is essentially a typewriter which happens to run Microsoft Word, or the closest I can get to that configuration. Surely the Internet has changed the way my brain works, not entirely for the better. Different parts of our brains are activated by different actions, I take it—the choreography of our neural pathways is shaped by how we dance, so to speak. In many of the writers I grew up loving (I say “grew up” meaning in my 20s and 30s, which is when I’d say I came of age as a reader), there’s a brute physicality to their work. I’m talking Vollmann, Annie Proulx, Denis Johnson, Rick Bass, Junot Diaz, Anthony Doerr, Jhumpa Lahiri, DeLillo…and through this physicality a constant impingement of the world beyond the virtual one, a world of bodies and their triumphs and failures—poison, food, ice, skin. I worry about what happens to literature in its ability to speak to the non-virtual world if we spend our lives in front of computers. I know writers have always done this—sat or stood at their typewriters, but they were putting the world into their blank pages. Now it can feel as though one has the world already at one’s own fingertips, coming at one, or lurking just beyond in a mirage of continual peripheralness, continual just-beyondness. It’s not wholly a mirage, though, that’s the thing. Anyway, this isn’t necessarily a bad element to have in one’s writing—that is, a pursuit among others—we don’t always have to be seafaring beings subject to actual seasickness and contending with fleshly whales and with the indifference of the horizon. I don’t think it’s just the Internet—it’s contemporary post-industrial society that equates the physical with the menial, labor with laboriousness. We have to invent excuses and force ourselves to work out, to lift and to move and to do what our bodies do naturally. It probably goes back farther than that—the Buddhists have been encouraging us to devote another sort of attention to mind and matter alike since time immemorial. Myself, I teach a class called The Senses in part because enriching their stories with sensory details makes my students better, more invigorating writers, but also because I want to bring blood into my own extremities, coax feeling back into those aspects of being alive that tend to atrophy if we become walking screen-savers or cogs or zombies or whatever your metaphor of choice is for that which renders us only semi-aware and awake.

So all of this—this tangled relationship with the Internet itself, inflects my feelings about the independent writing community, which on the whole is one of the coolest, most welcoming, funniest, smartest communities I could hope to be a part of. I try to tell my students this—You are already part of the literary community!—it’s not gated, and you don’t have to apply to get in. It probably was always sort of this way, but I think it always felt like there were fewer gates and maybe they were more intimidating to get past. Nowadays, it’s more of a BYOG—bring your own gate—kind of affair. All you need to do is read, write, have passion and a sense of humor, and it helps if you love words and playing with them. Words with Friends.

As for who this community speaks to, I’m sure there are corners of the Internet that are mere echo chambers, but I think you’ll find others which are speaking beyond that. The only problem is finding out about them. I’m constantly reminded about how little poetry I read and how much great poetry is out there any time I happen to take the time to pause and actually read some poetry. Most of the time I’ll think, “How the hell have I never heard of this person?” and moreover, “How disturbing I might not have ever heard of this person/read this poem if I hadn’t followed this ridiculously unlikely sequence of finger-mouse compressions and wound up here?” I suppose unlikeliness is stitched into the very fabric of the world—Daniel Dennett uses Borges’s Library of Babel to show this in Darwin’s Dangerous Idea, how very long the odds are of life coming to be in the universe, for instance, much less the life we like to call, in spite of the numerous exceptions, intelligent.

In any case, the conversation is surely opening up, gradually. So many people got exposed to Matt Bell’s novel, for instance, and what a good thing that is, considering how challenging and uncompromising it is. That so many are grappling with it is in itself not negligible. Goodreads is an instance of a really vibrant, highly literate, funny and self-aware community. Some of the feistiest, most creative book reviewers (yes, it is a creative form unto itself, not merely an analytical response to creative work, as they prove) are thriving on Goodreads. There’s been some controversy of late as Goodreads cracked down on the content of certain reviews, but the core community appears to have weathered that and remains strong.

And another: Not infrequently, shadows do flirt with color, this being one. Because of how the moon moves through Earth’s shadow, coupled with the light-filtering effects of Earth’s atmosphere, the moon appears bloodred as Mars. The cold metal of my car’s hood yields a bit as I lie back. I want to shout through the neighborhood, pound on doors–rouse the mesmerized viewers of Lost (are they any less lost than the characters on the show?) and the compulsive checkers of email. I want to share it with someone, but the street is silent. Others, out there beyond my block, must be watching this, too, but I can’t think of anyone. For a moment I consider calling one of my former students–there are over a thousand, with one or two who stand apart, who might pick up warmly, wish to talk about things other than the eclipse, inquire how I am and ask after Saskia. I might take poetic license, borrowing the stories of some of my more illustrious colleagues about consulting with the designers of the game Goad (“gonna make Halo look like Ms Pac-Man”), about extra-tight security clearance while decoding maps, sifting for the anomalies whose discovery could forestall disaster. Something about this incarnation of the moon makes the truth feel malleable, as if it can be suspended without altering its fundamental features. But then, I think, why not just be blunt–the department’s on the brink of oblivion, and a tinge of black mold sits on my shoes from earlier in the week. I glance at it; in this earth-fed moonlight, it is nearly impossible to resist finding a pattern there, something that belongs and will persist long after I slip them off and head upstairs.

Mb: Every single story is wrapped around such an intensely interesting but also peculiar idea. They feel as if the narrator is stuck in a maze digging deep into a mystery to find a way out. How important is the structure of a story?

TH: The stories all start from different places—“Circulation” began with the invocation of this library book dust jacket from which key words, the actual substance and references, had been omitted, and from there it was a question of figuring out why. And it turned out to be about two books, one imaginary and epic, sprawling, the other real and slim and forgotten. Some of the stories began with premises. At least one began with a prompt, a quote from a book. A couple of them emerged as I was attempting to do exercises that I’d assigned to classes. And one, “Runaroundandscreamalot!” began with the title, which in turn set the stage for a certain mood, an energy that would propel the dynamics of the story. The challenge was to write a story manic enough to earn out the advance of that outrageous title, but also to have characters who could stand in the midst of mania and juvenileness and have you somehow care about them.

I say all this as a corrective to the notion that all of my stories begin with an idea, which is almost the opposite of the reality, and to emphasize that there are a lot of ways in. Having said that, though, I love the image of mazes and narrators stuck in them. To jump ahead slightly to your next question, Borges is a big influence, and I’ve always been drawn to mazes and labyrinths of all sorts (the womb is the simple maze we start from, right? Then they get harder from there). The idea, too, that we are laybrinthine to ourselves is also right up my alley. I think my narrators dig with their voices first, if that makes sense. I use voice to find out the dimensions and overhangs, where things echo and where they carry, and then I follow them there, usually gropingly and in the dark.

Mb: These stories remind me of the best of Borges and Nabokov. Who are your biggest influences and what made you want to become a writer?

TH: First off: holy crap and thank you. Either of those guys would be much more articulate, of course. But certainly those are influences. There are a multitude of others, too. In addition to the above writers that I’ve already mentioned, Norman Rush has been huge for me. I’m actually finishing interviewing him as I type this—the interview is set to go up on the Tin House blog, so he’s been very much on my mind. Certainly Calvino. David Huddle, one of my teachers, Cormac McCarthy, Franzen for a time, Guy Davenport, Roth, Wallace, TC. Boyle, Andrea Barrett, Renata Adler, Charlotte Bacon. Paul West, Primo Levi, George Konrad, Marilyn Bowering, Cynthia Ozick. I read the Best American Short Stories and Conjunctions somewhat religiously for years, so there’s no doubt that’s amounted to a big influence, and one of the biggest things that made me want to be a writer. Music is a tremendous influence—if you listen to enough Meat Puppets, Sonic Youth, Conlon Nancarrow, Cecil Taylor, and Hüsker Dü, you’ll get a sense of what I’m trying to do. It’s still a bit of a mystery to me why I want to become a writer—how every day in some fashion, often tiny, sometimes neck and neck with the squirm of living organisms, and sometimes by looking benign next to a lot of other awful shit in the world, literature reaffirms itself, for me, as damned near the best thing we’ve got going.

Mb: There’s an uncanny sort of seething beneath many of these stories. Many of them are kind of balancing on the precipice of reality and unreality. What is the relationship between the real and unreal in art?

TH: Since I believe that we dwell as much in possibility as actuality, I want to think that reality and unreality are not opposites, but rather there are many possible realities that are vying with one another at all times. What makes some of them more interesting than others—therein lies the rub. Since so-called reality reveals itself to be exceedingly strange when we look at it with any degree of care, then it follows that the precipice is not so much between reality and unreality, the precipice is reality. All it takes is looking hard, which science does, and which, in another fashion, art does. I suppose that’s where the uncanniness comes into play. There is no unreal in art, only uninteresting, and usually that can be remedied with a few pen strokes, a brisk walk, the right coffee, or through leaps of learning and unlearning, along with the shock therapy of redoubled curiosity.

Read more from / about Tim Horvath here. Buy a copy of Understories here.

Edward J. Rathke is the author of several books, one of them published [Ash Cinema, KUBOA Press 2012], two more coming out soon, as well as various short stories online and in print. He writes criticism and cultural essays for Manarchy Magazine and regularly contributes to The Lit Pub where he also edits. More of his life and words may be found at edwardjrathke.com.