Welcome to another installment of If My Book, the Monkeybicycle feature in which authors shed light on their recently released books by comparing them to weird things. This week Wendy J. Fox writes about her debut novel, The Pull of It, out now from Underground Voices.

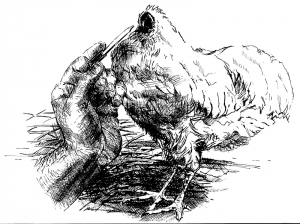

If The Pull of It were a job, it would be your summer in the fruit sheds. You are young in a small town, living among miles of cultivated trees, and you are sorting cherries for so many days that when you close your eyes you still see the belt going past, loaded with little orbs—and when you dream, bone-tired from sitting on the hard plastic seats where you separate the fruit by size (the largest goes to an upper belt you can only feel, and the smaller fruit to a belt below, and the bad fruit down the cull shoot off to be made into juice), the line is there, with you, rolling and rolling.

You recognize the order in this kind of work, but you are also sixteen and your fingers smell like bleach, and you are working six days a week, ten to twelve hours a day. The harvest is bountiful. The belt does not tire. Your shoulders hurt, your ass hurts.

They call it a “shed,” but it’s not someone’s backyard tool storage. There are acres of concrete fitted with loading docks and shipping bays. Men on forklifts who take the processed fruit to cold storage, the room set at 30 degrees, just above the freezing point of the fruit’s flesh. There are boys who unload the tucks from the orchards, tipping the steaming bins into chilled water laced with chlorine. There are workers who are back for another season—a third, a fifth, a twentieth.

And you. You sort Bings for so long that the entire world seems made of deep purple, so when the line changes, the empty belt is blinding white. Then, the Rainiers come and they’re still so bright, flashes of pink and cream.

You chat with people, you sing the song “American Pie” to yourself. You know all the words and if you run through the verses four times, an hour has passed.

Yes, you think, the levy is very, very dry.

You distract yourself with what’s beyond the shed, the orchards, the lake. The lacework of rivers tangling through the small towns.

No one made you take this job, you and your best friend both signed up. You don’t have children. You have a social security number. You have an old car your parents helped you buy. You have never been to jail. You are not addicted to drugs nor alcohol. You are just trying to make some money, and the money, as small as it is, is a way out. You know that. You can’t quite figure exactly how you are going to leave, so the money is the piece that you focus on. The cherries mean you have the thrill of a paycheck that is easy to save, because you have no time to spend.

You show up every morning, you take your scheduled breaks, your thirty-minute lunch. When you leave for the day, the air outside the shed is clear and dry, and the heat of July is shimmering off of the dirt parking lot.

Already, you know you won’t be back for a second season, and you won’t even stay on for the pears, the apples. That’s a start to getting gone.

And, the first time you leave, you don’t go far. You get a better job, a union job, and then you go farther, and farther still. You go so far away from the sheds that the memory of them is almost romantic, so far that you almost miss the measuredness, so far that you almost miss the predictability, so far that you almost miss the way you could feel summer just beyond the concrete walls and the algae smell of the lake and the way being young then was like a promise.

Years later, you’ll be in a grocery store and see that cream and white glint of the Rainiers and you’ll think maybe enough time, a couple decades or so, has passed. You’ll remember how some of the kids would eat so much off the belts they’d spend the rest of their shifts in the bathroom. You’ll take the cherry from the produce display, wipe it on your shirt, and then bite. It’s ripe, and you can tell it’s good, fruit in season.

The other thing you taste is all the hands that got this cherry from harvest to market. You taste the miles, and the line. You taste the fumes from the forklift being refueled and the paper from your old paycheck. You taste the razor-thin edge between having a few choices and few options. You taste the dust of the parking lot, and you taste the sanitation measures, and when you bite, you bite past the sweet of the meat and all the way into the pit, into the bitter core, but you can’t swallow it, can’t even chew.

Almost.

Wendy J. Fox is the author of the novel The Pull of It (Underground Voices, 2016) and The Seven Stages of Anger and Other Stories (Press 53, 2014). Her fiction, essays, and interviews have appeared in ZYZZYVA, The Tampa Review, The Missouri Review, and The Pinch, among others. Find out more at wendyjfox.com or follow her on Twitter at @wendyjeanfox.