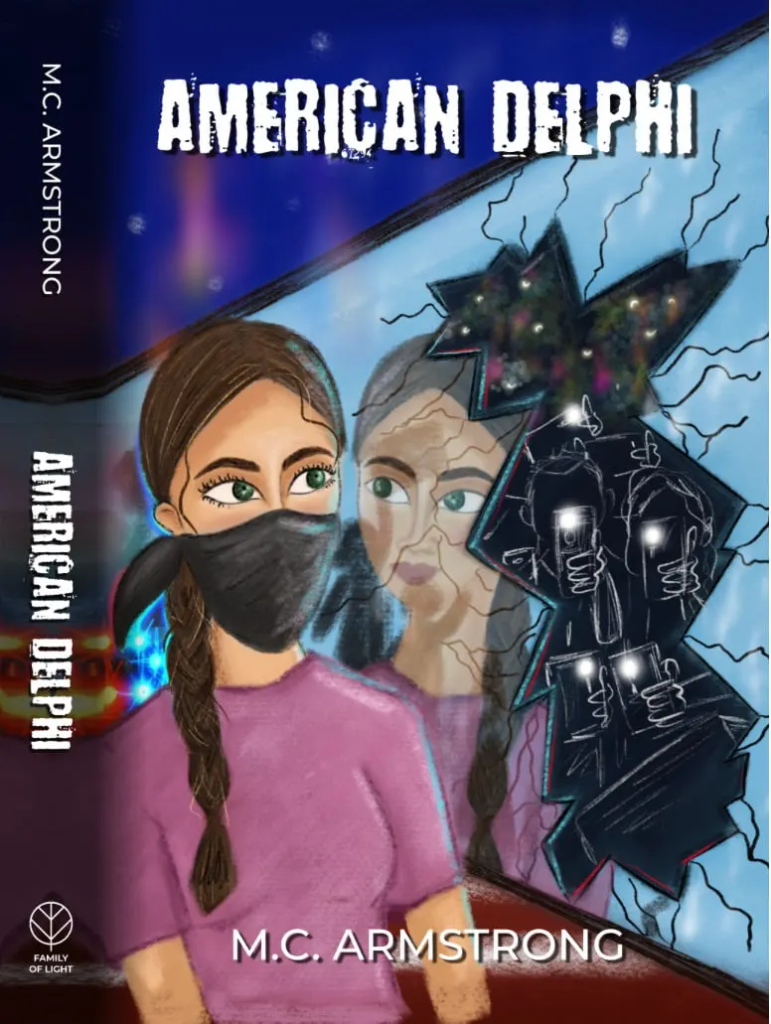

Welcome to another installment of If My Book, the Monkeybicycle feature in which authors compare their recently released books to weird things. This week M.C. Armstrong writes about American Delphi, his debut novel published by MilSpeak Books.

If my book were a muse, her name would be Hannah. I began work on American Delphi in March of 2020, knowing I knew nothing about the new pandemic. But I also felt that whatever was spreading was history and I wanted to capture it. At that time, I was a grad student, a teacher and a musician. My brilliant and adventurous niece, Hannah Armstrong, was seventeen and was about to be taken out of her high school classrooms and sent into isolation. In that sense, Hannah and her “Uncle Monkey” were suddenly alone together, both of us stripped of our peers, banished to Zoom rooms and all the new rituals of the virus: masking, livestreams, virtual hugs and the rigorous and repetitive scrubbing and studying of our bodies. Sitting in my apartment, thinking of Hannah, knowing I knew nothing about the multitudinous forces behind the mass graves and the global panic, I started to compose fictional journal entries from a character named Zora Box.

When I was in high school, I read The Diary of a Young Girl, otherwise known as The Diary of Anne Frank. During the early years of the Nazi occupation, Frank received a notebook for her thirteenth birthday. At the beginning of American Delphi, my fifteen-year-old character receives the same gift from her mother. Why might a parent give a child a diary in the middle of a crisis? Well, one thing I learned as a grad student in literature studying America’s post-9/11 soldier-writers is that, not surprisingly, writing helps people deal with trauma. Every day during the pandemic, when I would wake up, I would sit down and imagine myself as my niece in this post-war America that wasn’t really post-war at all. I would imagine Hannah slash Zora standing at windows and behind screens, observing the body counts and the riots and then observing her reflections in the hall of mirrors we call social media.

To be sure, I didn’t know much more than Hannah about the science behind this rapidly mutating virus from China, but I did know, as a writer, that I wanted a character who wanted to know the truth and wanted to change. People my age don’t tend to have the same neuroplasticity as young adults. If I’m honest, the pandemic made me incredibly sick of the man in the mirror and all the recent characters I’d been generating who seemed so much like me. I needed to be someone else for a change, and maybe I wanted a character who wanted that same thing. Perhaps this goes a long way towards explaining why Young Adult is so popular these days. Not only do readers seem hungry to see change on the page, but maybe we, the writers, enact that hope when we simulate that change—that reach. Maybe when we expand our empathy through the otherness of character, it’s like a vaccine against solipsism, a tiny stab at embracing another life.

Do you need more empathy in your life? Has this pandemic changed you? Is the virus the cure? Did we witness the inception of a totalitarian regime and a conflict worthy of all the George Orwell references Hannah and I both saw circulating on Twitter during the early days of COVID-19? These are interesting questions for me, but what seemed more important at the beginning of American Delphi was getting Zora’s voice right. So, I would send early chapters to Hannah and she would tell me things. We talked about racism, white feminism, police brutality and wokeness. She told me to say, “muffin tops” instead of “front butt.” She told me about “dead names.” We held debates about Tulsi Gabbard. She encouraged me to cut my use of the word “whatever” in half and then in half again. She knew I was writing a novel and she didn’t want to be a caricature. She wanted to discover a character.

Maybe I need to be totally honest here. Zora is not just Hannah. There are two spirits dueling in the Delphi trilogy. If my book were a muse, perhaps the better way to put it would be Zora Box is a Janus of Hannah and my father’s mother, Zora Brooks. The Janus was the Roman God of beginnings, characterized by a double-faced figure. I knew what I wanted when I chose the name Zora. I wanted a character who came from both the living and the dead. Like a father who names his son after himself, I wanted my child to have a history—some kind of compass. How, in the world of YA does one strike a balance between the immediacy of the teen POV and the wisdom some readers seek in the journey of a book? My grandmother, Zora, came of age during World War II and was the wife of one of the engineers on the Manhattan Project. My grandfather helped design the atomic bomb. Zora Box, on the other hand, is the daughter of an Iraq War veteran who committed suicide, or so Zora grows up believing until one summer when a protest movement arrives in her town and a stranger suggests otherwise. Both Zoras grow up surrounded by the white noise of a country in a state of permanent war. Both Zoras, like Hannah, live in the shadow of war—the wars of the past and the wars to come.

What will they do with their lives—this niece of mine and her literary cousin? Hannah could hear the pandemic chants about police brutality here at home, but what about that practice my Iraqi-American friend calls “foreign policing,” or police brutality abroad? How does one speak up against the white noise of the American war machine and the narrative police? One thing I knew at the beginning of Delphi was that Zora Brooks, my grandmother, was the first woman my mother had ever heard use the term “military-industrial-complex.” Many Americans know about the famous men—like JFK, RFK and MLK—who challenged American militarism, but what about the stories of the challengers who happened to be women? My mother admired my grandmother for being one of those pioneers who dared question the world that gave us the atomic bomb, Vietnam and the permanent war economy. As I began to imagine Zora Box, I wanted to give her a name that was laced with that spirit, sure as my grandmother’s blood laced the DNA of Hannah. I never really got to know the Zora Brooks who once hitchhiked with my mother and was a painter and studied Edgar Cayce and The Rubaiyat of Omar Khayyam. The Zora I knew as a child was a hoarse and remote woman who smoked Virginia Slims and was fading away with Alzheimer’s during the administration of George Bush the first. The Zora I wanted to give to the world was, thus, torn between worlds. She sneaks out one night and sees an older girl smoking a cigarette under the moon. She feels a crave. Why, when you know something can kill you, do you beg for it? Why, when America is burning on TV, can you just not sit quietly in your room? Why, Z, won’t you just let the world burn?

M.C. Armstrong is the author of a memoir, The Mysteries of Haditha (Potomac Books), which The Brooklyn Rail called one of the Best Books of 2020. Armstrong, who grew up in Winchester, Virginia, embedded with Joint Special Operations Forces in Al Anbar Province, Iraq, in 2008 and published extensively on the Iraq war through The Winchester Star. The winner of a Pushcart Prize, his fiction and nonfiction have appeared in Esquire, The Missouri Review, The Gettysburg Review, Mayday, Monkeybicycle, Wrath-bearing Tree, Epiphany, War, Literature, and the Arts, The Literary Review, and other journals and anthologies. He teaches writing at Guilford College and is the guitarist and lead singer-songwriter for Viva la Muerte, an original rock and roll band. Follow him on Twitter at @mcarmystrong.