Carolyn Oliver

Prudence Mayweather was vomiting when the Hindenburg sailed over our high school. I was holding back her hair. The lavatory windows were open to the mild October morning, and I could hear the swarm of the airship’s engines mellowing the crowd of our classmates and teachers into awestruck silence.

Friday morning’s paper ran a front-page article about the millionaires’ flight over New England, ten hours of cocktails and views of the foliage, accompanied by music played on a specially made lightweight aluminum piano. My parents rushed to catch the bus for work; they read the news at night, if they weren’t too tired. Alone in the apartment, making sure to keep the pages crisp, I studied the hard-faced captain, the jowly industrialists, the menacing, gearlike swastikas on the Hindenburg’s tailfins.

On the walk to school, for the first time in months, I kept checking to be sure nobody was following me.

Classes were unusually quiet as everybody strained to catch the first sounds of the approach beneath the teacher’s lecture. Except me. Instead, I paid exquisite attention to my notes and the soft tap of a pencil against my thigh.

Just as Mr. Harrison began the algebra lesson, Prudence rushed from the room, her face pinched with determination. Mr. Harrison didn’t stop me when I got up to follow, and I confess I took my time in the hallway, enjoying the feeling of being alone and safe. Prudence and I were friends by default, for lack of options. She was pretty, but scrawny in an underfed way that couldn’t be mistaken for elegant slimness, and so shy our classmates assumed she was a snob. A curiosity at best, I was given wide berth thanks to my still-strong accent and my family’s failure to appear in one of the town’s three acceptable churches on Sundays.

Once I reached the bathroom it was hard to hear anything over Prudence’s retching, but as I hurried to catch her hair—stringy, hay-colored, completely unable to hold the wave most of the girls sported—I heard the rush of bodies past the door, gleeful shouting as the teachers tried to maintain order.

“Thank you,” Prudence said, resting for a moment.

“Otto Rogers?” It sounds awful, but I was envious, just a bit. Boys never approached me, except the ones who thought I was desperate.

She nodded but didn’t meet my gaze. “My parents spend Saturday afternoons with my aunt, at the hospital. I stayed home to do schoolwork and . . . Esther, how did you know?”

“He is not teasing me anymore.” As the sound of the zeppelin grew louder, I thought I heard music, the lullaby from Humperdinck’s Hansel and Gretel, which my mother sang to me a long time ago, when we had a house with many rooms and she did not need to work in a factory.

I imagined my small friend humming the same song, swollen-bellied, like the airship. “What will you do?” I asked, as softly as I could.

She sighed, stumbling over to the sink to rinse her mouth, and I wondered if she wanted to be up in the air, where there was nothing for her to fear, with those millionaires who could do as they pleased without permission or censure. But she said, with a smile too grim for her face, “I don’t know. But at least today nobody will remember me running out of class.”

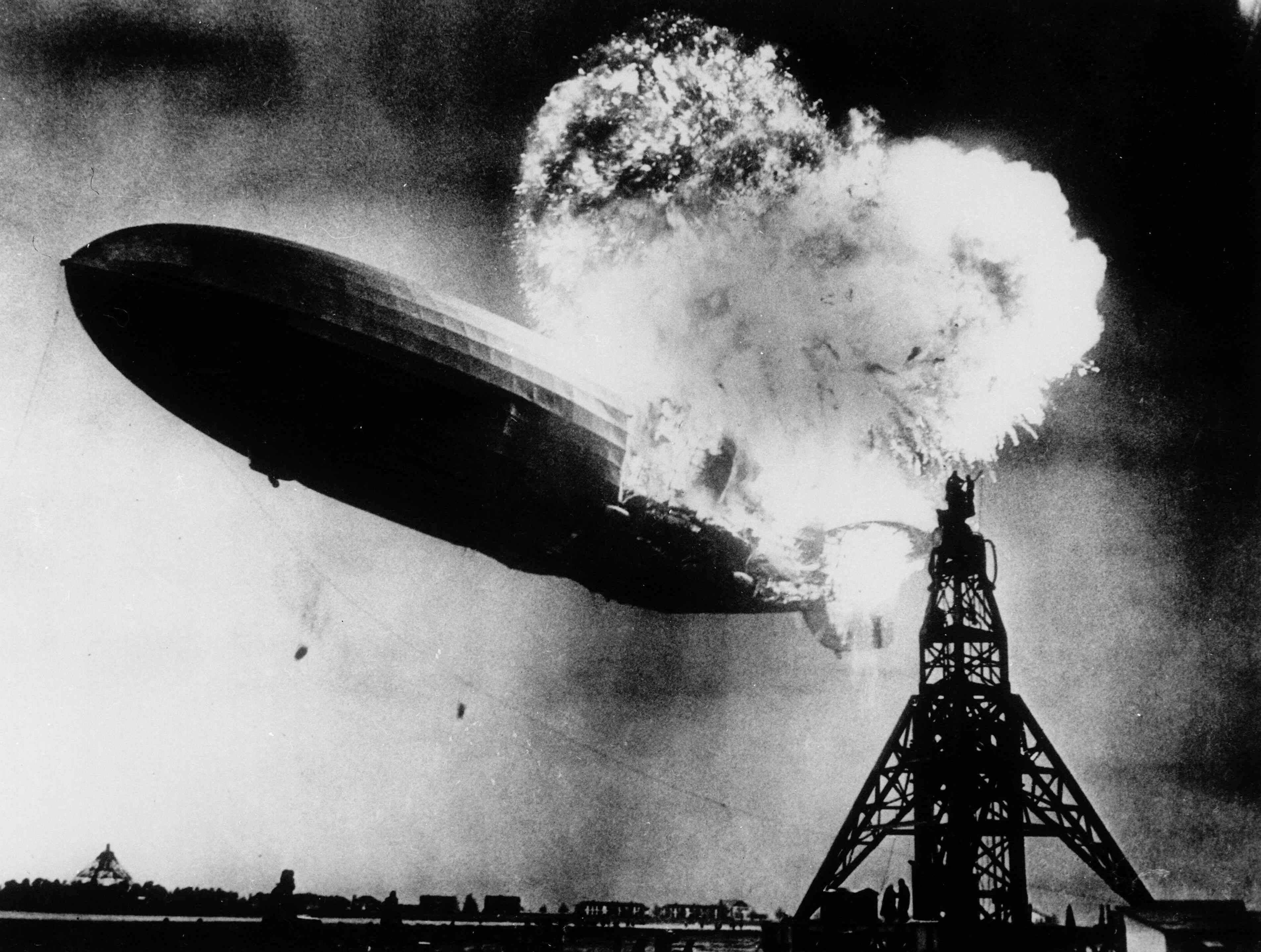

We didn’t see the Hindenburg the next time it flew—without the aluminum piano—over Connecticut, the day it went up in flames. I had the measles, and Prudence Mayweather and her baby were three weeks in the ground.

Carolyn Oliver’s very short prose has appeared or is forthcoming in jmww, Unbroken, Tin House’s Open Bar, CHEAP POP, matchbook, Midway Journal, formercactus, and New Flash Fiction Review. A graduate of The Ohio State University and Boston University, she lives in Massachusetts with her family. Links to more of her writing can be found at carolynoliver.net.