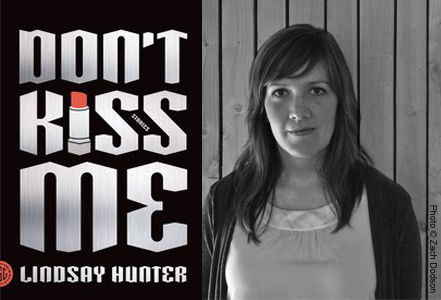

Interview by Edward J. Rathke

Edward J. Rathke: The Next Monsters is a visceral and sometimes gruesome collection. What is the relationship between violence and poetry?

Edward J. Rathke: The Next Monsters is a visceral and sometimes gruesome collection. What is the relationship between violence and poetry?

Julie Doxsee: The day I originally read this question from you I did a reading of The Next Monsters with the word “gruesome” in mind. I claimed to my audience that I would read some of the gruesome pieces, but I couldn’t figure out which pieces were actually gruesome. I read pieces containing imagery of cut-off rabbit ears, Zeus cutting humans in half, and looser impressions of internal/external domestic violence, but I don’t think these pieces are gruesome. Gruesome lives in the mock worlds of horror movies and Halloween gags, but my confrontations with violence are, I guess, more everyday—or are at least treated as everyday subjects. Perhaps this has something to do with how generally nonchalant the world is about violence—I mean that violence has become a behemoth no one knows how to conquer, so people coexist with it—despite certain claims reflecting the opposite. So, the relationship between violence and poetry is really a relationship between violence and the mess of the world. The voice in these poems is the voice of someone who has lived with violence closely and from a distance, of someone who processes it matter-of-factly amid a landscape that offers intermittent escape through humor and delight before the next wave hits. I also believe that language is inherently physical, and therefore has the potential to become violent. I mean words have the potential to carry so much weight that they leave physical imprints, in some way, as they move about the brain and body.

EJR: More than simply violent, there’s also a tenderness at play in these poems, one that surprises you with their juxtaposition to the surreal and grotesque. I feel this captures humanity very well, but in what ways are we monstrous? and how are we not?

JD: When humans become anesthetized to the pain of other people and animals, they develop blind spots in common sense and humanity and the world swirls with monstrousness. Tenderness and monstrousness are often entwined (as in victim and attacker), but those who are anesthetized are immune to tenderness, and those who are anesthetized are also chained to ignorance (the height of monstrousness). Monstrousness of this sort is an epidemic, a sickness, an emergency, but there are no tools large enough to measure it, so the sickness rages on in uncontrollable flares.

Some of the pieces in The Next Monsters come from a very American perspective of defining problems and concocting logical solutions to human pain. But the world is a huge place with devastating problems that Americans in general will never have the proximity or capacity to understand, and therefore will never have the proximity or capacity to solve. A friend told me about a certain island where she lived in the South Pacific. On this island there is no government, and therefore no rape or incest laws. It is common in the culture for male relatives to pass around their own children within the community so that other men may rape them. Pedophiles move to this island and have sleepovers with many children, and it is legal and expected (“Girls on the Run…” is loosely based on this story). These rapists will never be judged in the community, and these children will never know that what they are experiencing is wrong in the eyes of the western world. I hope that anyone who has just read this is horribly sickened to the point of re-thinking his or her entire life, but anyone who has just read this is probably American and somehow involved in the poetry scene. It is not enough to re-think life (at least for me it is not) so poetry has to be some sort of solution for people like us, and when it doesn’t feel like enough, our words become more insistent, more emphatic, more physical, more emergent. What else can we do? We are monstrous when we get comfortable, when we forget, when we do not think and re-think, when we let powerlessness take over as a means of circumventing the insurmountable.

To be thirst and to be scaled down to a beast with insect skin putting your mouth where the dry air meets your expectation with a dark spill of shadows. You search through the room with your hands, press them against the windows to make the water come out. This is your city. They yell through the megaphones while the laundry rots, dishes rot. Your voice is a small cry stuck under the wing of a beetle.

EJR: Your previous collection, Objects for a Fog Death, was more aesthetically beautiful, I think, while this is made up of denser prosepoems that seem less sound oriented. How do you feel your writing is changing as time goes on? And this may be a silly questions but it’s one I find myself asking often: What makes something a prosepoem and not just prose?

EJR: Your previous collection, Objects for a Fog Death, was more aesthetically beautiful, I think, while this is made up of denser prosepoems that seem less sound oriented. How do you feel your writing is changing as time goes on? And this may be a silly questions but it’s one I find myself asking often: What makes something a prosepoem and not just prose?

JD: You are right; Objects is more aesthetically beautiful in some ways. The Next Monsters is a project that wanted to be messy and unruly; it was written while I was adapting to life in Istanbul—one of the most unruly of cities, if only for its immenseness. My previous collections are manicured in a way that felt right at the time, while The Next Monsters is a reflection of something bigger, broader, dirtier, and perhaps more poetically raw. As for the notion of prose poem versus prose, I have to point out that I don’t consider the pieces in The Next Monsters to be “prose poems”; rather, they are prose written by a poet. If a painter places a few pencil sketches alongside other works in a gallery show, is she now a sketcher/painter and not a painter? I identify as a poet because that is the way I am wired, though I do write non-fiction and fiction these days. Another answer might be that the difference between prose poem and prose is that prose is classically associated with narrative, whether it is fiction or non-fiction, and—though I believe there is narrative in everything—the things that people call “prose poems” may be disguising narrative in some way. Then again, there are poems written in verse that are overtly narrative, and fiction pieces that mask narrative (almost) altogether. So, perhaps this question will always yield a post-modern ontology.

A strange sadness forms a cult whose members are upper lip owners. A yawn falls off and forms a Stonehenge at the bottom of the glass.

EJR: I love the imagery and language used throughout The Next Monsters, and feel each section has its own distinct shape, if that makes sense. How important is the sound and shape of a poem to you?

JD: Sound and shape, and the organization of sections in a manuscript are aspects of book-length works that naturally emerge as the project evolves. Each section in The Next Monsters is quite different, though each came from the same poetic demiurge. In terms of the importance of consciously crafting sound and shape, yes, I am definitely in charge of that, but only after the book has taken control and become what it wanted to become. I always think my books are smarter than me; I am quietly satisfied by that notion. Then I start the long period of editing and re-drafting, and realize that we (my book and I) are equally smart and have equal control. Sorry, I didn’t really answer the question…

EJR: This is a bit random, but I saw that you’re from Minneapolis, which is where I’m from, and you currently live abroad. I also lived abroad for a few years and met a surprising amount of Minnesotans all over the world. Do you think there’s something about Minnesota that makes us flee to other countries? Also, how has living abroad influenced your writing?

JD: I am glad you asked a question about Minnesota, because it occurs to me that I regularly romanticize Minnesota—both my former life there and the place as it exists for real. I consider it a place relatively free of human monstrosity; it calms me to think about Minnesota. A few years ago while I was touring for Objects for a Fog Death, I was stuck in a blizzard in New Mexico in the dead of night. Hundreds of cars were planted nose-first in 6-foot snowbanks, and it took me three hours on an off-ramp to get to a nearby gas station in the middle of a profoundly eerie nowhere. The only people in sight were a few drunk truckers in the shop, a few of whom said I could sleep with them (tempting!), until a massive RV with Minnesota plates pulled in. The husband and wife in the RV were Minnesota stereotypes: accents and board games and framed needlepoint hangings. They invited me into the RV for wine and we talked for hours. They offered me the couch, but instead I took a sleeping bag so that I could stay in my car for the night. In the morning they shoveled me out of my car and I was able to drive slowly in their tire tracks until I hit unsnowy roads (count on Minnesotans to handle snowstorms expertly). The whole night was totally unmonsterly after I thought I was going to die. I haven’t encountered too many Minnesotans on other world travels, but I know they are out there being nice and attempting to flee the soul-crushing winter.

As for the question about how living abroad has influenced my writing, I have covered some of that in the above answers. Istanbul in particular is an amazingly influential place to be. The streets radiate with history and magic and soul and questions and complications and kittens and people. It is dirty and unruly and east and west and imperial and poor. My writing is becoming like the city, and I have no choice but to let it.

Edward J. Rathke is the author of several books, one of them published [Ash Cinema, KUBOA Press 2012], two more coming out soon, as well as various short stories online and in print. He writes criticism and cultural essays for Manarchy Magazine and regularly contributes to The Lit Pub where he also edits. More of his life and words may be found at edwardjrathke.com.