Reviewed by Robert Long Foreman

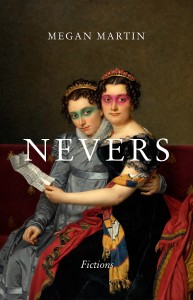

Nevers, Megan Martin

Caketrain Press

ISBN-13: 978-0988891579

$9.00, 114 pages

The short stories collected in Megan Martin’s Nevers do not seem to want to be short stories. They are probably best called something else; fittingly, the cover announces them as “Fictions,” of which there are forty-seven. Written mostly in the first person, they average about two pages in length, none of them running longer than three pages. And this is a remarkable book for, among other things, the way it interrogates the act and the process of storytelling even as it tells stories.

“And What Is Wrong with Spells?” begins, for example, “Wow do I fucking hate doctors! They are the worst people alive.” The narrator airs some grievances, but by the time we reach paragraph three the piece has sidestepped itself, declaring, “Okay, the real story is about a woman who is terrified by a dark mass she is certain is growing deep inside her.” And from there, we are taken to a medical exam, where the woman we have been introduced to can hardly keep herself from telling a story of her own to the doctor, until we are told that “Several weeks later, the story [the one we’re reading] refuses to end,” and we conclude with the regret that “the story is so wanting for human connection.” The piece is something like a tightly coiled wire that unspools before us as we read. It is a story within a story that is more than willing to criticize itself.

Nevers is a book that knows you’re reading it, and it will not hesitate to address this fact as you read. “It should be clear by this point in the book,” Martin admits at about its halfway mark, “how I am the most inconsistent and unreliable thing.” It is an utterly Montaignean admission of one of the predominating tendencies of the short fiction collected here. It readily makes leaps we don’t see coming, darting between ideas and narratives, and I had the frequent impression that, while these are “Fictions,” which implies that Nevers is narrated by fictional characters, we hear Martin’s voice intermittently throughout it.

“I am sick and tired of developing characters,” she writes. “I am the cheapest prostitute ever, forever peddling rogue, diseased syllables in the alleyways, lifting my leg to piss a fourteen-page fire.” It is a statement that represents well the charismatically begrudging voice we hear in much of the book. And it is a brash declaration that would not be half as winning as it is if Martin did not add, in a concluding paragraph, “It is really hard to get up in the morning, it should be needless to say.” It is one thing to second-guess the impulse to invent fictions, another to then question that impulse to second-guess, or at least acknowledge the exhaustion that comes with such circumspection. This is a book that cannot sit still, and it persistently doubts and questions itself, unable to shake the frustrations it meets on the way to narrative.

The momentum that Martin has harnessed in her short fiction, and its accompanying hyperbole, are put to great use, with lines such as, “For me, writing feels like simultaneously stabbing and being stabbed.” It captures perfectly the frequent plight of any writer for whom writing often poses a problem. Writers—Martin included—are frequent targets of the book’s vitriol. “Forever Bloodcloud” concerns another, politer writer, whose “poems do not believe in grease fires or broken glass or in spilling hot java on somebody’s groin on purpose.” “I would spill hot lava on my own groin underwater if I could,” the narrator declares, and this was one instance where the hyperbole went where I would rather not be taken. It is invoked here for the sake of contrasting Nevers with other, more reserved work that refuses to get its hands dirty. “What a positive outlook and genteel-yet-fuckable ass,” Martin writes of this other writer, “but I’ll warn you: do not mistake me for her on the street.” Martin is doing more with this than simply being negative about someone else’s writing; there is value in identifying what one does not want one’s work to be, or to be confused with. But Nevers seems already to accomplish that, simply by being so unmistakably what it is, and so this self-declaration comes across as redundant.

These fictions are at their best when they are on the verge of unsettling us, or are rushing headlong into unsettling us, such as when the narrator in “Beside These Detestable Cheeses” is eating pieces of cheese, and tells us, “Even the super blue ones I despised smiled inside me like a pregnancy.” A sentence like that, with a simile that pounces like that one does, is an accomplishment. There are many such moments in evidence in Nevers.

All writing is a struggle, but finished work rarely acknowledges that strife outright. Imbued with a consistently self-conscious and well-earned world-weariness, the impression one gets is that the fictions collected here had to fight to become what they are. They bear their bruises proudly, and they are well worth our attention.

Robert Long Foreman is from Wheeling, West Virginia. His fiction and nonfiction have appeared most recently in Hobart, Fourth Genre, the 2014 Pushcart Anthology, and Another Chicago Magazine. He teaches creative writing and literature at Rhode Island College, and you can find him on Twitter here.