Reviewed by Michelle Newby

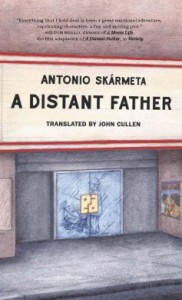

A Distant Father, Antonio Skármeta, Translated from the Spanish by John Cullen

Other Press

ISBN: 978-1-59051-625-6

$15.95, 101 pages

A Distant Father by Antonio Skármeta is a spare but arresting novella. A master at work, Skármeta proves that it isn’t necessary to painstakingly draw every individual brick in a wall; a few suggestive brushstrokes, mere scaffolding, can deliver full impact.

The author of Il Postino: The Postman, which inspired the Academy Award-winning film of the same name, Skármeta won the Premio Iberoamericano Planeta Casa de América de Narrativa for his novel The Days of the Rainbow. He was awarded Chile’s National Literature Prize earlier this year. In his latest, Skármeta begins casting his spell immediately, on page one:

“My life is made up of rustic elements, rural things: the dying wail of the local train, winter apples, the moisture on lemons touched by early morning frost, the patient spider in a shadowy corner of my room, the breeze that moves my curtains.”

Jacques is a young teacher in the tiny, provincial village of Contulmo, Chile, who also translates works in French for newspapers while dreaming of one day publishing his own poetry. On the day he arrived home a year ago with his teaching degree in hand, he stepped off the train onto the platform in time for his father to kiss him and climb onto that same train and disappear. Jacques’s description of the effect his father’s departure has on his mother is a perfect example of those few, deceptively simple brushstrokes evoking depths of feeling: “When Dad went away, my mother was suddenly extinguished, like a candle blown out by a gust of frosty wind.”

In keeping with Skármeta’s framework style, humor occurs in discrete pockets; it insinuates, never shouts, as when Jacques explains why his second job is necessary: “A nurse in the hospital initiated me into the vice of smoking cheap cigarettes, and in order to support this habit—which gave me bronchitis—I’ve had to find a second job.” And when he speaks of his attempts to have his own poems published: “Sometimes I include an original poem of my own in the envelope with my translations and ask the editor to consider publishing it. His response, though negative, is courteous, given that he never rejects my poems and never prints them either.”

Eloquent of loss and bewilderment, Skármeta’s sentences are succinct while simultaneously offering pleasant surprises in their keen observations. These astute sentences regularly bring you up short, packing an unexpected wallop: “Everybody around here is very respectable, and I have no doubt that Teresa and Elena come from a good family, but every time they go to Santiago, they buy dresses with plunging necklines and tight jeans that cling to their hips and squeeze the air out of my lungs.”

Jacques’s floundering attempts to become his own man, without the guidance of his father, lead him into questionable alliances and situations, liaisons that, while not necessarily dangerous, do threaten to expose secrets that are held close by every small town. In the end, Jacques asserts himself, instead of letting events control him, and engineers a generous and loving orchestration of his own.

Michelle Newby, wandering Texan and recovering hedge funds paralegal, has been blogging and reviewing at www.texasbooklover.com since 2010. Her reviews regularly appear in Monkeybicycle and are forthcoming in Prime Number Magazine, the Concho River Review, and World Literature Today. She is at work on her first collection of short fiction. Follow her on Twitter at @TXBookLover.