Reviewed by Mike Wood

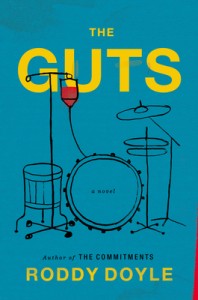

The Guts, Roddy Doyle

The Viking Press

ISBN-13: 978-0670016433

$27.95, 336 pages

I didn’t particularly like Roddy Doyle’s new novel, The Guts, about a man recently diagnosed with colon cancer. The book isn’t consistently funny enough and is too sentimental; and not that I am a particular glutton for punishment—nor do I believe there is no place in the world for novels about cancer that are not unbelievably sad—but I felt that, to its detriment, the book lacked gravitas.

Now, a long time ago, I read and enjoyed what were at the time, I believe, all of Doyle’s books, particularly his first three, collected later as The Barrytown Trilogy. These books also feature Jimmy Rabbitte, the man with colon—or, because he is Irish, bowel—cancer in The Guts—though only to varying degrees: he’s the central figure in The Commitments (1987), in which he forms a soul music band in the fictional area of Dublin which gives the trilogy its name; but is less prominent in its follow-ups, The Snapper (1990) and The Van (1991), which focus on other members of the Rabbitte clan. Anyway, as I say, I enjoyed these books and would read anything by Doyle because of them; but after trying twice and failing to make it through 1999’s A Star Called Henry, I concluded that either my tastes had changed radically regarding what constitutes enjoyable fiction, or Doyle had gotten radically schmaltzy. My suspicion is that Doyle has changed less than me, and that if I reread The Barrytown Trilogy I’d enjoy it less than I did previously. But I’m not sure.

In any case, however, and in case you’re less interested in my self-reflections regarding my relationship with Doyle’s oeuvre and more interested in the specifics of his latest work, I will mention these particulars. The novel begins with Jimmy, aged 47, giving his dad the news about his cancer in a pub. Then, for the next fifty or so pages, he continues to convey this same information to various other characters: his wife, his kids, his siblings, et cetera. By mentioning this repetition I don’t mean to suggest these passages are boring—though they’re not always riveting—but rather to point out what is, far more than cancer, the novel’s central preoccupation: the family.

Like a stereotypically overcrowded Irish household, the book is bursting to the seams with scenes set in the home: in Jimmy’s kitchen, his bedroom, eating dinner with his family, et cetera. In the below, Jimmy, who is undergoing chemotherapy, is eating dinner and talking with his wife (Aoife) and two of his three sons (young Jimmy and Brian), as well as his teenaged daughter (Mahalia), who, like many a fictional teenaged daughter before her, says like a lot and is trying to be a vegetarian, about the dog that has, mysteriously to Jimmy, materialized in their house during his illness.

—So, he said.—The dog.

He put some mince in his mouth.

—Delicious, he said, to Aoife – to all of them.

Young Jimmy thought of something; his head was up from his plate.

—Hey, Dad, he said.—That sounded like you said the dog is delicious.

The laughter filled the place.

—All these years, said Jimmy.—And you never knew what went into shepherd’s pie.

—That’s, like, gross, said Mahalia.

She was eating beans and mashed potato.

—Anyway, said Jimmy.—We’ve a dog. That right, Smoke?

Brian nodded so much his face had problems keeping up.

—Well, said Jimmy.—I want the right to name him.

There was silence, except for the cutlery.

—What’s wrong?

—Nothing.

—Does he have a name already?

—No, said Mahalia.

—Then wha’ then? said Jimmy.—There’s somethin’ wrong. What?

—There’s nothing wrong, said Aoife.

—It’s the way you said it, said Mahalia.

—Said what?

—I want the right to name it.

—How did I say it?

—Like it was your last wish, like, said Mahalia.

Aoife was looking at Mahalia.

—You’re amazing, she said.

—I’m just saying the truth, said Mahalia.

—Yes.

—Did I though? said Jimmy.

A chair scraped, not very dramatically. But Brian was standing, wet-faced, heading for the door to the hall.

—I’ll go after him, said Jimmy.—God, Jesus – I’m sorry.

—Leave him a minute, said Aoife.

—I was joking’, said Jimmy.

—We know.

—I’m sorry.

The self-pity felt a bit like the nausea – but only a bit.

He whispered, to all of them.

—I wanted to call him Chemo.

—Cool.

—Savage.

Jimmy kept whispering.

—But I don’t suppose I can call him that now.

As is the rest of the book, the above is light, occasionally amusing, and nearly all dialogue. Doyle uses few visual descriptions, favoring instead as compliment to his certainly readable dialogue, other auditory details: the family’s laughter, the sound of their cutlery, the chair that scrapes as Brian stands. When Doyle does offer visual cues, these can be succinct and very funny. My favorite involves his description of some of the musicians Jimmy works with, a kind of new-age Celtic outfit called The Bastards of Lir, whose leader is named Ned. Jimmy meets up with them at a large music festival.

The Body and Soul stage, when he found it, was like something from Lord of the Rings. It was in among the trees, in a hollow, a tiny natural amphitheater.

The Bastards of Lir were waiting there.

—Ned.

—Jimmy.

Five men, four ponytails. Three leather waistcoats.

Yet much in the novel rings less true than the above. A loopy, cartoonish subplot involves Jimmy’s son Marvin singing some faux old Irish ballad and pretending, at Jimmy’s request, to be Bulgarian; and another subplot – the details of which I shan’t reveal – that given Jimmy’s feelings for his family I found likewise tough to swallow; though in this I may simply be misreading or simplifying his character. And though not much really happens in this book – there is about as little tension as can exist in a book whose protagonist has a life-threatening illness – Doyle does manage to weave in a few other bits and bobs; sadly, however, the space constraints of this website prevent me from elucidating the entirety of those elements right this second. Similarly, there are many more deficiencies in the text that I just don’t have the space to get into. But, surely, this is all much for the best. In either event and in summation: I don’t recommend that you read The Guts . . . but it’s a pretty quick read. I can understand why, if you really like Doyle, you would. And, if you do, I hope you like it; but if you don’t, don’t say I didn’t warn you.

Mike Wood has a story in the current issue of Driftwood Press.