Reviewed by Robert Long Foreman

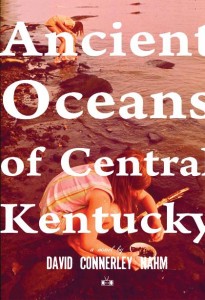

Ancient Oceans of Central Kentucky, David Connerley Nahm

Two Dollar Radio

ISBN-13: 978-1937512200

$16.00, 222 pages

Reading Ancient Oceans of Central Kentucky, the first novel by David Connerly Nahm, is something like reading The Orchard Keeper, the first novel by Cormac McCarthy. The novels are paced at the same slow rate, and, among other things, both rely heavily on their sentences—which all novels do, of course, but perhaps not as much as or quite like these two do; in Ancient Oceans, one has to really look to find more than two purely utilitarian sentences that appear in a row, and throughout the novel are lines that Nahm has apparently worked and worked until they not only serve their purposes but are things of some beauty unto themselves.

The novel concerns Leah, a grown woman who is shown living out her daily life, while we are also treated to glimpses of her childhood, part of which was spent with a younger brother who walked out of their house one night and disappeared, never to be found. As an adult, Leah runs a shelter for victims of domestic violence. She is haunted, in the present day—something that comes out mostly through the florid language that Nahm layers over her; it is the cadence of his writing, more than anything else, that creates the impression that something drags behind Leah wherever she goes.

“Listen,” writes Nahm, “The rooms are cool. Moss reminds her of home. A gale of smoke. They pushed up the nails and her heart stopped.” The impression created by these images is unmistakable, but not easy to describe in plain language—a sign of lyrical writing done well. And lyrical writing done well is necessary to a novel such as this one, which is less concerned with propelling its reader forward through a narrative than it is with sustaining our attention on something that moves in slow motion. Reading Ancient Oceans is something like walking at the bottom of a swimming pool; we do not get far, distance-wise, but the motion itself is, on the whole, satisfyingly dream-like.

As much as I admire the way in which Nahm creates the effects that he does through his mastery of the sentence, I was frustrated with Ancient Oceans on the same grounds on which I was piqued when reading The Orchard Keeper. A great sentence is a thing I admire, but I want it to serve a purpose, and when I encounter many sentences in a short space that look impressive but don’t seem to do enough, I realize how short my patience is for such things. “An old picture of two children, brother and sister,” writes Nahm,

in church clothes standing in front of a fire hydrant, his hair bleached blond and nose sunburned and her arms around his shoulders and her face turned up, mouth open in song, eyes closed, arm out and palm up, cupping pools of sunlight and the boy looking directly at the camera, eyes small and black and wet, mouth set, small and angry.

This comes at a moment when one character is looking for a photograph but can’t find the one she is looking for and sees this one instead, then turns away from it and moves on. There could be something I am missing—there is probably something I am missing—but if attention like this is to be lavished on an image, I want to know why I am being asked, as a reader, to dwell on it; the sheer beauty of its description isn’t quite enough. To offer a counterexample, at another stage in the book,

Even the plants, still and detached, made noises: slim rustles and whistles, dry cracks and moans. All a spray of color and scent, sound and warmth rising in tired waves over and over, never ending, never dying, only growing and churning itself back into growth, churning back on the small farmhouse that sat at its center. All of creation fading into one indistinct, luminous mass and she hated everything about it.

It is the “she hated everything about it” that gives this long sentence a kind of punchline, gathering the first 63 of the words in it and tossing them in a certain direction. And it is this sort of note that helps to keep Ancient Oceans from reading like the novel equivalent of an extended drum solo, something that demonstrates technical mastery but is also, after about a minute, boring.

In a recent conversation about Jayne Anne Phillips’s short story “Bluegill,” I said, offhand, that it would be hard to take the intensity of that story, the magmatic lyricism of Phillips’s diction and syntax, and sustain it for an entire novel, noting that even in Phillips’s own novels the prose ultimately grows more concerned with pressing the narrative forward than with overwhelming us with the sheer force of language. Days later, turning again to Ancient Oceans in order to write this review, I realize that what Nahm has accomplished here is having written a novel that chooses to overwhelm in this way and persist for its duration. With that approach, it loses what appeals in many novels—the sheer momentum of storytelling—but becomes, in the process, something all its own.

Robert Long Foreman is from Wheeling, West Virginia. His fiction and nonfiction have appeared most recently in Hobart, Fourth Genre, the 2014 Pushcart Anthology, and Another Chicago Magazine. He teaches creative writing and literature at Rhode Island College, and you can find him on Twitter @RobertLong4man.